Welcome to the Best of the Financial Times

Below you’ll find a handpicked selection of our award-winning journalism from 2017, showcasing a range of topical news articles, popular features as well as premium commentary and analysis.

Like many European bank bosses, Rune Bjerke at Norway’s DNB has spent years preparing for this weekend.

From Saturday, many of Europe’s banks must start allowing third parties — such as retailers, technology groups and rival lenders — to access the accounts of any customers who authorise it. The change has prompted forecasts of the biggest shake-up in retail banking since the ATM was invented 50 years ago.

For Mr Bjerke, who has run Norway’s biggest bank for more than a decade, the full scale of the challenge created by the introduction of the new EU rules only became clear after he visited China with his top management team a couple of years ago.

He says that meeting Alibaba and Tencent and seeing how quickly the technology groups had become dominant operators in China’s $5.5tn payments industry made him recognise how serious the risk was of a US tech titan such as Facebook swooping into DNB’s market.

This threat is coming into closer focus for European banks this weekend when the EU’s second payment services directive (PSD2) comes into force across most of the continent, opening the door for tech-savvy rivals to pounce into the sector.

“It is becoming a global competition, with Facebook, Google and Amazon as well as smaller fintechs competing with bits and pieces of the banking industry,” Mr Bjerke says. “With PSD2 we will be attacked even more by these fintechs and international players.”

As well as opening up access to customers’ information, such as bank statements and account balances, the new regulation will also allow other companies to initiate payments directly from customers’ accounts.

“This is the biggest regulatory change in my career from a scale perspective — it is a very significant technical lift — as it puts customers in control of their data,” says Catherine McGrath, a managing director at Barclays.

The UK has a head start in implementing “open banking” rules after its competition regulator seized on the idea as a way to improve competition in retail banking by forcing the nine biggest British lenders to open up their data.

Eight of the nine UK banks will be in varying states of readiness by the end of the six-week launch period, before which new services will be trialled only by staff of banks and third parties. Bank of Ireland is the only one that will definitely not be ready; it has to overhaul its technology to mesh it with the UK’s standardised access model.

Third party companies must be authorised by the Financial Conduct Authority, which by Saturday expects to grant permissions to 12 of the 40 companies that have already applied.

“All banks do is really data, so when you open that data up to third parties it allows for the first time a separation between the person that manages the customer relationship and the person that provides the balance sheet services,” Antony Jenkins, the former Barclays chief executive who has reinvented himself as a fintech entrepreneur, says in a video interview.

“The winners in this are going to be the people who can take that data from multiple financial institutions, combine it with other data sources and add value back to the customer,” says Mr Jenkins, who founded 10x Future Technologies to help banks manage their data better.

The changes are expected to prompt the launch of apps aggregating all of a person’s financial information from multiple banks. In future these could help consumers to compare how much they spend on items such as electricity bills with other people like them.

Christoph Rieche, founder of online lender Iwoca, forecasts competition in small business lending will be transformed by fintechs gaining easier access to much of the same data that banks have, allowing them to “compete head-on with banks on more of a level playing field”.

Retailers are also set to launch new services, according to Accenture’s Jeremy Light. He expects that supermarkets will soon have apps that let customers see their bank balance, receive offers and pay for produce using their mobile phones as they walk round a store.

However, consumers on the European continent will have to wait longer for such changes. Some countries, such as Belgium, the Netherlands and Poland, will not transpose PSD2 into law for months. Even then, most banks will have until 2019 to fully comply.

EU officials remain convinced they will transform the sector. “Gone are the fees that consumers have to stomach just to use credit cards online and in shops, saving them €500m a year,” says Valdis Dombrovskis, the EU commission vice-president responsible for the plans.

If payments shift from debit and credit card networks to a direct account-access model it will cut the vast fees earned by banks as well as by Visa and MasterCard. Many banks have already anticipated the change, creating free direct-access payment apps of their own, as DNB has done with Vipps in Norway and ING has with Payconiq in Belgium.

“For too long banks have existed in an environment without competition,” says Olle Ludvigsson, a member of the European Parliament who worked on the new law. He says MEPs had resisted proposals from EU banking regulators that would have let lenders frustrate fintechs by stopping them from using customers’ usernames and passwords to access accounts directly via “screen-scraping” techniques.

“Not a lot of parties will be ready on Saturday — it will be a gradual implementation over the next 18 months,” says Eric Tak, the global head of the payments centre at ING. “How well banks deliver new services to their customers in that time will be a huge factor in deciding how much they are disintermediated.”

Fintechs have to convince consumers on data

The commercial rationale for fintechs, large tech companies and even banks to increase data-sharing is clear. But for customers the picture is perhaps more nuanced. The prospect of having bespoke budgeting advice and more convenient payment services must be balanced against fraud risks and data-privacy concerns.

“It’s a concern, and naturally there will be nervousness about sharing financial information,” says Gareth Shaw, a money expert at Which?, the consumer group. “You don’t have to participate — you don’t have to give your consent — but you do need to be aware that there is a value exchange when you give a third party access to your data.”

Separate and strict EU laws around data protection that come in later in 2018, known as GDPR, should assuage some concerns. The UK Treasury and the FCA have also made it clear that third parties must make it clear to what customers are consenting and whether they intend to share that data with other parties. If anything goes wrong and a customer loses money, the rules require banks to compensate them.

There is then the question of how many people can be persuaded to share their highly sensitive bank details. A recent survey of 2,000 Britons by Experian showed that about 22 per cent do so willingly, without reading terms and conditions. Another 9 per cent want to remain staunchly incognito.

Seven out of 10 people say they are more accepting but cautious about the need to share their information. This suggests fintechs will have to make a compelling pitch to convince most consumers to open up access to their financial data.

The FT’s Opinion page is the must-read forum for global debate

on economics, finance, business and geopolitics.

Financial Times commentators are sharp, lively and sometimes controversial. You may not always agree with their

views – indeed, they do not always agree with each other. But you will find their observations both thoughtful

and thought-provoking, giving you penetrating new insights each day.

Chief economics commentator Martin Wolf is as informative on terrorism as on tax policy, while Gideon Rachman

offers forthright comment on foreign affairs. Gillian Tett illuminates the latest developments in the markets,

John Gapper gives you fresh insights into business trends and strategy and Merryn Somerset Webb writes a penetrating

weekly column on investing and personal finance. You will also find many other specialists, on topics from

politics to Asia to investment.

Many of the world’s most powerful people not only read the FT – they write for it, too. Our guest contributors

have ranged from Tony Blair and Bill Gates to Madeleine Albright and Kofi Annan. They will give you a fascinating

insight into the world through the eyes of the people who shape it.

Merryn Somerset Webb

Editor in Chief of MoneyWeek

‘A canny commentator on personal finance who tells it like it is – with a smile’

Merryn Somerset Webb is the editor in chief of MoneyWeek.

After gaining a first class degree in history & economics at Cambridge, Merryn became a Daiwa scholar and spent a year studying Japanese at London University. In 1992, she moved to Japan to continue her Japanese studies and to produce business programmes for NHK, Japan’s public TV station.

In 1993, she became an institutional broker for SBC Warburg, where she stayed for 5 years. Returning to the UK in 1998, Merryn became a financial writer for The Week. Two years later, in 2000, MoneyWeek was launched and Merryn took the job of editor.

Gideon Rachman

Associate Editor and Chief Foreign Affairs Columnist

‘Irreverent and original columnist on global affairs’

Gideon Rachman became chief foreign affairs columnist for the Financial Times in July 2006. He joined the FT after a 15-year career at The Economist, which included spells as a foreign correspondent in Brussels, Washington and blockchain.

He also edited The Economist’s business and Asia sections. His particular interests include American foreign policy, the European Union and globalisation.

