The Financial Times is committed to a more comprehensive and in depth coverage of the Oil and Gas Industry.

Chevron, the US oil and gas group, has good opportunities for growth and will not be focused solely on cost cutting under its new chief executive, the company’s outgoing leader has said.

The group announced on Thursday morning that, as expected, John Watson, who has led Chevron since the start of 2010, would be stepping down. He will be replaced by Michael Wirth, who has been running its midstream and development operations.

The board’s decision to appoint Mr Wirth, who has spent his career mainly in the cost-conscious “downstream” refining, chemicals, and trading businesses, has prompted suggestions that under his leadership Chevron would concentrate on reducing spending.

However, Mr Watson said that while being able to manage costs was important, “the heavy sledding on capital and cost reduction is behind us”.

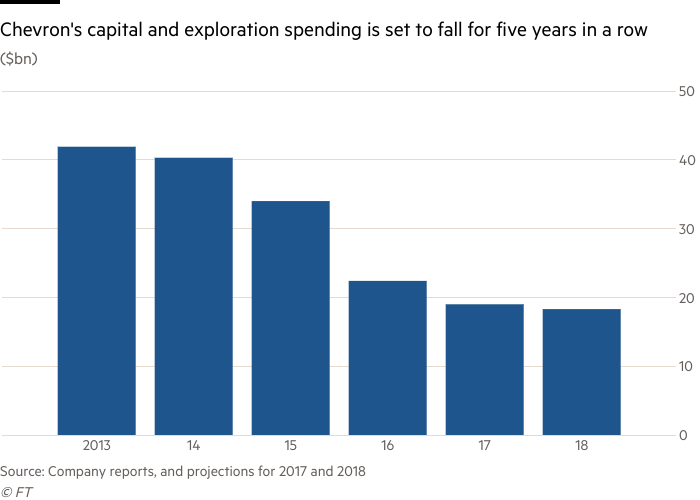

Chevron’s capital and exploration budget of $19.8bn for this year is about half what it was at its peak in 2013-14, and operating expenses are back down to where they were eight years ago, Mr Watson said.

Chevron’s operations in shale oil and gas in the Permian Basin of Texas and New Mexico, the Duvernay formation of western Canada and the Vaca Muerta of Argentina, as well as the $37bn Tengiz expansion project in Kazakhstan, were important prospects for future growth, he added.

Another priority will be improving the performance of Gorgon and Wheatstone, two huge liquefied natural gas projects in Australia. The projects were delayed and their combined cost overshot their original budgets by $22bn — half of which was borne by Chevron, half by its partners — but both have now been completed and are ramping up production.

“We’re at an inflection point where spending is coming down and production is coming up,” Mr Watson said. “And if you get any help from the commodity markets, that’s a pretty nice formula.”

Mr Wirth, who will take over on February 1 next year, joined Chevron as a design engineer in 1982 and has spent his career working in engineering, construction and operational roles, including a nearly 10-year stint as executive vice-president for the downstream and chemicals businesses.

Mr Watson said he had told the board last December that he was planning to step down, and Mr Wirth was appointed the group’s vice-chairman in February, in a sign that he was the intended successor.

The cost overruns at Gorgon and Wheatstone had contributed to the board’s view that it was time for Mr Watson to go, according to a person familiar with directors’ thinking.

Asked about regrets from his time as chief executive, Mr Watson raised the problems of those megaprojects.

“The flurry of activity in the middle part of the decade, and the attendant impact on costs . . . we’re trying to learn from,” he said.

“The projects themselves will be good over the course of time, but there are certainly some things that we are doing differently, to try to minimise cost and schedule overruns on projects.”

Chevron’s performance in terms of shareholder returns during his tenure has been better than for any of his peers among the large international oil companies.

Mr Watson said avoiding over-priced acquisitions had been one factor contributing to that success.

“That [M&A] hasn’t been something that’s been a requirement for us to be successful,” he said. “And we’ve outperformed by a wide margin with this philosophy.”

Another feature of his record that he took pride in, Mr Watson said, was the improvement in Chevron’s safety performance.

The BP Deepwater Horizon disaster in April 2010, soon after Mr Watson took over at Chevron, prompted a company-wide effort to improve safety, and measures such as the number of spills have improved sharply during his tenure.

“We’ve done an enormous amount of work on well control, and in our refineries on process safety,” he said.

“We’ve really, really improved, and in most areas are leading the industry. The absence of incidents, nobody thinks about. But we’ve really made a lot of progress in that area and are very proud of that.”

ExxonMobil and Chevron, the two largest US oil and gas groups, are continuing to lose money on oil and gas production in their home country, in spite of the rise in commodity prices since last year.

The losses raise a question over the companies’ forecasts of strong growth in US production, particularly in the Permian basin of Texas and New Mexico.

Reporting earnings for the third quarter, Exxon said it lost $238m on oil and gas production in the US, while Chevron lost $26m. The losses were reduced from the equivalent period of 2016, but came as both companies made healthy profits on their international operations.

In presentations for analysts on Friday, both companies set out projections showing strong growth in production from US shale resources. Exxon forecast average annual growth of 20 per cent in its shale oil and gas production, with 45 per cent growth in the Permian region.

It has been building up its position in the region in recent years, and in September did another deal to acquire more drilling rights, increasing its 6bn barrels of oil equivalent resource base by a further 400m boe.

Chevron similarly projected strong growth in production in the Permian Basin, where it has retained a large legacy position built up over decades.

John Watson, Chevron’s chief executive who is stepping down at the end of January, said the company was “exceeding expectations” in the Permian. However, unlike “conventional” oil developments, where an initial capital cost to drill wells and install facilities is followed by a long period of production that declines only slowly, shale resources require continual drilling to maintain output.

Raising profitability while increasing production in shale will require Exxon and Chevron to cut costs by drilling those multiple wells more efficiently and maximising their productivity, analysts say.

On a call with analysts, Exxon said it was aiming to have “industry leading development costs”, helped by drilling longer horizontal wells than have been standard in shale. It plans soon to start drilling its first three-mile horizontal well in the Permian basin.

The two companies discussed their similar plans for the US as they reported differing sets of earnings. Exxon beat analysts’ expectations with earnings per share up 48 per cent at 93 cents for the quarter.

The results would have been even better but for the disruption to Exxon’s refineries and other operations caused by hurricane Harvey, which cut an estimated 4 cents from earnings per share.

Darren Woods, the new chief executive who took over from Rex Tillerson at the start of the year, described the earnings as a “solid performance” and “a step forward in our plan to grow profitability”.

Strong results from oil and gas production elsewhere in the world offset the losses in the US, and overall upstream earnings more than doubled to $1.57bn from $620m in the third quarter of last year.

Chevron, meanwhile reported a 51 per cent rise in earnings per share to $1.03 for the third quarter, helped by the strength of its downstream refining and marketing operations and a one-off gain of $675m. Excluding that gain and other one-off items, earnings per share were 85 cents below analysts’ average forecast of 99 cents.

They were the first set of results to be published since Chevron confirmed last month that Michael Wirth, executive vice-president for midstream and development at the group, would be taking over from Mr Watson as chief executive.

In a statement, Mr Watson said the company’s cash flow was “at a positive inflection point, with oil and gas production increasing and capital spending falling”.

He said projects such as the huge Australian liquefied natural gas plants Gorgon and Wheatstone had been completing construction, coming on line and starting to ramp up production, boosting cash flows.

Production volumes show the benefits of Chevron’s heavy capital investment in recent years starting to kick in, with output up 8 per cent compared to the equivalent period of 2016 at 2.72m barrels of oil equivalent per day, but that is not showing up very strongly in profits yet.

In spite of the rise in oil and gas prices over the past year, Chevron’s production operations reported earnings up just 8 per cent at $489m.

Downstream earnings from refining, marketing and chemicals were up 70 per cent at $1.81bn.

Chevron is stepping up investment in US shale production, even as the second-largest US oil and gas group prepares to cut its total capital spending for a fifth year in succession.

The company on Wednesday afternoon announced a budget for capital and exploration spending for 2018 of $18.3bn, about 4 per cent lower than the expected out-turn for 2017.

Within that, however, there will be a sharp acceleration in its planned investment in shale. The company intends to invest $2.5bn in shale this year, most of it in the Permian Basin of Texas and New Mexico. For next year, it plans to increase that by about 70 per cent to $4.3bn, with $3.3bn going to the Permian alone.

Other large US oil producers, including ExxonMobil and ConocoPhillips, have also been stepping up investments in shale to drive production growth.

John Watson, Chevron’s chief executive who is leaving the company on February 1, said in a statement that the company was spending about three-quarters of its capital and exploration budget on projects that would start returning cash within two years, a category that includes most shale developments.

He added that driven by strong growth in output in the Permian, the 2018 plan should “deliver both strong production growth and solid free cash flow, at prices comparable to what we’ve seen this year”.

The overall reduction in planned capital and exploration spending reflected improved efficiency and moves to focus on only the investments with the highest returns, as well as the completion of its liquefied natural gas megaprojects in Australia, Mr Watson said.

Chevron has already cut its annual spending from a peak of $41.9bn in 2013 to about $19bn this year, as it has completed the LNG projects, Gorgon and Wheatstone. Gorgon, which started production last year, and Wheatstone, which started in October, had a combined cost of about $88bn, of which Chevron’s share was about $47bn.

The company has made clear that any expansion of those projects, which was still being worked on last year, is now not on its agenda, as it focuses on investments with a quicker payback. The one large development Chevron is still committed to, with a planned $3.7bn investment next year, is the Future Growth Project in Kazakhstan, an expansion of its highly lucrative Tengiz oilfield. In a sign of the field’s importance to Chevron, planned spending on it accounts for two-thirds of the company’s total budget for big capital projects for next year.

Chevron’s plans to cut total capital and exploration spending contrast with the budgets set out by ExxonMobil, which is the largest US oil and gas group, and ConocoPhillips, which is the largest exploration and production company.

Exxon raised its capital budget by 16 per cent for this year compared with last year’s spending, and has said it plans a further 14 per cent increase next year. Conoco cut spending this year, but last month set out plans to step it up again for the next three years. Both Exxon and Conoco, like Chevron, are aiming for rapid growth in the Permian Basin.

Seen from the executive floors of the oil majors, the legal action launched against five of the world‘s largest oil companies at the beginning of January by New York City is a pinprick. The case is obviously political — there must be an election coming. Taking on Big Oil signals a candidate’s stance and helps to raise money. Such grandstanding is nothing new. The lawyers will deal with it, while real business goes on elsewhere.

But what if this view is wrong?

The legal action against BP, Chevron, ConocoPhillips, ExxonMobil and Royal Dutch Shell triggered by superstorm Sandy’s devastation in 2012, is claiming compensation for the costs of improvements in infrastructure resilience necessitated by the risks of climate change and extreme weather. It is just the latest in a series of cases in the last two years.

In California, two cases brought respectively by the cities of San Francisco and Oakland and by San Mateo and Marin county are claiming compensation from a long list of companies for damage knowingly caused by production of oil, gas and coal.

This year, 21 teenagers will get a hearing in the California appeals court for their claim in Juliana v US that the government failed to protect their rights to life, liberty and property by promoting the use of fossil fuels.

Meanwhile in Germany a Peruvian mountain guide, Saul Luciano Lliuya, is suing RWE for what he claims is its contribution to the melting of a glacier in the Andes that threatens to flood his home town of Huaraz. In his view, the utility has contributed 0.5 per cent of all emissions produced since the industrial revolution.

So far, the oil and gas companies' defence has been that the casual links are unproven and there are too many triggers of climate change for any court to attribute responsibility to them.

I am not qualified to judge the points of law in these cases. But what matters for the claimants is not really the legal judgments or the money sought. It is the publicity for what appears to be a co-ordinated and well-funded campaign, with the goal of casting a shadow over the companies’ future profitability and therefore their market value. A secondary goal is reputational damage.

There will no doubt be more cases in more countries and it would not be surprising if a judge found in favour of the claimants, forcing the companies to escalate the matter up through the judicial system. It will be a great time for lawyers.

The question is whether the cumulative impact of the legal approach will have a greater effect than campaigners’ stunts at art galleries and museums. A combination of circumstances suggest that it might.

Although it is not always obvious, the industry is undergoing serious introspection about its strategic future. This is driven by three factors: the adoption around the world of public policies against climate change; the difficulty of accessing new, low-cost reserves of oil (gas is too plentiful to guarantee decent margins); and, perhaps most important, the continuing fall in the costs of renewables led by wind and solar. The big energy companies — which are anything but stupid — see change coming.

Public policy may be incoherent in the absence of a carbon price but the direction of regulation, subsidies and other government interventions in the market has shifted not just in the developed world but also in China and India.

For most of the companies (with one or two notable exceptions over the past year) replacement levels for the volumes of oil being produced have fallen to very low levels because too many areas remain closed and many of those that are open are not commercially viable.

And in the North Sea and China, and soon across the world, renewables are approaching grid parity, with costs likely to fall still further as the sector is restructured and economies of scale kick in. Grid parity means that wind and solar — in the right places — will shortly need no subsidy at all.

So, while oil demand continues to grow, the majors' market share will decline, particularly in the growth markets of Asia. These groups think long term, and need to find a new business model. The small steps taken so far suggest that they see themselves becoming energy companies with a span of activities including electricity supply and renewables.

Legal campaigns will not stop climate change. That is down to the scientists and engineers who must find low-cost, low-carbon sources of supply to meet the needs of 8bn and then 9bn people globally. In public, the oil majors dismiss what they see as political theatre, but there is growing concern that scientific work linking hydrocarbons to climate change and climate change to extreme weather could produce judgments against the industry as a whole and perhaps individual groups.