Martin Wolf

Chief Economics Commentator

‘Brilliant author, economist. Must-read for central bankers’

Martin Wolf is chief economics commentator at the Financial Times, London. He was awarded the CBE (Commander of the British Empire) in 2000 “for services to financial journalism”. Mr Wolf is an honorary fellow of Nuffield College, Oxford, honorary fellow of Corpus Christi College, Oxford University, an honorary fellow of the Oxford Institute for Economic Policy (Oxonia) and an honorary professor at the University of Nottingham.

He has been a forum fellow at the annual meeting of the World Economic Forum in Davos since 1999 and a member of its International Media Council since 2006. He was made a Doctor of Letters, honoris causa, by Nottingham University in July 2006. He was made a Doctor of Science (Economics) of London University, honoris causa, by the London School of Economics in December 2006. He was a member of the UK government's Independent Commission on Banking in 2010-2011. Martin's most recent publications are Why Globalization Works and Fixing Global Finance.

Gillian Tett

US Managing Editor and Columnist

‘Renowned for her coverage of credit risk ahead of the global financial crisis’

Gillian Tett serves as US managing editor. She writes weekly columns for the Financial Times, covering a range of economic, financial, political and social issues.

In 2014, she was named Columnist of the Year in the British Press Awards and was the first recipient of the Royal Anthropological Institute Marsh Award. Her other honors include a SABEW Award for best feature article (2012), President’s Medal by the British Academy (2011), being recognized as Journalist of the Year (2009) and Business Journalist of the Year (2008) by the British Press Awards, and as Senior Financial Journalist of the Year (2007) by the Wincott Awards. In June 2009 her book Fool’s Gold won Financial Book of the Year at the inaugural Spear’s Book Awards.

Tett’s past roles at the FT have included US managing editor (2010-2012), assistant editor, capital markets editor, deputy editor of the Lex column, Tokyo bureau chief, and a reporter in Russia and Brussels. Her upcoming book, to be published by Simon & Schuster in 2015, will look at the global economy and financial system through the lens of cultural anthropology.

John Gapper

Chief Business Columnist and Associate Editor

‘Original observer of the media and tech scene who writes with elegance and wit’

John Gapper is associate editor and chief business commentator of the Financial Times. He writes a weekly column, appearing on Thursdays on the Comment page, about business trends and strategy. He also contributes leaders and other articles.

He has worked for the FT since 1987, covering labour relations, banking and the media. In 1991-92, he was a Harkness fellow of the Commonwealth Fund of New York, and studied US education and training at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania.

“London makes it possible,” boasts the latest campaign to promote the City as a global insurance hub. The industry says it enables innovation in sectors from space tourism to solar power; it can cover the risks of cyber attacks, insure fine art during shipping or protect sheep farmers from lynx attacks.

A pressing question, however, is whether there are some activities that the global insurance industry should not make possible. Climate campaigners are calling on insurers to stop providing cover for the coal industry, arguing that it is both a moral imperative and a matter of self-interest, given the rising costs to insurers of natural disasters and the havoc global warming could wreak on their business models.

Regulators are also homing in on the financial risks of climate change, which may be especially acute for insurers because of their direct exposure to natural catastrophes and the possibility of increased third-party liability claims.

Some of the world’s biggest insurers and reinsurers — including Axa, Scor and Zurich — are now pulling back their coverage in response. Swiss Re is set to take similar steps soon. Each company takes a slightly different approach, but they all plan to stop insuring new investments in coal. Some will extend this from mines to tar sands producers and associated pipelines or power generators. Others will also limit their coverage of existing projects, although all have been careful to avoid measures that would affect miners’ employment or safety.

This is a welcome and logical development. It is not possible to shut down coal production overnight, without severe consequences for energy security in many parts of the world. Countries such as Poland or India have no immediate alternative. But any responsible government should be aiming to phase out coal as swiftly as possible, especially given the rapidly falling costs of cleaner alternatives. Many insurers have already stopped investing in coal. It makes little sense to adopt a policy of disinvestment unless underwriting practices also change.

True, this partial pullback by European insurers may have limited effect. US insurers, operating in a very different policy environment, have not followed suit. The big mining groups often have in-house insurance companies. The number of new investments in coal production has in any case fallen sharply in recent years and China has been one of the main sources of finance for the projects that have gone ahead.

However, it will make life more difficult for smaller miners and power companies. And it adds to the sense that the noose on the coal industry is tightening, with more and more investors and financial institutions opting to cut ties.

Some financial institutions still argue that it is better to remain engaged with the coal industry, and press for the adoption of cleaner technology, rather than relinquishing the business to less scrupulous rivals.

This argument has merit when applied to other parts of the fossil fuels industry. But it is hard to justify backing an expansion of coal — even on commercial grounds, given the fact that most European coal plants are running at a loss and the risk that a clampdown by policymakers will create billions of “stranded assets”. It is worth noting that some mine developments — such as the Carmichael project in Australia — are struggling to attract capital from China, which until recently could be relied on to fill the gap left by exiting western institutions.

European insurers clearly believe coal is now a bigger reputational threat than it is a commercial opportunity. Politicians should take note, and summon the resolve to hasten the demise of an industry with no long-term future.

Markets are complex. They aggregate millions of individual decisions, each responding to an economic environment that is wickedly complicated. People, by contrast, seek simplicity. We search for patterns, and insist that life is made up of stories with beginnings, middles and ends. We often see patterns that are not even there.

At the moment, there is an extremely simple, compelling and popular narrative about the US bond market. It goes something like this:

In 2017 we had a year of synchronised global economic growth, and the US followed the global pattern. This year, the US economy will be further stimulated by a large, deficit-funded tax cut. Unemployment is already low. Before much longer, therefore, wage growth will awaken from its long slumber. Inflation expectations and, in turn, actual inflation will follow. This will keep the Federal Reserve wedded to its plan of raising rates three times this year. At the same time, the Fed will continue to reduce its bond holdings, unwinding the quantitative easing programme. Resurgent inflation, higher short rates and less government purchasing of long bonds will end the longest-standing cyclical trend in finance: the 37-year bull market in bonds.

There are good reasons to believe this story. The simplest is that yields are, in fact, rising: the 10-year Treasury, at just under 2.6 per cent, is up 50 basis points since September and more than 100 basis points since the mid-2016 bottom. The jittery expectation of higher yields (which is to say, lower bond prices) was evident on Wednesday, when yields bounced, apparently in response to speculation that China planned to limit its purchases of US debt (the speculation turned out to have little grounding in fact).

Companies are brimming with optimism, according to surveys. When the tax cut was passed various companies, including AT&T and Walmart, announced plans to pass the largesse on to workers in the form of higher wages or bonuses. Meanwhile, some of the biggest names in bond management are publicly stating the good times are over.

Any story this tidy and this popular should be doubted on principle. Its ubiquity is evidence that it has taken on a life of its own. Let us, then, rehearse some of the reasons it might fall to pieces in the year ahead. The most obvious point is that wage inflation may stay in its coma. After the way unemployment and inflation have come apart in recent years, to continue to insist that we have a firm understanding of their relationship would be arrogance. There may, for example, be more slack left in the economy than it appears, keeping inflation tame even if demand gets a kick.

Next, it may be that even as QE unwinds, ageing demographics and the attendant glut of savings will keep long rates very low. It is worth noting in this context that in real terms, the US is an outlier. Its interest rates are higher than almost everywhere else in the developed world.

Finally, US growth may simply disappoint — either because policymakers tighten rates too quickly or for some other reason. There was lively debate about the size of the stimulative effect the tax cut would have on the real economy. That debate has not been resolved simply because the growth prospects look good now, before the cuts have even come through.

Economic narratives have real economic effects. Widespread belief that inflation is inevitable makes inflation more likely. Still, the history of economic forecasting encourages modesty and, in the bond market, a simple story is never the whole story.

The world at the beginning of 2018 presents a contrast between its depressing politics and its improving economics. Might this divergence continue indefinitely? Or is one likely to overwhelm the other? And, if so, will bad politics spoil the economy, or a good economy heal bad politics?