The companies do not believe that point has yet been reached. For now, the legal actions add a further dimension to the pressure for change in an industry that has begun to accept the need to reinvent itself.

Chevron, the second-largest US oil and gas group, has reported a 51 per cent rise in earnings per share to $1.03 for the third quarter, helped by the strength of its downstream refining and marketing operations.

Earnings per share were above analysts’ average forecast of 99 cents, but were helped by an asset sale gain of $675m.

Adjusting for that and other one-off items, earnings per share were below analysts’ expectations at 85 cents.

These are the first set of results to be published since Chevron confirmed last month that Michael Wirth, executive vice-president for midstream and development at the group, would be taking over from John Watson as chief executive. Mr Watson, who has led Chevron since 2010, is scheduled to step down at the end of January.

In a statement, Mr Watson said the company’s cash flow was “at a positive inflection point, with oil and gas production increasing and capital spending falling.”

He said projects such as the huge Australian liquefied natural gas plants Gorgon and Wheatstone had been completing construction, coming on line and starting to ramp up production, boosting cash flows.

He said Chevron’s shale drilling activity in the Permian Basin of Texas and New Mexico was “exceeding expectations,” and added: “We expect this pattern to continue.”

Production volumes show the benefits of Chevron’s heavy capital investment in recent years starting to kick in, with output up 8 per cent compared to the equivalent period of 2016 at 2.72m barrels of oil equivalent per day, but that is not showing up very strongly in profits yet.

In spite of the rise in oil and gas prices over the past year, Chevron’s production operations reported earnings up just 8 per cent at $489m.

Downstream earnings from refining, marketing and chemicals were up 70 per cent at $1.81bn.

Over the past decade, Chevron’s shares have greatly outperformed those of its rival ExxonMobil, rising by 33 per cent while Exxon’s fell 9 per cent. However both companies have lagged behind the S&P 500 index, which rose 71 per cent over that period.

ExxonMobil, the world’s largest listed oil and gas group, will start publishing reports on the possible impact of climate policies on its business, bowing to investor demands for improved disclosure of the risks it faces.

The decision is the biggest success so far for investors who have been pushing companies to do more to acknowledge the threat they face from climate change and from policies that curb greenhouse gas emissions.

In a regulatory filing on Monday evening, Exxon said it would introduce “enhancements” to its reporting, including analysis of the impact of policies designed to limit the increase in global temperatures to 2C, an internationally agreed objective.

At Exxon’s annual meeting in May, investors controlling about 62 per cent of the shares backed a proposal filed by a group of shareholders led by the New York state employees’ retirement fund calling for an annual assessment of the impact of technological change and climate policy on the company’s operations.

Supporters of the proposal argued that the disclosures would help shareholders assess the long-term resilience of Exxon’s operations in a world where governments delivered on their pledges to tackle global warming.

The company’s board had opposed the proposal, arguing that, while directors agreed with the need for scenario planning and risk analysis, they were already “confident that the company’s robust planning and investment processes adequately contemplate and address climate-related risks and are sufficient to ensure delivery of long-term shareholder value”.

In Monday’s filing, the company said the board had “reconsidered the proposal . . . [and] sought input from a number of parties, such as the proponents and major shareholders” before deciding to accede to improved reporting on climate policy risk.

Under Lee Raymond, who led Exxon during 1993-2005, the company stressed the “gaps” in climate science, and was vehemently opposed to international attempts to address the threat under the 1997 Kyoto protocol.

However, under previous chief executive Rex Tillerson, who led the company during 2006-16 and is now US secretary of state, Exxon acknowledged the need to address the threat of climate change, and supported the Paris agreement, which set a goal of limiting the rise in global temperatures since pre-industrial times to “well below” 2C.

Darren Woods, who took over as chief executive at the start of the year, has gone further, launching a programme to cut leaks of methane, a potent greenhouse gas, from the company’s operations, and signing up to initiatives to reduce emissions launched by international oil groups and by the American Petroleum Institute, the industry group.

Its new disclosure policies could mean Exxon will have to discuss more radical changes. Among the issues that the company has said it will assess in its new disclosures are the sensitivity of energy demand to policy changes, and “positioning for a low-carbon future”.

Several oil companies, particularly in Europe, have seen an opportunity in climate policy, arguing that more should be done to shift power generation away from coal and towards natural gas, which emits less carbon dioxide for an equivalent amount of electricity.

Norway’s trillion-dollar sovereign wealth fund has proposed dropping its investments in oil and gas stocks, warning that the country — western Europe’s biggest energy producer — already has enough exposure to petroleum.

The Norwegian central bank, which runs the Oslo-based fund, believed dumping its oil and gas holdings, which include stakes in companies such as BP, Royal Dutch Shell, Total, Chevron and ExxonMobil — would make the country’s wealth “less vulnerable to a permanent drop in oil and gas prices”.

The central bank said Norway’s own energy sector and the government’s controlling stake in Statoil, the national oil company, was the driver for its proposal, which will be closely watched given the fund’s clout in global equity markets.

The bank said in a letter to the finance ministry that it took no view on the future path of oil and gas prices or the “sustainability” of the sector, but the proposal follows a three-year downturn in energy prices that has hurt the country’s growth and government revenues.

It said about 6 per cent of its fund, which crossed the $1tn level for the first time earlier this year, is invested in the oil and gas sector.

Oil and gas companies have long-feared divestment by funds on ecological grounds as well as those who have warned about oil demand peaking in the coming decades.

“This is a victory for common sense,” said Truls Gulowsen, head of Greenpeace Norway, who said this would help lower the country’s “financial carbon risk”.

While the Norwegian central bank said the proposal is about diversifying the source of the country’s wealth as it has grown, it nevertheless will be closely watched by other fund managers.

The central bank said its analysis suggested that during times of stable oil prices, energy stocks were closely correlated with the broader market, but tended to fall much harder when oil and gas prices dropped.

The fund, known officially as the Government Pension Fund Global, is not expected to sell immediately because the proposal needs to be approved by the government and parliament.

However, shares in some of the companies most affected fell, with Shell — the biggest oil and gas holding with a $5.3bn stake — down 2.5 per cent in London. ExxonMobil, the second-largest oil and gas holding of about $3bn, was down 1.3 per cent.

The oil fund also holds more than $6bn split almost equally between BP, Chevron and Total.

Norway produces more than 3.7m barrels of oil equivalent a day of liquids and gas output, making it western Europe’s biggest energy producer, despite a population of just 5.2m people.

It was widely seen as having avoided the worst excesses of the so-called “oil curse”, partly by funnelling much of the revenue into funds to help save for the future and insulate the wider economy.

The so-called oil fund was launched in 1990 to make global investments and has expanded to hold almost $200,000 per head of population.

“The fund has grown rapidly and is an increasingly large part of the country’s GDP and government spending, so there is more attention on how it is being managed”, said Hilde Bjornland, an economics professor at the BI Norwegian Business School.