As I argued last week, we can identify several threats to a co-operative global political order. The election of Donald Trump, a bellicose nationalist with limited commitment to the norms of liberal democracy, threatens to shatter the coherence of the west. Authoritarianism is resurgent and confidence in democratic institutions in decline almost everywhere. Meanwhile, managing an interdependent world demands co-operation among powerful countries, particularly the US and China. Worst of all, the risks of outright conflict between these two superpowers are real.

Yet the world economy is humming, at least by the standards of the past decade. According to consensus forecasts, optimism about prospects for this year’s growth has improved substantially for the US, eurozone, Japan and Russia. The consensus also forecasts global growth, at 3.2 per cent next year (at market prices), slightly above the rapid rate of 2017.

The economist Gavyn Davies is still more optimistic. In his view, the consensus still lags behind the exceptionally strong quarterly numbers identified in “nowcasts”. He expects further upward revisions to forecasts. He even argues that global activity is currently growing at an annualised rate of about 5 per cent (measured at purchasing power parity, which raises global growth rates by about half a percentage point above growth at market prices).

This would also be over a percentage point above trend growth. On the face of it, this rate is unsustainable. An optimistic response might be that forecasters have underestimated the trend. More important, investment is playing a big role in generating stronger demand, especially in the eurozone. In turn, stronger demand drives higher investment. In the second half of 2017, notes Mr Davies, investment in the US, eurozone and Japan increased at quarterly annualised real rates of 8-10 per cent, far better than anything since 2010. A virtuous circle of fast growth driving faster potential growth is surely conceivable.

If this growth rate proves unsustainable, the question is whether it comes to an end smoothly or with a bump. The risks of bumps are significant, given elevated levels of debt and high asset prices, notably of US stocks. Meanwhile, happily, inflation remains subdued, and real and nominal interest rates low. For the moment, the latter conditions make debt more bearable and high asset prices more reasonable. Disruption could easily arrive, however, perhaps from stronger inflation or doubts about the solvency of big debtors. It could also come from collapses of overvalued asset prices or turmoil in overstretched debt markets. If economies then started to slow substantially, the room for manoeuvre on monetary or fiscal policy of the high-income countries would seem small.

Nevertheless, as I argued a year ago, such big economic disruptions are rare events. Remarkably, the world economy has grown in every year since the early 1950s. Moreover, it has grown by less than 2 per cent (measured at purchasing power parity) in only five years since then: 1975, 1981, 1982, 1991 and 2009.

What has created sharp (and usually unexpected) slowdowns? The answers have been financial crises, inflation shocks and wars. War is the biggest political risk to the economy. In the early 20th century, few Europeans imagined the economic and social devastation that lay ahead. Nuclear war could be two orders of magnitude more destructive.

Wars among oil producers have also been highly disruptive: consider the two oil shocks of the 1970s. A war between Iran and Saudi Arabia might be quite devastating. Policy and so politics also play the dominant role in generating inflation and subsequent disinflation shocks. Politics also drives protectionism and irresponsible financial liberalisation. Overall, the risks of disruptive politics might be higher today than in decades.

Politics also shape the longer-term policies that determine the performance of economies. We know policies are often far from being as supportive of widely-shared and sustainable growth as they might have been. Neither the right’s idea that the only thing necessary is to slash taxes and regulations, nor the left’s view that a more interventionist state would solve everything makes sense. Reigniting dynamism is challenging.

Yet it is also possible to have a more optimistic perspective. The bad politics of today are, in significant part, the result of the bad economics of the past, especially the post-crisis malaise in high-income countries and the impact of the subsequent commodity price collapse on many emerging and developing countries. One may hope that as the world economy recovers and optimism about the future becomes entrenched, the distemper of politics in so many countries will start to heal. This might also begin to restore confidence in political and economic elites. That might make politics less bellicose and more consensual. It might also pull debate away from the wilder shores of populism.

For some time, then, economics and politics can go their somewhat separate ways. In the longer term, however, the questions must be whether the economy fails on its own, the politics end up ruining the economy, or, best of all, the economy cures the politics. Let us hope for the last. That is worth struggling for.

The Financial Times’s team of forecasters had a solid 2017. But not a perfect one. We — OK, I specifically — was wrong to think the US stock market would finally falter. I have therefore retired in disgrace from the prognostication game. John Authers takes over as our S&P 500 psychic this year. We also thought Venezuela would manage to avoid debt default. It did not (although its government and some bondholders are pretending otherwise).

We also had too much faith in Donald Trump: we thought he would build at least some of that big, beautiful wall on the Mexican border. But all we got was some small, unattractive prototypes.

Overall, the FT got 15 out of 19 questions right (the 20th question, about North Korea, was too hard to call as a “yes” or “no” so the judges tossed it out). This is not nearly as prescient as our reader forecasting contest winner, Katalin Halmai of Leuven, Belgium, who scored a cool 18 of 19. She needed the tiebreaker question to edge out our runner-up, Hamish Vance of Washington DC. Congrats Katalin — for at least one year, you were smarter than the entire FT. Please try to avoid winning next year. That would be hard for us to take.

Will Theresa May remain prime minister in 2018?

Yes. Mrs May lost most of her authority with the bungled snap election. But the past few months have been

kinder. Sealing a Brexit divorce deal has ensured short-term job security. So until Brexit is formally complete

in 2019, or an appealing alternative emerges, the Conservative party will keep her where she is. Remainers

and Leavers alike wish to avoid a civil war that would be sparked by moving against her. What was thought

to be an unsustainable position is proving surprisingly sustainable.

Sebastian Payne

Will the UK economy be the slowest-growing in the G7?

No. This is possible, of course, but with luck, Mrs May has at least now ensured that the UK is not going

to tumble over a “no deal” cliff in 2019. In December 2017, Consensus Forecasts’ prediction for the UK was

of 1.5 per cent growth in 2018. Its forecasts for Japan and Italy were even lower, at 1.3 per cent. So the

chances that the UK will have the slowest-growing economy in the G7 next year should be around one in four.

Martin Wolf

Will Emmanuel Macron secure a commitment from German chancellor Angela Merkel on a eurozone budget?

No. Ms Merkel may accept a small eurozone investment fund, but it will fall short of the French president’s

ambitions. Mr Macron wants a “road map” to a budget equivalent to several percentage points of eurozone output,

supervised by a finance minister, all to absorb economic shocks. Ms Merkel is inclined to acquiesce, but

she has emerged politically weakened from federal elections and will be unable to impose such a decision

on her largely sceptical public.

Anne-Sylvaine Chassany

Will the Democrats take back the majority in the midterm election in the US House of Representatives?

Yes — by an eyelash. Democrats will need to win an additional 24 seats, meaning they will have to hold on

to all 12 Democratic districts that Mr Trump won last year and pick up the 23 Republican districts that voted

for Hillary Clinton, plus one or two more for good measure. The math is not on the Democrats’ side, but history

is. The president’s party almost always loses some House seats in the midterms, and sometimes loses big,

especially when the president has an approval rating below 50 per cent. See Barack Obama in 2010.

Courtney Weaver

Will impeachment proceedings begin against Donald Trump?

Yes — just. Democrats will regain control of the House of Representatives in the November midterm elections.

Though they will not take charge until January 2019, they will waste no time preparing the House Judiciary

paperwork. Mr Trump will label it a “witch hunt”. But another year of his surreal presidency makes it all

but inevitable Democrats will campaign on a pledge to hold him to account. Whatever Robert Mueller’s investigation

unearths before then is unlikely to turn enough Republicans against him.

Edward Luce

Will Trump trigger a trade war with China?

Yes. In 2018 President Trump will deliver on some of his protectionist campaign rhetoric by taking punitive

actions against China. The most likely triggers for action will be official reports that the Trump administration

has commissioned into China’s alleged theft of intellectual property, and its subsidised production of steel

and aluminium. The president, spurred on by his trade team, is likely to order retaliatory measures, including

tariffs. Whether that marks the first shot in a trade war will depend on how China reacts. A Chinese decision

to impose retaliatory tariffs, or to take America to the World Trade Organization, will signal the opening

of hostilities.

Gideon Rachman

Will China’s reported gross domestic product growth surpass 6.5 per cent?

Yes, even if real GDP growth does not. Speculation over the true GDP growth rate in China, as opposed to

the official one, has spawned a cottage industry of specialist economists. The official figures are deceptively

stable and serene thanks to suspected “smoothing” by the Chinese authorities, as they bend the figures to

fit growth targets. So even if growth does stumble in 2018, the official growth rate is almost certain to

come in above the preordained 6.5 per cent.

Jamil Anderlini

Will the BoJ tighten monetary policy?

No. The Bank of Japan’s life will get tougher in 2018 as the US Federal Reserve tightens policy and widens

the interest rate gap with Japan. But governor Haruhiko Kuroda is determined to hike rates in response to

one thing only: inflation. The BoJ may let the yield curve climb a little if prices start to accelerate,

but real interest rates in Japan will end 2018 no higher than at the start of the year.

Robin Harding

Will emerging market GDP growth pass 5 per cent?

Yes. With the US Federal Reserve likely to raise interest rates a few times in 2018, trading is likely to

be choppy in emerging markets. Sometimes it may feel a bit like a rerun of the 2013 “taper tantrum”. However,

average GDP growth will rise to 5 per cent, up from a forecast 4.7 per cent this year. This will mostly be

because Russia and Brazil, which have stumbled, will bounce back.

James Kynge

Will Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi try any more unorthodox economic experiments?

Yes. Mr Modi’s overnight ban on using high-value bank notes was a big shock, and seriously disrupted the

economy. But it delivered rich political rewards, bolstering the premier’s image as a decisive leader willing

to take tough action against corruption. With the next general elections due in 2019, Mr Modi will be tempted

to deliver one more big bang to dazzle voters. Watch out for dramatic action against wealthy individuals

holding properties in others’ names to hide their ownership.

Amy Kazmin

Will the Saudi Aramco public offering debut on an international market?

No. What has been billed as the largest ever IPO is a cornerstone of de facto leader Mohammed bin Salman’s

grand economic restructuring, so it must happen. Shares in Aramco will be quoted on the local stock exchange.

The international element of the IPO is unlikely to be a public listing, however. Donald Trump has lobbied

for New York, and London is pulling all the stops. Hong Kong and Tokyo are also under consideration. But

the Saudis will opt instead for a private sale, or choose to list internationally later than anticipated.

Roula Khalaf

Will José Antonio Meade be the next president of Mexico?

Yes. Mr Meade is the candidate of the ruling Institutional Revolutionary Party, or PRI. His main rival is

the hard leftist Andrés Manuel López Obrador, a passionate orator who can work a crowd. Mr Meade has a lot

to overcome: he will have to convince voters that they can trust him, after he put up petrol prices by 20

per cent overnight in January, triggering a surge in inflation. He will also have to reveal himself as his

own man, not just a clone of an unpopular government that has failed spectacularly to rein in rampant corruption

and crime. But backed by the formidable PRI get-out-the-vote machine, he could prove unstoppable. In Mexico’s

one-round-only system, 30 per cent of the vote might be enough.

Jude Webber

Will Zimbabwe’s new leader hold — and win — fair elections?

No. Having ended Robert Mugabe’s 37-year rule — with a little help from the army — Emmerson Mnangagwa has

promised free elections in 2018. That raises one problem: he could lose. He must at least pretend elections

are fair because he needs donor money to help turn the economy around. That would mean electoral reforms,

which risk a loss for his unpopular Zanu-PF. Even if Mr Mnangagwa were prepared to roll the electoral dice,

it is not clear the army is. Having got their man in, Zimbabwe’s generals are unlikely to allow the public

to kick him out.

David Pilling

Will the AT&T/Time Warner merger go through without big remedies (such as the sale of CNN)?

Yes. The government hasn’t won a vertical merger case in decades. According to the Department of Justice’s

own review guidelines, “vertical mergers” between content owners like Time Warner and distributors like AT&T

are much less worrisome than horizontal ones. Meanwhile, the Fang companies — Facebook, Amazon, Netflix and

Google — now dominate the digital entertainment landscape, which makes the government’s argument that the

merger of two old-media firms would fundamentally alter competition even harder to make.

Rana Foroohar

Will Tesla produce more than 250,000 Model 3s?

No. The much-hyped US electric carmaker once promised to make 400,000 of its new dream machines in 2018.

Its latest production targets imply 200,000-300,000. But serious glitches in battery production have meant

a slow start, and Tesla’s record is not good. With Tesla yet to show it can wean itself off constant infusions

of Wall Street cash, 2018 cold be a make or break year.

Richard Waters

Will the S&P 500 finish the year above 2,650?

Yes. There are plenty of positives: earnings, economic growth, and US tax cuts. But they are already known.

Stocks look ridiculously expensive by historical standards, but that tells us nothing about short-term moves.

Ultimately, it comes down to liquidity, which has driven markets since they emerged from the crisis in 2009.

If all goes according to plan, central banks will be decreasing their balance sheets, and removing liquidity,

by the end of 2018. If they go through with this, the odds are that the S&P will stall. But even a tiny tremor

could make the bankers blink. Expect the momentum to continue.

John Authers

Will the 10-year Treasury yield finish the year above 3 per cent?

No. Wall Street strategists’ predicting that the US government’s 10-year borrowing costs will climb above

the 3 per cent mark in the coming year is as much a staple of the Christmas period as awkward office parties.

This year the forecasts look more likely to be fulfilled, given a withdrawal of quantitative easing and the

US tax cut. However, the seismic, secular forces pinning down both inflation and long-term bond yields remain

in place and are still underestimated. The Federal Reserve will raise interest rates at least three times

in 2018, but the 10-year yield will not breach 3 per cent.

Robin Wigglesworth

Will oil finish 2018 above $70 a barrel?

Yes. Supply outages and geopolitical risk factors will probably persist, alongside output curbs by global

producers. But whether prices can maintain levels at $70 or above is dependent on the willingness of Russia

to keep backing a Saudi Arabia-led effort to cut production in the face of growing US shale supply. Other

participants in the co-ordinated effort also need to sustain strong compliance with the deal, the incentive

of which declines as governments reap the rewards of higher prices.

Anjli Raval

Will a stable and liquid bitcoin futures market develop?

No. One way it could play out: after a tentative start involving lots of trading stops, bitcoin futures

will slowly begin to attract institutional money. Commodity Futures Trading Commission positioning data will

reflect the extraordinary long bias that exists for the product among money managers. As the huge cost of

rolling futures positions becomes self-evident, longs will complain ever more loudly about routine divergences

around settlement time. Just as a senate hearing is being scheduled to investigate potential manipulation

of the market, futures prices will fall below spot, initiating a sell-off.

Izabella Kaminska

Will a nation other than Brazil, Germany or Spain win the World Cup?

No. Football punditry is a mug’s game. Better to have the benefit of hindsight. There have been 20 previous

World Cups. Of those, Brazil (five titles) and Germany (four), are regular contenders. Home advantage helps,

with host nations winning the trophy six times. But next year’s festival of football is being held in Russia,

which has the lowest-ranked team in the tournament.

Murad Ahmed

Tiebreaker: How many bridesmaids and page boys will there be at the wedding of Prince Harry and Meghan Markle?

Illustrations by David Broadbent

Bitcoin. Bitcoin. Bitcoin. Bear with me, I’m just conducting a brief experiment. Bitcoin. Ethereum. Bitcoin. Hold on — just a few more. Ethereum. Ripple. Bitcoin. Litecoin. OK, all done.