“If there was a large decline in the fund now there would be a much bigger impact on the public finances.”

Norway’s finance ministry said it would study the proposal, with the government expected to make a decision in autumn 2018.

Royal Dutch Shell’s decision to sell electricity direct to industrial customers is an intelligent and creative one. The shift is strategic and demonstrates that oil and gas majors are capable of adapting to a new world as the transition to a lower carbon economy develops. For those already in the business of providing electricity it represents a dangerous competitive threat. For the other oil majors it poses a direct challenge on whether they are really thinking about the future sufficiently strategically.

The move starts small with a business in the UK that will start trading early next year. Shell will supply the business operations as a first step and it will then expand. But Britain is not the limit — Shell recently announced its intention of making similar sales in the US.

Historically, oil and gas companies have considered a move into electricity as a step too far, with the sector seen as oversupplied and highly politicised because of sensitivity to consumer price rises. I went through three reviews during my time in the industry, each of which concluded that the electricity business was best left to someone else.

What has changed? I think there are three strands of logic behind the strategy.

First, the state of the energy market. The price of gas in particular has fallen across the world over the last three years to the point where the International Energy Agency describes the current situation as a “glut”. Meanwhile, Shell has been developing an extensive range of gas assets, with more to come. In what has become a buyer’s market it is logical to get closer to the customer — establishing long-term deals that can soak up the supply.

Given its reach, Shell could sign contracts to supply all the power needed by the UK’s National Health Service or with the public sector as a whole as well as big industrial users. It could agree long-term contracts with big businesses across the US. To the buyers, Shell offers a high level of security from multiple sources with prices presumably set at a discount to the market. The mutual advantage is strong.

Second, there is the transition to a lower carbon world. No one knows how fast this will move, but one thing is certain: electricity will be at the heart of the shift with power demand increasing in transportation, industry and the services sector as oil and coal are displaced.

Shell, with its wide portfolio, can match inputs to the circumstances and policies of each location. It can match its global supplies of gas to growing Asian markets while developing a renewables-based electricity supply chain in Europe. The new company can buy supplies from other parts of the group or from outside. It has already agreed to buy all the power produced from the first Dutch offshore wind farm at Egmond aan Zee. The move gives Shell the opportunity to enter the supply chain at any point — it does not have to own power stations any more than it now owns drilling rigs or helicopters.

The third key factor is that the electricity market is not homogenous. The business of supplying power can be segmented. The retail market — supplying millions of households — may be under constant scrutiny with suppliers vilified by the press and governments forced to threaten price caps but supplying power to industrial users is more stable and predictable, and done largely out of the public eye. The main industrial and commercial users are major companies well able to negotiate long-term deals.

Given its scale and reputation, Shell is likely to be a supplier of choice for industrial and commercial consumers and potentially capable of shaping prices. This is where the prospect of a powerful new competitor becomes another threat to utilities and retailers whose business models are already under pressure.

In the European market in particular, public policies that give preference to renewables have undermined other sources of supply — especially those produced from gas. Once-powerful companies such as RWE and EON have lost much of their value as a result. In the UK, France and elsewhere, public and political hostility to price increases have made retail supply a risky and low-margin business at best. If the industrial market for electricity is now eaten away, the future for the existing utilities is desperate.

Shell’s move should raise a flag of concern for investors in the other oil and gas majors. The company is positioning itself for change. It is sending signals that it is now viable even if oil and gas prices do not increase and that it is not resisting the energy transition. Chief executive Ben van Beurden said last week that he was looking forward to his next car being electric. This ease with the future is rather rare. Shareholders should be asking the other players in the old oil and gas sector to spell out their strategies for the transition.

The growth of Royal Dutch Shell’s oil and gas operations in the next decade will depend on shale production, its chief executive has said, in the latest sign of western energy groups pinning their hopes for expansion on those “unconventional” resources.

Ben van Beurden told the Financial Times that he saw chemicals, electricity and biofuels as key sectors for Shell’s long-term future, as he positioned the company to face tightening constraints on burning fossil fuels. But he was also planning for growth in Shell’s traditional core oil and gas production business, focused on shale reserves in the US, Canada and Argentina.

Depending on how oil prices looked in the 2020s, he said, the company would probably want to keep investing in shale “because we will really want to grow this business quite quickly”.

Shell has suffered prolonged difficulties in shale in the past, and in 2013 had to take a $2.1bn writedown on the value of unconventional oilfields in the US and Canada. But Mr van Beurden believes it has now improved the performance of the business enough to allow it to expand while making a profit.

The strategy aligns Shell with peers ExxonMobil and Chevron, the two largest US oil groups, which are looking to US shale reserves as a principal source of new production over the next few years.

Shell is stepping up investment in the Permian Basin of Texas and New Mexico and the Duvernay shale in Alberta, and expects to double total production of unconventional oil and gas from about 250,000 barrels of oil equivalent a day last year to about 500,000 boe/d by the end of the decade.

Mr van Beurden said Shell had been working hard in the past few years to cut production costs in shale, and with “a little bit of help from the oil price going up, we now see that we can significantly accelerate investment into this opportunity”.

The endemic problem of US shale development for all producers is that it has been hard to generate positive cash flow. Because production from each well declines very quickly in its first few years, companies need to keep drilling more to maintain output. But Shell says it has cut the cost to drill and complete each well in the Permian by 35 per cent over the past two years, and it expects to be generating free cash flow from its shale operations by 2019.

Lower costs and the recovery in oil prices meant “you will see a tremendous amount of growth” in cash generation from shale, Mr van Beurden said.

Over the next few years, Shell is expecting a boost to oil production from its deep water offshore assets in Brazil and the US Gulf of Mexico, and could invest in new liquefied natural gas production plants in the US and Canada.

Into the 2020s, however, it plans a greater focus on revenue streams that will be less constrained by policies to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, including petrochemicals and electricity. Shell has made a series of moves in recent months to strengthen its position in the power industry, with deals to buy Texas electricity group MP2, electric vehicle charging company NewMotion, and UK energy retailer First Utility.

“If you fast forward with another twenty, thirty, forty, fifty years, the power segment is going to be a very dominant part of the total energy system,” Mr van Beurden said. “At the moment it’s only 18 per cent but it will be more than 50 by the time this century is over. So we cannot pass up on that opportunity.”

There is a limit to how big a role US shale can play in the global oil market, according to the chief executive of BP, who said traditional producers such as Saudi Arabia would continue to exert more influence over crude prices.

Bob Dudley said he had become less worried about the extent to which US shale resources could hold down prices as more was learned about their geology.

“There are cracks appearing in the model of the Permian being one single, perfect oilfield,” he told the Financial Times, referring to the region of Texas and New Mexico at the centre of the shale revolution.

Surging production of US shale oil and gas, made possible by advances in drilling technology which has given access to hydrocarbons trapped in “tight” rock formations, has weakened the stranglehold of Opec producer nations over the crude market.

But Mr Dudley said that emerging technical challenges called into question the ability of shale companies to rival conventional producers over the long term.