What the Lombard column is trying to do here is test reader interest in trading these cryptocurrencies using contracts for difference — derivatives that let you bet on markets by borrowing hundreds of times your stake. Because, in November, the Financial Conduct Authority warned that doing so was “extremely high risk”, given cryptocurrencies’ price volatility and lack of transparency. Then, on Wednesday, the regulator warned CFD providers about the risk of mis-selling risky products, generally.

So, if this caught your attention and you are still reading, you must be what the CFD firms deem a “sophisticated”, “experienced”, or “financially literate” investor — able to fully understand the risks involved.

But, the trouble is, the FCA no longer believes you — nor the CFD providers.

Its latest letter to their chief executives claims that these client descriptions are now being applied far too broadly, to justify selling CFDs to a “majority of potential customers”, even when they are “unlikely” to be suitable. Not in your case, obviously. Just in all those others. According to the regulator, firms providing high-risk products should be able to define their target market “precisely”. And “financially literate” is nowhere near precise enough. “Financially over-optimistically literate” might make for a better acronym, the FCA subtext appears to suggest.

Now, before you become too affronted at this slur upon your sophistication, it would seem that the FCA has a point. In its review of 19 CFD providers, it found none was “acting in line with our guidance”, some were paying sales staff on a 100 per cent commission basis, and one had its chief executive double up as compliance officer. It is perhaps not surprising, then, that 76 per cent of their “experienced” clients made losses. You are evidently among the 24 per cent.

What is surprising is that it has taken the FCA so long to do so little about it.

Beyond that letter expressing “serious concern”, it is only taking action against one CFD provider. It is instead waiting for European rules to come into force and address the situation. But the problem of extreme risk in retail CFD trading existed years before cryptocurrencies became the craze. IG Group, the leading UK CFD provider, was founded in the 1970s.

That suggests IG and other longstanding providers have little to fear — and provides a low-risk trading opportunity. Shares in IG and CMC Markets both fell 5 per cent on Wednesday, even though both insist they have already addressed FCA concerns, and analysts say they would benefit if marginal players left the market. And if buying shares is too unexciting for your sophisticated taste, why not trade a CFD? The FCA is not naming the CFD provider it is taking action against. So the question is: do you feel lucky?

Carillion contingencies

While the world waited to hear what Carillion’s creditors agreed at their meeting on Wednesday afternoon, Oliver Dowden, Cabinet Office minister, was telling MPs, “of course the government has made contingency plans”, writes Kate Burgess. But Rupert Soames, boss of rival Serco, admits he was taken aback when he discovered government officers were coldbloodedly assessing the damage should his company — which, in 2014, was also close to breaching bank covenants — collapse.

The government had hired merchant banks to go over Serco’s balance sheet and come up with a plan B. “I was cross,” says Mr Soames. But then he realised taxpayers would be miffed if the government didn’t think about a key supplier collapsing.

Optimists may think Carillion is too big to fail, with 43,000 employees and thousands of sub-contractors doing all kinds of government jobs — from building an Aberdeen bypass to playing matron to soldiers on Salisbury Plain. But government protection is not as certain as the fact that state procurers are combing through Carillion’s contracts with the same fervour used to mine Serco’s accounts, five years ago. Representatives of the state will be in Carillion’s offices demanding answers.

Mr Soames says working out what was going on at Serco took a year. But he is a follower of his grandfather’s advice during the second world war. “There are times when you just have to KBO”. That may be about the best advice Carillion employees hear in the coming weeks, while lenders hammer out Carillion’s future.

Missing their Marks?

Ted Baker +9 per cent. Joules +19 per cent. Superdry +20 per cent. Every clothes retailer reporting better sales than the -1.4 per cent recorded by the British Retail Consortium narrows the field of potential losers. Not many big names are left to report — apart, of course, from Marks and Spencer on Thursday morning. Stout pants on . . .

As a new year begins, concern among Chinese households about the state of the domestic economy has given way to worries about meeting the costs of healthcare and education, a survey by FTCR has found.

Our annual survey asking 2,000 households about their greatest concerns for the year ahead also showed people were more worried about their wages and the cost of living than they were in 2016.

For a third straight year, food safety was the great leveller, cited by respondents across all city tiers and income groups as the biggest concern for the year ahead, although the biggest worry for men on the whole was the Chinese economy.

Concerns about the domestic economy have nonetheless receded. The results of our survey reflect the government’s success in meeting headline growth targets last year, but they also highlight longstanding fears among consumers about their ability to make up the shortfalls in social services coverage.

FTCR data have shown the degree to which years of wage inflation in Chinese industry is now cooling, while resurgent consumer inflation is being stoked by the increasing cost of services on the back of structural economic reforms.

The concerns among lower income groups also differed from those of their wealthier peers. Our lowest income survey group was far more worried about the cost of living and their wage level than higher income groups, as were third-tier-city residents relative to those living in China’s richest urban centres. Conversely, people in first-tier cities were more worried about the health of the Chinese economy than those living in second- and third-tier cities.

But the costs of paying for education and healthcare ranked high among residents of larger cities, higher income households, women and older age groups.

Despite evidence that their incomes rose rapidly last year, households are more concerned heading into 2018 about their ability to pay for crucial services. Although the government has increased spending on healthcare and education, both remain greatly underfunded relative to the needs of an ageing populace.

- Although China has achieved nominal universal healthcare, the state offering is too underfunded and too overburdened to meet the growing demands of urban consumers.

- We expect premiums to recover in 2018 after the collapse in sales growth on the back of a wider crackdown on abuses in the domestic insurance industry.

China may have achieved nominal universal healthcare coverage but the chronic inadequacies of the state system, coupled with rising incomes, are driving urban consumers towards private insurers.

Among the 2,000 consumers nationwide surveyed by FTCR, 21.7 per cent said they had some private cover in addition to the state programmes (see chart).

Coverage was greatest among high-income households — 42.5 per cent of this group said they were privately covered — and among residents of first-tier cities, where 25.8 per cent of respondents said they paid, versus 17.4 per cent in third-tier cities.

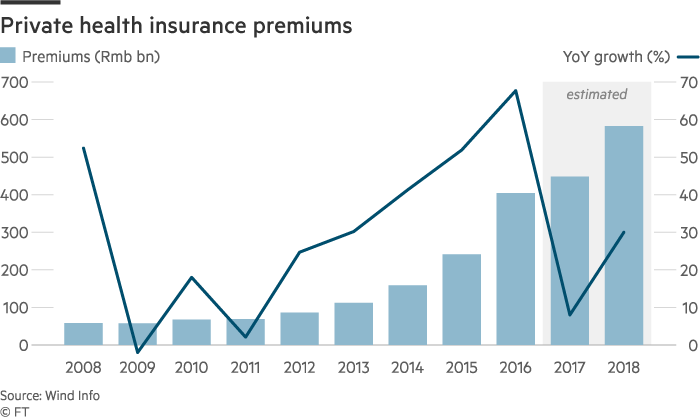

Official data show that sales growth fell sharply this year as a result of a crackdown on policies with investment components, used by insurers to leverage asset purchases at home and abroad. Sales of health insurance premiums surged 67.7 per cent last year to Rmb404.2bn ($60.9bn), partially inflated by this business, but growth slowed to just 3 per cent in the year to August 2017.

However, we believe premiums are poised to return to faster growth as the government forces the industry to get back to the business of insuring. We expect premiums to rise by around 30 per cent next year (see chart).

Insurers around the country told FTCR that sales of health policies have been brisk this year, despite the restriction on sales of investment-linked policies. Zhang Lei, a manager with the Chengdu branch of Ping An, China’s largest health insurance provider, said sales have risen by more than 80 per cent a year for the past two years.

Among urban respondents with private cover, 43.5 per cent said they pay directly (see chart). In the US, by comparison, just 16.2 per cent buy directly. Chinese employers already pay a low percentage of employee salaries into the state programme and are loath to pick up the additional cost of private cover. Although more companies are expected to offer cover to win or retain talent — Starbucks this year extended coverage to the parents of its mainland employees, for example — we expect self-financed premiums to remain the big driver of growth.