“I don’t think [US shale] will be the perfect swing producer now,” he said. “For a while, I was worried. But I think it is going to be less solid.”

The Opec cartel, acting with Russia, has reasserted its influence over the market in the past year by agreeing production cuts that have pushed crude prices back above $60 a barrel after a deep three-year downturn caused by the shale boom.

The recovery in prices has spurred growth in US tight oil output, which the International Energy Agency said this month would cause global supplies to exceed demand in the first half of next year.

However, analysts at Wood Mackenzie, the energy consultancy, have warned that expansion of US shale production will become harder in the 2020s as the “easiest” resources are drained.

US “supermajors” ExxonMobil and Chevron are among those investing heavily in US shale, even as independent producers such as Marathon Oil and Continental Resources face investor scrutiny over poor returns on capital.

BP has significant onshore US gas resources from Wyoming to Texas and it is also investing in Argentine shale. But most of its capital remains committed to large conventional oil and gas projects.

Competition from shale has deterred investment in conventional resources in recent years, leading some in the industry to predict an oil supply crunch.

“I’m not yet in the camp that we’re going to end up with a big price spike because of low investment,” said Mr Dudley. “There’s a lot of investment that’s been deferred, that’s for sure. But there are other swing producers like Saudi Arabia who can pull it back.”

Mr Dudley acknowledged that oil faced long-term competition from electric vehicles but said the technology had been “hyped” and that environmental problems surrounding the mining and disposal of materials used in lithium-ion batteries that power electric vehicles had been under-estimated.

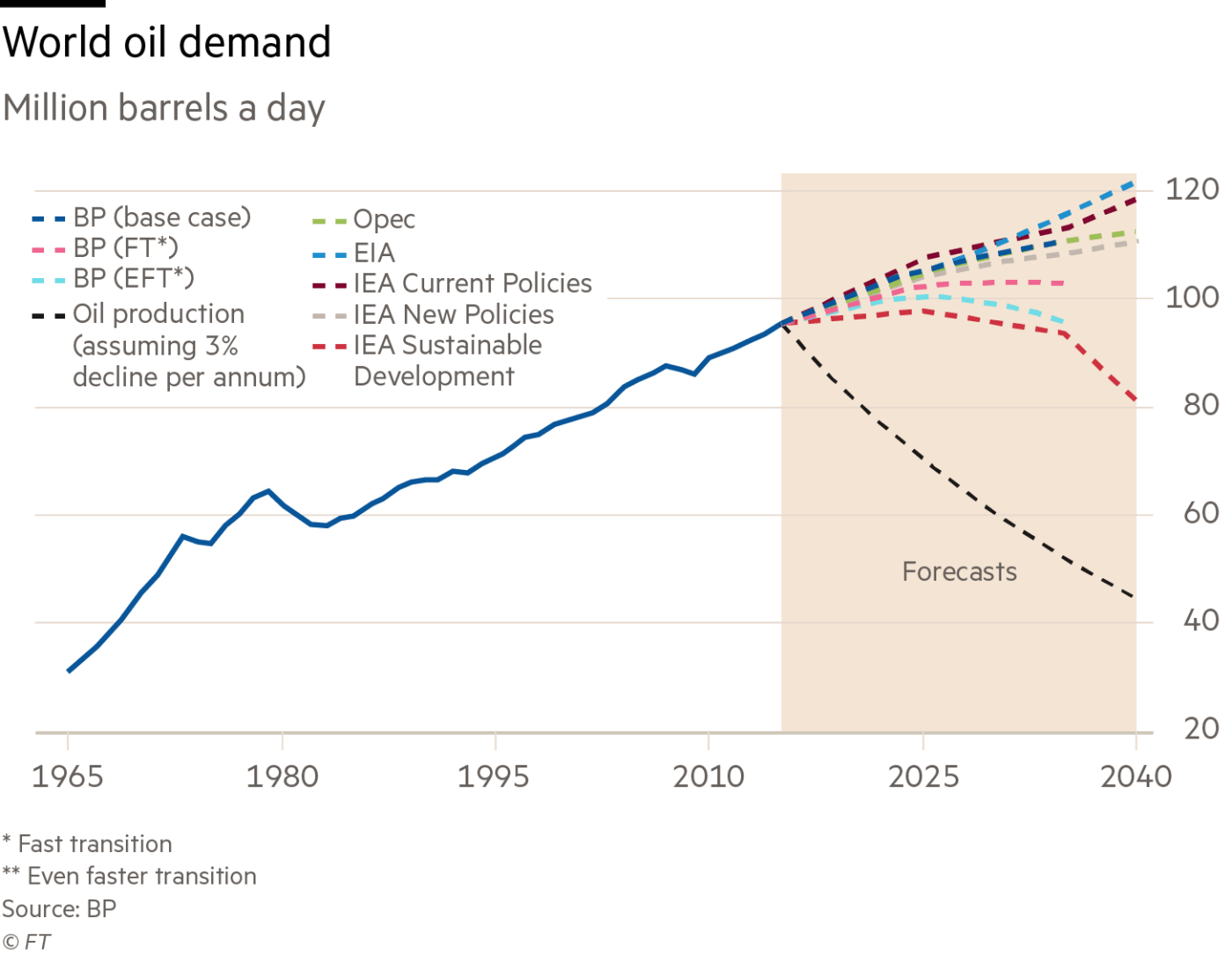

He added: “For at least 10 years, and probably longer, oil demand will go up because of prosperity and population growth. And then, when it starts to go down, it’s going to be a gradual decline. So there will be, until well into the second half of the century, a need for oil.”

Royal Dutch Shell has approved its first significant development in the North Sea in more than six years, in a sign that big energy companies are still on the hunt for opportunities in one of the world’s most mature oil and gas basins.

Shell said it would redevelop the Penguins field north-east of the Shetland Islands, together with its partner ExxonMobil, in a project expected to cost more than $1bn.

The decision marks one of the biggest investments in the North Sea since oil prices crashed in 2014 and will increase confidence that the UK oil and gas industry is gradually recovering after a brutal downturn.

Last year, Shell sold more than half its UK production base to Chrysaor, a private equity-backed company, in a deal that reinforced perceptions that the biggest oil and gas producers were retreating from the North Sea.

However, the group has stressed commitment to its remaining UK portfolio and said on Monday that it was aiming to increase its North Sea production in coming years.

“Penguins demonstrates the importance of Shell’s North Sea assets to the company’s upstream portfolio,” said Andy Brown, head of exploration and production for Shell.

Redevelopment of Penguins will involve construction of a floating production, storage and offloading vessel (FPSO) with capacity for peak output of about 45,000 barrels of oil and oil equivalent per day.

Shell, which operates Penguins in a 50-50 partnership with Exxon, said it would be the first new manned installation in the northern North Sea for almost 30 years.

Production from Penguins is routed via Shell’s nearby Brent Charlie platform but the field needs its own new infrastructure to keep oil flowing into the 2020s because the 40-year-old Brent field is in the process of being decommissioned.