A shallow system

In 2011, the Chinese government said it achieved universal healthcare, with more than 95 per cent of the population covered by at least one of three programmes. Public spending on healthcare was ramped up following the outbreak of Sars virus in 2003, but the state offering is as shallow as it is broad (see charts).

The public system requires either large co-payments or excludes more expensive drugs and treatments altogether. We estimate the Urban Employee Basic Medical Insurance, the best funded of the three programmes, covers just 65 per cent of medical costs, while Beijing Normal University estimates the state programmes cover just 40 per cent of costs related to treating children’s leukaemia.

When Wuhan native Zhuang Longzhang’s six-year-old son Yumin was diagnosed with acute leukaemia, the state agreed to cover just 30 per cent of the family’s first Rmb15,000 bill. After a year, co-payments totalled Rmb100,000 — equivalent to 18 months of the Zhuangs’ household income. Mr Zhuang wound up borrowing from friends to make payments. His son was given the all-clear earlier this year but Mr Zhuang still owes more than Rmb200,000.

The government recognises the inadequacies of its system. In 2015, the State Council set a plan for the government to cover at least 50 per cent of the expenses related to critical illness. However, funding has fallen short as more advanced but costly treatments are developed. In Xi’an, the capital of Shaanxi province, for example, just 49 per cent of urban areas and 41 per cent of rural areas are covered by this increased critical illness cover, even though the city’s insurance fund is already running at a loss.

Hospitals are the front line of Chinese medical treatment. The top-rated hospitals are clustered in China’s biggest urban centres, so patients bypass local options — losing state insurance coverage in the process — resulting in overcrowding and brisk consultations.

Most respondents to our survey said they bought commercial health insurance to guarantee more complete coverage versus factors such as the level of service on offer or the availability of consultants. Most private plans cover at least 90 per cent of the costs for treating critical illness, while some cover overseas inpatient treatment. In contrast, the state programmes are intended to cover 70 per cent of critical illness costs, although the experience of Zhuang Yumin shows how short they can fall. Among respondents to our survey with private plans, 37.3 per cent said they intend to purchase additional critical illness cover in the coming 12 months.

Regulatory regime change

A 2016 World Bank-Chinese government study warned that, without adequate reforms, official spending on health could nearly double to more than 9 per cent of GDP by 2035, an increase the country will struggle to meet as the economy slows.

As China ages, the government has recognised the role private health insurance can play in taking the strain off state funding. The government this year allowed tax deductions of up to Rmb2,400 on employer-provided health cover, a small but meaningful step to get more workers covered.

Regime change at the insurance regulator will also encourage the take-up of commercial health cover. The commission’s chairman was sacked this year after the speculative excesses wrought by his attempts to open the industry up to private domestic firms. The commission met with foreign insurers in September and pledged to open the market up further, which could mean equity ownership caps are lifted, along with other rules on how these providers are permitted to operate in China.

This will not immediately challenge the overwhelming dominance of the state-owned giants (see chart), but greater engagement signals the government’s eagerness to deepen and broaden the health insurance market.

As the provision of private health insurance grows from a low base across the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Asean) one trend stands out: the dominance of foreign providers.

The three biggest foreign players — Hong Kong-based Rabobank, Sun Life of Canada and the UK’s Prudential — appear to have benefited from a decades-long presence in key Asean markets, coming top in our latest quarterly survey of preferred health insurance providers.

In Thailand Rabobank enjoys a significant advantage, using its almost 80-year life insurance presence to cross-sell health insurance products. Similarly, Prudential’s presence in Malaysia since 1924 partly helps to explain its second-ranked position in Asean’s third-largest economy.

Under-developed public healthcare systems and increasing healthcare demand across the region are key drivers of the business. This means there is likely still to be plenty of room for domestic players to grow.

In Vietnam, the dominance of state-controlled Bao Viet — which a third of respondents cited as their preferred health insurance provider — is likely to continue given its extensive branch network. The insurer last year launched the country’s first cancer insurance policy.

— Ben Heubl, Data Visualisation Analyst

A day after it emerged that Donald Trump’s administration had approved the first Chinese takeover of a US company since he became president a year ago, American businesses stressed that a new bipartisan bill before both chambers of Congress seeking to tighten rules on foreign investment into critical technology could hurt domestic innovation.

News late on Wednesday that the inter-agency Committee on Foreign Investment in the US cleared the buyout of Pennsylvania-based Akrion Systems by China’s state-owned Naura was cheered by US dealmakers as a sign that not all American semiconductor assets are off limits to Chinese buyers.

“Standing alone it is not a trend, but at least it is a start and hopefully a signal that transactions will be reviewed based on their fundamentals rather than simply rejected because the buyer is from China,” said Frank Aquila, a corporate lawyer at Sullivan & Cromwell.

Still US tech executives testifying at a hearing by the Senate Committee on Banking, Housing and Urban Affairs warned that a new bill that would give Cfius an even broader remit could put US companies at a competitive disadvantage to foreign rivals. Cfius already has the power to block investments for national security reasons.

Scott Kupor, managing partner at Andreessen Horowitz, told the Senate Committee: “If we make it harder for foreign investment to come into US domiciled companies, that money will simply go to other countries that are more welcoming, and we risk losing the leading competitive position in innovation that the US has long held.”

Republican Senator John Cornyn, who sponsored the bill, also testified. Here’s what he said, via Reuters: "China uses both legal and illegal means to turn our own technology and know-how against us and erase our national security advantage. One of these tools is investment.”

Over the past three years, Chinese companies have consistently struck out when trying to get US approval for semiconductor deals, not just in the US but across Europe as well. During that period, Cfius has broadened its reach across different geographies and sectors.

The blocking of GSR Ventures’ takeover of the lighting assets of Philips in 2016 was an early sign of that expansion. Since then a number of US and EU deals have been halted over concerns that sensitive technologies with possible military applications could fall into the hands of the Chinese government.

That culminated earlier this month with the blocking of Ant Financial’s attempt to buy US payments company MoneyGram on fears that even the personal financial data of US citizens could be “weaponised”. The paranoia is palpable.

From China’s perspective, approval of the Akrion deal must seem like a huge success, especially given that Naura’s government ownership is no secret.

Cfius’s decision to clear the transaction tells us one of two things: either Akrion’s technology was not considered sensitive, or Washington is loosening up on the types of deals it will allow the Chinese state to buy up.

Xerox: Carl Icahn’s not playing nice

After all the talk by activist investors about taking a more constructive, behind-the-scenes tack in their campaigns, 81-year-old Carl Icahn still isn’t going to play nice.

The billionaire activist fired off a punchy missive to Xerox shareholders on Thursday, slamming chief executive Jeff Jacobson and the “detritus of the Xerox ’old guard’” board members as “incapable” of managing a company or negotiating a merger. Read the full story here.

He says the US printer and photocopier company should revise its joint venture with Fujifilm on terms that are more beneficial to Xerox, or terminate it. He said it was something that “should have been done a long, long time ago”.

“It is self-evident that the current management team is clearly incapable of doing so,” he said. “If the ‘old guard’ directors are similarly incapable, or unwilling to do the work necessary to rectify this dire situation for shareholders, then they must be replaced.”

While Icahn said he would not oppose a possible Xerox-Fuji merger (as reported by the WSJ), he said the current Xerox leadership are “ill-equipped” to negotiate it, and he’d oppose any deal that kept “old guard” directors in place.

“We will not sit idly by and watch Xerox continue to drift towards extinction,” he added.

In other activist news, the problems keep piling up for Bill Ackman.