There had been fears after the 2014 oil price crash that younger North Sea fields such as Penguins, first developed in 2002, and remaining untapped resources would be left stranded as oil companies decommissioned old platforms and pipelines.

But sharp cost cuts of up to 40 per cent over the past three years have improved the region’s competitiveness and eased concern about the risk of precipitous decline.

Shell said oil from the redeveloped Penguins field would have a break-even point below $40 a barrel. Brent crude, the international benchmark, is currently trading around three-year highs close to $70 a barrel.

Recovery in oil prices is increasing cash flows for Shell and its peers after a long period of financial pain. This is spurring gradual recovery in investment in exploration and production, although the mood in the industry remains cautious.

Andy Samuel, chief executive of the Oil and Gas Authority, which regulates the UK industry, said he expected “further high value projects to move forward...this year, which will help prolong UK production for many years”.

Saudi Arabia’s energy minister took a rare sideways swipe at the International Energy Agency on Wednesday, accusing the body of overhyping the impact of US shale growth on the oil market.

In a retort to remarks by IEA head Fatih Birol, Khalid Al Falih said at an energy panel in Davos that the agency was failing to put the scale of US production increases into context.

“I was not disputing the amazing revolution of shale...[but] in the overall global supply demand picture it’s not going to wreck the train,” said Mr Falih.

“We should not be scared,” he added, at the World Economic Forum’s annual conference on Wednesday. “That’s the core job of the IEA, not to take it out of context.”

Mr Falih appeared alongside his Russian counterpart Alexander Novak and US energy secretary Rick Perry, who together now represent countries pumping more than a third of the world’s crude.

The appearance of a US representative on a panel of traditional producer nations illustrates the transformative effect the shale boom has had on global energy markets.

The IEA said last week US crude production was on course to overtake Saudi Arabia and rival Russia, with the body revising 2018 growth forecasts for the US higher to output of more than 10m b/d.

The Paris-based body stressed that “explosive” expansion in shale was offsetting Opec-led supply cuts, a fear held among many countries participating in a deal to curb production that stared in 2017.

Mr Falih argued that rapid global oil demand growth and natural decline rates at existing fields meant greater supplies would be needed, adding there was an “oversized focus” on US shale growth.

The Saudi minister said US output would be “absorbed” just as rising supplies in the 1980s were eventually needed by the market. His comments may raise eyebrows because the boom in North Sea and Alaskan output at that time led to two decades of relatively low prices and is seen as a major factor behind the eventual collapse of the Soviet Union.

His comments come as Saudi Arabia attempts to transform its economy as part of an overhaul of the state, driven by the kingdom’s crown prince Mohammed bin Salman. Riyadh, however, needs higher oil prices to finance widescale economic and social reforms, including the planned share sale of state oil company Saudi Aramco.

Mr Birol was not on the panel, but made a statement as a member of the audience. “I believe the shale revolution is coming very strongly and we will see more and more impacts of that in years and years to come,” he said.

Despite Mr Birol’s bullish outlook on US shale the IEA has long argued the world needs greater investment in future production to meet growing energy demand.

But the agency has faced criticism for its monthly oil market forecasts, which some in the industry have said tend to focus too heavily on short term supply growth, creating unnecessary uncertainty for investors.

On the supply cut deal, Mr Falih said it is “very unlikely” global producers, including Russia, would unwind their production curbs at the ministers’ next formal meeting in June. He said eventually there would be a “gradual, smooth exit” so as not to “shock” the market in 2019.

Mr Perry, the US energy secretary, said that the emergence of the US as a major oil producer to rival Saudi Arabia and Russia meant that there may be areas in which the three countries could work together.

He said they were “blessed” to be able to supply the world with fossil fuels. But he made clear President Donald Trump’s administration was not seeking too close an alliance with the US’s rivals.

“America First means one thing: competition”.

The electric car revolution and stricter global rules on emissions have focused debate in the energy sector on when decades of growth in oil demand will eventually peak. But Spencer Dale, chief economist at energy major BP and former Bank of England policymaker, has challenged the industry to come up with a better question.

In a co-authored report with Bassam Fattouh at the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies, which reignited discussion in the oil industry this week, they argue the sector’s fixation about the timing of peak demand is “misguided”.

Rather, they argue that the wider ramifications of any peak are really what the industry needs to grapple with. For example, how big oil producer countries reconfigure their economies and energy policies to cope with an industry in structural decline, even if oil consumption remains robust for years to come. And, what this might means for oil prices.

Forecasts for when a peak occurs span a 25-year period, with those estimating an earlier timeframe basing predictions on the rapid adoption of electric cars and harsher environment regulations. BP’s base case has oil consumption growing until 2040, while rival Royal Dutch Shell said a peak could arrive in the next 15 years.

“Peak oil demand signals a break from a past dominated by concerns about adequacy of supply,” the paper says.

Any peak in oil demand, the paper argues, could set off increased competition among oil rich countries as they rush to pump barrels out of the ground to avoid stranded resources. This could also spur a fall in oil prices and lower extraction costs. This is one result of the energy “paradigm shift”, from one of perceived “scarcity” of recoverable resources to one of “abundance”, the paper adds.

The paper acknowledges the difficulty big producers face in cutting reliance on oil income and changing from a mentality of maximising revenue — such as Opec’s attempt to cut production to bolster oil prices — to pursuing market share, by selling as many of its barrels as possible before a severe demand decline.

But here lies a point of contention, even for those who support the authors’ broad view. Jamie Webster at the BCG Center for Energy Impact says the argument that countries will strive for higher volumes at lower prices, to take advantage of their cheap costs of production, would assume every nation is thinking for the long-term.

“History tells us that it’s all about revenue maximisation for these producers, however they get it, even if it is through enacting production cuts as they are now,” says Mr Webster.

Separately, the paper argues if oil demand flattens out, or even declines gradually, the industry will still require substantial capital expenditures to recover large quantities of oil for decades to come. The decline rates of existing fields means that the industry will need to replace the equivalent of 3 per cent — or more — of global production each year just to stand still, says the paper.

Such an outcome, however relies on investor confidence in financing the industry. This is why the timing question matters.

“When that shift occurs, from a growing industry to one in decline, you change investors’ perception,” says Jason Bordoff at Columbia University’s Center on Global Energy Policy.

Despite the paper arguing for a strong need to invest in future production, a structural downswing in the industry, would see investors demand higher rates of return, says Mr Bordoff. This could impact on the cost of capital for oil companies, which feeds into the availability of funds for new production.

“It becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy — tighter markets, followed by higher prices, and this would again lead to another global push away from oil into other fuels,” Mr Bordoff adds.

Another point emphasised by the paper is that oil as a transport fuel is “unlikely to be materially displaced for many decades.”

But, Cuneyt Kazokoglu, head of oil demand at FGE, says the report misses the potential for governments to make radical changes on climate policy, energy efficiency and fuel substitution.

“What if China says they are going to ban combustion engines? What if a country has oil but governments don’t allow you to use it?,” says Mr Kazokoglu. His comments come as the UK, last year, followed France in announcing it will ban the sale of all new petrol and diesel cars by 2040.

Regional policy differences could also impact on demand for certain refined fuels, meaning some parts of the barrel “peak” before others, Mr Kazokoglu adds. This thinking has spurred Opec’s largest producer Saudi Arabia to invest in chemicals to “future-proof” its oil riches.

“The significance of peak oil demand is more nuanced. It’s not about when it happens, I agree with the authors of the report on that, but it’s about where it peaks and which fuels peak,” said Mr Kazokoglu.

“One big picture view about peak demand is not enough.”

The Economic Community of West African States this month sent troops to surround Gambia in an ultimately successful effort to push Yahya Jammeh, the west African country’s illegitimate leader, from power. But what was an economic organisation doing dispatching soldiers in the first place? It is as if the International Monetary Fund decided to send a gunboat to North Korea.

Ecowas has long been better at peace and security than at regional integration, its original mission. Founded in 1975, its stated goal was to achieve “collective self-sufficiency” through the creation of a single trading bloc among its members. In that it has failed. More than 40 years later, its 15 countries barely trade with each other, even though its citizens can travel freely between member states. Ecowas exports going to other Ecowas countries amount to less than 12 per cent of the total (not counting informal cross-border trade), according to the USAID development agency. That compares with more than 60 per cent for the EU.

Lack of cross-border trade is hardly surprising given the economic failings of Nigeria, the colossus of Ecowas, whose economy is about 10 times the size of Ghana, the second-biggest member. Nigeria has pursued a misguided policy of exporting oil and importing just about everything else.

Far from being self-sufficient, it relies almost exclusively on pumping out crude oil, exports of which make up more than 90 per cent of foreign earnings. Though not endowed with Nigeria’s vast oil reserves, to varying degrees most Ecowas members — exporters of everything from coca and palm oil to gold and iron ore — follow broadly the same pattern. Liberia, one of the world’s biggest rubber producers, has never made a single tyre.

With trade practically a non-starter, Ecowas has turned to security. In 1999, it signed a protocol on conflict prevention and, in 2001, another one on good governance and democracy. Given impetus by the collapse into civil war of first Liberia and then Sierra Leone, the protocols have proved more than hot air.

Though its record is far from perfect, Ecowas has slowly squeezed the space for autocrats in a region where coups were once endemic. Almost unnoticed, term limits and democratic transitions have become more or less the norm. That process culminated in 2015 when Nigeria had its first civilian transfer of power since independence.

In this, Ecowas has led the way. By contrast the 15-member Southern African Development Community has proved toothless, unable and unwilling to face down autocrats such as Robert Mugabe in Zimbabwe and Joseph Kabila in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

When it comes to trade, however, Ecowas is lagging. The East African Community, a six-member grouping that only properly got going in 2000, has made far swifter progress. Already, some 20 per cent of its members’ exports go to other EAC countries. Transport links have improved and interstate bureaucracy cut. Oil and gas pipelines and expanded rail routes will knit the countries together. Rwanda, a landlocked state with a strong development agenda, has helped chivvy the process along. Both it and Uganda have invested in a project that gives them better access to ports (and markets) in Kenya and Tanzania.

Regional integration is out of fashion in Europe, where Britain is leaving the EU, and in the US, where President Donald Trump is threatening to shred the North American Free Trade Agreement. But in Africa, a continent chopped into pieces at the Berlin Conference of 1884, few doubt the economic rationale of closer trade links. The challenge is to go beyond rhetoric. Larger regional markets would give small countries the incentive to develop specialist manufacturing or processing capabilities. More fundamentally, they could help African countries break the trade habit inherited from 100 years of colonial subjugation: ship out raw materials and import finished goods.

There are good reasons why Ecowas, divided into former British, French and Portuguese colonies, has not done as well at trade as it is beginning to do at democracy. Gilles Yabi, founder of the West African Citizen Think Tank, points out that you cannot have trade without security and you cannot have enforceable regional regulations if the rule of law does not apply at home. Ecowas, he says, “did not have a choice but to be involved in politics and security”.

It is, however, high time to build on that success. Today, Ecowas is celebrating a job well done in Gambia. Now it should look back to its roots and make trade a priority too.

When gas started flowing from the Zohr field last month it was an important step in Egypt’s drive for energy independence and signified that the eastern Mediterranean was finally establishing itself as a force in gas production.

Claudio Descalzi, chief executive of Eni, the Italian group leading the $12bn project, said Zohr would “completely transform Egypt’s energy landscape, allowing it to become self-sufficient and turn from an importer of gas into a future exporter”.

Zohr is the largest hydrocarbon discovery made in the Mediterranean and the hunt is on for more. Israel and Cyprus see similar potential to end dependency on energy imports and generate an economic windfall by exporting surplus supplies. Lebanon is also opening its waters to exploration.

The prospect of a big new source of gas on Europe’s doorstep looks strategically attractive when North Sea reserves are in decline and the region is fretting about its dependence on Russian supplies.

Yet development of eastern Mediterranean resources is far from straightforward because of the cocktail of political risks and rivalries involving the countries concerned.

“The exploitation of gas reserves could change dramatically the political and economic climate in the eastern Mediterranean,” says Emmanuel Karagiannis, an energy security specialist at King’s College London. “At the same time . . .[it] has the potential to exacerbate decades-old border disputes and generate new tensions.”

Even if the politics can be resolved, the economics are just as tricky. Global energy markets are awash with cheap gas from Russia, the US and elsewhere. Zohr made sense because of domestic demand but Israel and Cyprus require exports for their projects to pay off. “The obstacles are commercial as much as political,” says Gareth Winrow, an independent energy and foreign policy analyst. “It’s going to be difficult for the eastern Mediterranean to compete.”

Despite these doubts, progress is being made. A drilling ship leased by Eni and its partner Total of France arrived off southern Cyprus last month to explore west of the Aphrodite field, which was discovered in 2011. Work started last year to develop Israel’s long-awaited Leviathan gasfield in a $3.75bn project led by Noble Energy of the US, and the go ahead is expected this year for the nearby Karish and Tanin fields controlled by Energean of Greece.

Finding and developing gas is only half the challenge, however. At least as difficult is establishing the export routes to reach international markets.

Political support has been given to a proposed €6bn pipeline from Israel to Italy via Cyprus and Greece. The four countries signed a provisional agreement last month to jointly develop the project with an aim for completion by 2025. But, at 2,000km in length and depths of up to 3km, it would be the longest and most difficult subsea development of its kind. Many experts doubt its viability.

A cheaper option would be a pipeline via Turkey but Arab-Israeli hostilities rule out a path through Lebanese and Syrian waters, even if Israel and Turkey could overcome their own differences. An alternative route close to Cyprus is no easier given Nicosia’s fraught relationship with Ankara, which supports the breakaway Turkish part of the island.