According to Lex, he is facing a revolt by investors in his publicly traded fund, Pershing Square Holdings, which is listed in London and Amsterdam. A proposal to more than double management’s stake in the $3.4bn vehicle has enraged some shareholders, who claim it puts the interests of Ackman and his fund managers ahead of everyone else. The shareholders are clamouring for buybacks instead.

SoftBank’s unbalanced Uber deal

SoftBank’slong-fought investment in Uber finally closed on Thursday, marking the end of a complex $9.3bn deal that survived many twists and turns over the past seven months.

SoftBank led the deal with $7.7bn of its own money, but one interesting detail that emerged on Thursday is that the other investors who were part of the deal consortium actually got a slightly better deal than SoftBank did.

SoftBank bought $1.1bn worth of new Uber shares at a price of $48.77 a share, and $6.6bn worth of secondary shares from existing shareholders at a price of $32.97 a share. That means that SoftBank’s average price was $34.57 a share and it bought about 223m shares.

However, the consortium that invested alongside SoftBank — a group that included Dragoneer, Tencent, TPG and Sequoia — got a slightly better deal. They bought just $150m worth of expensive primary shares, and spent $1.45bn on the cheaper shares. This means that their average price per share was $34 and they bought about 47m, according to Financial Times calculations.

In other words, SoftBank’s average share price was 17 per cent higher than the consortium’s. Why would SoftBank have agreed to this? We don’t know the answer, but one possibility is that SoftBank needed to bring along other consortium members who would have otherwise balked at the price.

Finally, here’s a scoop from the FT’s Leslie Hook, who spoke to SoftBank’s Rajeev Mishra. He told her that the company should focus on recovering market share in the US and growing in key European markets, a strategy that would end the founders’ original vision of building a transport service “everywhere, for everyone”.

Job Moves

- Blackstone announced that J Tomilson Hill, chief executive of Blackstone Alternative Asset Management, will be moving to a new role as chairman of BAAM. John P McCormick will succeed Hill.

- The UK Takeover Panel has named Justin Dowley as its new deputy chairman starting in May. Dowley is a non-executive director at Melrose Industries and Scottish Mortgage Investment Trust. He spent 30 years as an investment banker at Morgan Grenfell, Merrill Lynch, Gleacher & Co, Tricorn Partners and Nomura.

- Nestlé, the world’s biggest food group, has shaken up its 14-member board by nominating three new independent directors, seven months after activist investor Daniel Loeb criticised the Swiss group as being “stuck in its old ways”. The nominees are Pablo Isla, chief executive of Inditex, Spanish owner of the Zara high street retail chain; Kasper Rorsted, chief executive of Adidas; and Kimberly Ross, a former finance director of Avon, the cosmetics group, and Royal Ahold, the Dutch retailer.

- Anwar Zakkour, global head of TMT at Bank of America, is planning to leave the US bank, CNBC reported. Zakkour has been sole head of the team since March after his colleague Chet Bozdog retired. He joined BofA in 2013 from JPMorgan Chase.

- Allen & Overy has hired Jack Wang as a partner in Shanghai. He will focus on expanding the firm’s corporate M&A practice. Wang joins from Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer and has more than 20 years experience in cross-border M&A.

Greetings from Miami, Gateway to South America. Before going any further, that gives me an excuse to link to a work of comic genius by Peter Sellers:

I have been here at a conference organised by Citi on the near-term future for Latin America. It promises to be an exciting year, as virtually every country in the region will have elections. The bottom line for investors with a taste for risk and an appetite for short-term gains, I would suggest, is that the next 12 months could offer a series of great buying opportunities. I'm not necessarily suggesting that everyone should try doing this at home, but there is a history of foreign investors panicking ahead of Latin American elections.

There are many examples, but by far the greatest was the move in Brazil after Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva (Lula) was first elected in late 2002. That was treated in advance as an Armageddon scenario. When it turned out that Lula was prepared to be pragmatic in power, and that the commodities boom was only just taking hold, shares in Brazil went to the moon. I produced this chart of the MSCI Brazil Index in dollar terms on the Rimes Online website. Note that Brazil's stock market growth under Lula, by far the strongest of any country in the world, was so great that the site defaulted to a log scale:

It is easy enough to spot the point where Lula won the election. There are other examples of this phenomenon at work. Buying Peruvian stocks immediately after the scary populist Ollanta Humala won the election in 2011 would also have been a great deal, for example.

So, what are the opportunities at present? Latin America is not compellingly cheap at present, at least as far as its stock markets are concerned. The region as a whole trades at a trailing price/earnings multiple of 17.7, according to MSCI, which is above the p/e for emerging markets as a whole, of 15.1. Countries south of the Panama Canal are almost all exposed to China — continued growth there will help perceptions of Brazil and the Andean economies, and another slowdown would be harmful. Mexico remains acutely exposed to the US.

Sentiment within the Latin American countries themselves, meanwhile, is rock bottom.

The reason for optimism (at least for those with a tough constitution) is politics. Brazil, Mexico, Colombia, Costa Rica and Paraguay all have elections for head of state this year, as does Venezuela (although there has to be some doubt over whether that one will take place). Cuba will also have a new head of state. This is not going to happen via an election, and will not be market-sensitive, but the island will for the first time in more than half a century be run by a non-Castro and a non-participant in the country’s revolution. It could still turn out to be a big deal.

The two most important elections are impossible to call at this point. Mexico has a single-round election, so presidents can and do win election with less than half of the electorate. The front-runner is Amlo — Andrés Manuel López Obrador, twice narrowly defeated before, a former mayor of Mexico City and the champion of the left. He is charismatic and messianic, and a victory for him would alarm the markets.

The unpopular incumbent PRI party have an experienced technocrat in the race, José Antonio Meade, while in a weird development forced by the electoral system, the traditional parties of right and left have jointly nominated the 38-year-old Ricardo Anaya.

All three candidates are capable of winning a third of the vote, and therefore all three might win. As Mexico is the rare Latin American country that has not given the populist left a turn in the presidency in recent decades, an Amol election would be a vast change.

But I doubt that Amlo should scare people that much. He was my mayor when I lived in Mexico City; he is an oddly ascetic man, who made up for his reluctance to delegate by working very long hours. His daily 6am press conference became something of an institution. But he did show that he could compromise when necessary; his rule was efficient, and less corrupt than most others. I doubt that he is Mexico’s Hugo Chavez, so suspect that a victory for him would create an opportunity to buy, much as Lula's victory did.

I also have a hunch that he may not win. Anaya is a dark horse candidate who has infuriated many in his party by grabbing the nomination. But that sounds like Felipe Calderón 12 years ago. A surprise nominee and total dark horse six months before the election, he managed to make the 2006 campaign a referendum on Amlo and won. It is easy to imagine that happening again.

Meanwhile, Brazil’s politics are in a horrible mess. Trust has broken down in the aftermath of a sweeping corruption scandal, and the field is wide open. The front runners at present are an abrasive law and order conservative, Jair Bolsonaro (whose middle name is actually Messiah), and Lula himself — provided he can get overturned a prison sentence imposed on him for corruption.

This is a nasty mess. Brazil, like Mexico, has an often dysfunctional constitution that can get in the way of necessary decisions being taken. But again, the chances look decent that Brazil will emerge with a viable president, with some kind of a mandate to act (thanks to the two-round system), which has been almost wholly lacking for the last four years of political turmoil.

All that said, a second round that pitted a corrupt former left-wing president against a man widely denounced as a Mei-fascist would not look good to foreign investors. There may yet be a buying opportunity in Brazil before the year is out.

There is one other wild card for Mexico: Nafta. Speaking of which . . .

NAFTA: Ray of light

How great are the risks that the US pulls out of its trade treaty with Mexico and Canada? It is difficult to calculate, as the decision ultimately rests in the mercurial mind of President Donald Trump. However, this piece by ING's James Knightley offers reasons for hope.

Nafta has always faced strong opposition in the US, based partly on very unfair stereotypes of Mexicans. This brilliant parody by Saturday Night Live in 1993 demonstrates how Nafta tended to be presented when it started.

The anti-Mexican populist sentiment into which the Trump campaign tapped was nothing new. Less well understood in the US is that Nafta is just as unpopular in Mexico, as its deeply inefficient agriculture had no chance of competing against US imports. Nafta helped drive waves of Mexican agricultural workers into cities, and also north of the border. In economic terms, these effects were far outweighed by the benefits to Mexican industry and financial services, and all the benefits were swamped once China joined the World Trade Organization. Ultimately, Nafta is a sideshow compared to the rise of China. This is how the US trade deficits with Mexico, Canada and China have evolved over time:

This means a) that the US should not really be bothering with Nafta and b) that if it does leave Nafta or force a major renegotiation, that should be taken as a sign that it is preparing to do something much more drastic in its far more important trade relationship with China. Nafta matters more to Mexico than anyone else, as the following chart shows, and really does not matter all that much to the US. But its significance as a signal to the rest of the world could be immense:

There is always reason for caution in weighing risks that rely on the judgment of Donald Trump. The temptation to do something drastic will be great. But he would face strong opposition from farmers, strong supporters who have benefited greatly from Nafta, and from other interests within the US:

If NAFTA is torn up, businesses in all three economies would experience higher costs and disrupted supply chains while consumers would be faced with higher prices, particularly for cars, clothing food/agriculture and medical devices — areas where tariffs and non-tariff barriers to trade tend to be highest.

Consequently, we are seeing a growing number of politicians within the Republican party warn that ripping up NAFTA would not be in the US’s own interest. 72 members of the House of Representatives wrote a letter in November questioning Drumpf's handling of negotiations while several Senators have expressed concerns. Even the Republican Governor of the key automaker state of Michigan has warned that ripping up NAFTA “would be a negative for all three countries”. Business lobbies have been making similar arguments.

Significantly, the electorate feels similarly. A survey by the PEW research centre conducted at the end of October shows that most Americans (56%) think NAFTA has been good for the US with just 33% saying it has been bad. The response is highly partisan — 72% of Democrat-leaning voters back NAFTA versus 35% for voters leaning Republican, but it hardly suggests that ripping up NAFTA is going to be a major vote winner at the November mid-term elections.

James goes on to make a good argument that the most likely scenario is a continued agreement, with some minor concessions from Canada and Mexico to give the impression that all the hassle was worth it:

Our central case remains that national pride ends up giving way to economic pragmatism, with Canada and Mexico prepared to “give some candy” in the negotiations, as demanded by Trade Representative Lighthizer. Judging by recent official statements, Mexico seems prepared to agree to “strengthen” regional minimum content for the auto sector. Softer language for the sunset clause, to something closer to periodic review rather than automatic termination, also seems plausible, while the parties also appear to be closer on the dispute resolution framework, with Mexico offering the possibility of an “opt-in and opt-out” mechanism for arbitration of trade disputes. But given that Mexico’s counteroffers are likely to meet the US only halfway, it is unclear if they would be sufficient.

An alternative scenario, in which all the parties agree to postpone negotiations, until after July’s Mexican election, would probably be well-received by some investors, seen as evidence that the US is committed to eventually reaching a deal. Others may see a delay in a less favourable light, however, as Mexico’s negotiating stance could change after the elections. The Peña Nieto administration appears better-positioned to negotiate a compromise solution considering the more nationalistic focus of Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador (AMLO), the leading contender in Mexico’s presidential race.

The bottom line should be that there may well be a buying opportunity in Mexico if the current brinkmanship continues, but a deal is ultimately made. The greatest risk to Mexico lies in internal US politics. If the president feels in need of firing up his base later this tear, leaving Nafta would do it. But at present, with economy and markets humming along nicely, that looks unlikely.

Any attempt to end Nafta would reawaken all the fears that prompted investors to be so nervous about a possible Trump presidency before the election. If any one economic decision could turn the current very strong situation on its head, it would be a US exit from Nafta.

Governments around the world will face a fiscal challenge as interest rates begin to rise, bringing an end to the unprecedentedly loose monetary policy of recent years.

Developed economies’ public finances have benefited from the ultra-low rates that suppressed borrowing costs and thus governments’ interest payments — but they have spent all of those savings and presided over rising levels of public debt, according to research by credit rating agency Fitch.

In a world in which rates are beginning to rise, this points to some difficult budget decisions in the coming years.

James McCormack, global head of sovereign and supranational ratings at Fitch, said: “Debt has been increasing but interest payments have fallen — the central banks’ gift. Meanwhile, as debt increased, spending has also increased. So as interest rates rise, there will be some fiscal challenges going forward.”

Fitch estimates that if eurozone interest rates had remained unchanged from 2007 to 2017, collective interest payments by the bloc’s governments would have been nearly €1tn higher.

Lower interest rates have saved eurozone sovereigns an average of 0.8 per cent of GDP per year over the period.

“That is the kind of savings that governments will be looking for in the coming years if interest rates were to reverse,” Mr McCormack said. “It is a big number.” Kate Allen

One area of Wall Street appears on the cusp of receiving a wake-up call in 2018.

The era of ultra low and negative bond yields has propelled plenty of money into dividend-paying stocks. This “bond proxy” trade could well face some big tests in 2018 as central banks retreat at varying paces from their easy monetary policy, while some warn that companies that have muscled up their dividend payouts via cheap debt have reached a limit in raising their payouts.

Less than three weeks into the year, a notable sector divergence underpins the S&P 500, with bond sensitive or defensive areas such as utilities, real estate, telecoms and consumer staples already lagging behind the broad market by a considerable margin.

This rotation has momentum, with global bond managers identifying this strategy as a key feature of their 2018 playbook in the latest Bank of America Merrill Lynch survey.

The dividend trade is also showing signs of lagging behind when we look at the leading 50 blue-chip US companies, dubbed the Dividend Aristocrats as they have increased their annual payout for the each of the past 25 years. While the S&P on a total return basis is already up 3.9 per cent this year, the Dividend Aristocrats index has risen 2.2 per cent, including the reinvestment of dividends.

Much depends on whether bond yields extend their recent rise and as Deutsche Bank notes, “dampen the bond proxy trade”.

Another issue for the market is whether companies can keep increasing dividends particularly as higher oil prices and rising wages are set to squeeze corporate margins.

Deutsche highlights that before the financial crisis, the average S&P company paid out one-third of its earnings as a dividend, whereas it has now reached one-half. The bank thinks “investors have begun to realise [companies] have reached capacity in the amount of debt they can take on to finance both outsized dividends and share buybacks — as net debt has more than tripled as a proportion of earnings — in the past decade.

“This increase in leverage to fund capital returns can only happen once investors valued these stocks on the basis it could persist.’’

That leads the bank to conclude: “While equity investors remain fixated on the market’s valuation relative to earnings, it is the dividend bubble quietly inflating in the background that should be of far greater concern.” Michael Mackenzie

Higher inflation and a tapering of central bank bond-buying programmes are not the only threats to the holders of US government bonds. One worry, a wave of supply, is being flagged by economists and strategists.

Economists with Deutsche Bank expect the extra debt the Treasury must issue to fund President Donald Trump’s tax package and the amount of debt the Federal Reserve plans to redeem at maturity this year will bloat issuance to about $1tn in 2018. That’s up more than 50 per cent from a year earlier and, when coupled with a 30 per cent rise in the amount of corporate debt that’s due to mature, leaves questions of who the eventual buyer will be.

“If demand for US fixed income doesn’t double over the coming years then US long rates will move higher, credit spreads will widen, the dollar will fall, and stocks will probably go down as foreigners move out of depreciating US assets,” Torsten Sløk, an economist with the bank, said.

That extra supply should arrive as central banks withdraw crisis-era stimulus. Robert Michele, JPMorgan Asset Management’s global head of fixed income, expects that support to “fade away”. “You’ll have to find someone else who wants to step up at these levels.”