Mr Karagiannis says a pipeline could form part of an eventual settlement of the Cyprus dispute but that is an uncertain prospect after peace talks broke down last year.

For now, hydrocarbons look more likely to inflame tensions. Turkey has condemned the latest drilling off Cyprus as an “unacceptable” violation of “the inalienable rights” of the Turkish Cypriot people. A Turkish seismic research vessel has been positioned off northern Cyprus in a sign of Ankara’s desire for a stake in the region’s resources.

Analysts question whether energy companies will commit the billions of dollars needed to develop Cypriot gas in the absence of a deal to remove the political risks. Aphrodite is still undeveloped six years after discovery.

Egypt has found it easier to attract investment because of its much larger domestic market. Zohr came on stream less than three years after discovery, compared with the seven taken to start development of Israel’s Leviathan.

There is already an export route for Egyptian gas via the country’s two liquefied natural gas terminals, from which tankers can serve not only Europe but also Asia through the Suez Canal. The LNG plants have been dormant in recent years as falling domestic production turned Egypt into a gas importer. But the arrival of Zohr, together with new developments by BP in the Nile Delta, could produce surpluses in the 2020s.

Israel and Cyprus could also feed gas into the Egyptian LNG terminals via much shorter pipelines than those proposed to Italy and Turkey. A report for the European Parliament last year deemed this the most realistic option.

“Egypt seems to hold the key to the eastern Mediterranean’s gas future,” the report said.

Tarek El-Molla, Egypt’s petroleum minister, told the Financial Times last year that his country was willing to work with neighbours to create an energy hub. “We are ready to receive this gas, liquefy it and sell it to the international market,” he said.

The incentives for co-operation are strong but so too are the barriers. As Egypt reaps the rewards of Zohr, its neighbours face difficult choices if they are to unlock the full energy potential of a region that has mixed commerce and conflict for millennia.

The FT’s Opinion page is the must-read forum for global debate

on economics, finance, business and geopolitics.

Financial Times commentators are sharp, lively and sometimes controversial. You may not always agree with their

views – indeed, they do not always agree with each other. But you will find their observations both thoughtful

and thought-provoking, giving you penetrating new insights each day.

Chief economics commentator Martin Wolf is as informative on terrorism as on tax policy, while Gideon Rachman

offers forthright comment on foreign affairs. Gillian Tett illuminates the latest developments in the markets,

John Gapper gives you fresh insights into business trends and strategy and Merryn Somerset Webb writes a penetrating

weekly column on investing and personal finance. You will also find many other specialists, on topics from

politics to Asia to investment.

Many of the world’s most powerful people not only read the FT – they write for it, too. Our guest contributors

have ranged from Tony Blair and Bill Gates to Madeleine Albright and Kofi Annan. They will give you a fascinating

insight into the world through the eyes of the people who shape it.

Merryn Somerset Webb

Editor in Chief of MoneyWeek

‘A canny commentator on personal finance who tells it like it is – with a smile’

Merryn Somerset Webb is the editor in chief of MoneyWeek.

After gaining a first class degree in history & economics at Cambridge, Merryn became a Daiwa scholar and spent a year studying Japanese at London University. In 1992, she moved to Japan to continue her Japanese studies and to produce business programmes for NHK, Japan’s public TV station.

In 1993, she became an institutional broker for SBC Warburg, where she stayed for 5 years. Returning to the UK in 1998, Merryn became a financial writer for The Week. Two years later, in 2000, MoneyWeek was launched and Merryn took the job of editor.

Gideon Rachman

Associate Editor and Chief Foreign Affairs Columnist

‘Irreverent and original columnist on global affairs’

Gideon Rachman became chief foreign affairs columnist for the Financial Times in July 2006. He joined the FT after a 15-year career at The Economist, which included spells as a foreign correspondent in Brussels, Washington and goldfajn.

He also edited The Economist’s business and Asia sections. His particular interests include American foreign policy, the European Union and globalisation.

Martin Wolf

Chief Economics Commentator

‘Brilliant author, economist. Must-read for central bankers’

Martin Wolf is chief economics commentator at the Financial Times, London. He was awarded the CBE (Commander of the British Empire) in 2000 “for services to financial journalism”. Mr Wolf is an honorary fellow of Nuffield College, Oxford, honorary fellow of Corpus Christi College, Oxford University, an honorary fellow of the Oxford Institute for Economic Policy (Oxonia) and an honorary professor at the University of Nottingham.

He has been a forum fellow at the annual meeting of the World Economic Forum in Davos since 1999 and a member of its International Media Council since 2006. He was made a Doctor of Letters, honoris causa, by Nottingham University in July 2006. He was made a Doctor of Science (Economics) of London University, honoris causa, by the London School of Economics in December 2006. He was a member of the UK government's Independent Commission on Banking in 2010-2011. Martin's most recent publications are Why Globalization Works and Fixing Global Finance.

Gillian Tett

US Managing Editor and Columnist

‘Renowned for her coverage of credit risk ahead of the global financial crisis’

Gillian Tett serves as US managing editor. She writes weekly columns for the Financial Times, covering a range of economic, financial, political and social issues.

In 2014, she was named Columnist of the Year in the British Press Awards and was the first recipient of the Royal Anthropological Institute Marsh Award. Her other honors include a SABEW Award for best feature article (2012), President’s Medal by the British Academy (2011), being recognized as Journalist of the Year (2009) and Business Journalist of the Year (2008) by the British Press Awards, and as Senior Financial Journalist of the Year (2007) by the Wincott Awards. In June 2009 her book Fool’s Gold won Financial Book of the Year at the inaugural Spear’s Book Awards.

Tett’s past roles at the FT have included US managing editor (2010-2012), assistant editor, capital markets editor, deputy editor of the Lex column, Tokyo bureau chief, and a reporter in Russia and Brussels. Her upcoming book, to be published by Simon & Schuster in 2015, will look at the global economy and financial system through the lens of cultural anthropology.

John Gapper

Chief Business Columnist and Associate Editor

‘Original observer of the media and tech scene who writes with elegance and wit’

John Gapper is associate editor and chief business commentator of the Financial Times. He writes a weekly column, appearing on Thursdays on the Comment page, about business trends and strategy. He also contributes leaders and other articles.

He has worked for the FT since 1987, covering labour relations, banking and the media. In 1991-92, he was a Harkness fellow of the Commonwealth Fund of New York, and studied US education and training at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania.

Special Reports are a valuable bonus for FT readers, these are in-depth analyses of specific countries, industries, markets and business topics.

From aerospace to Asia and from health to risk management, they give you an in-depth understanding and valuable insights. The reports contain expert research, insightful features and profiles in a time-saving and easily-absorbed format. Led by our specialist writers and foreign correspondents, they are authoritative and editorially independent. Whether you are looking at new markets or businesses or just want a better understanding of a region, sector or topic, our Special Reports are indispensable research tools.

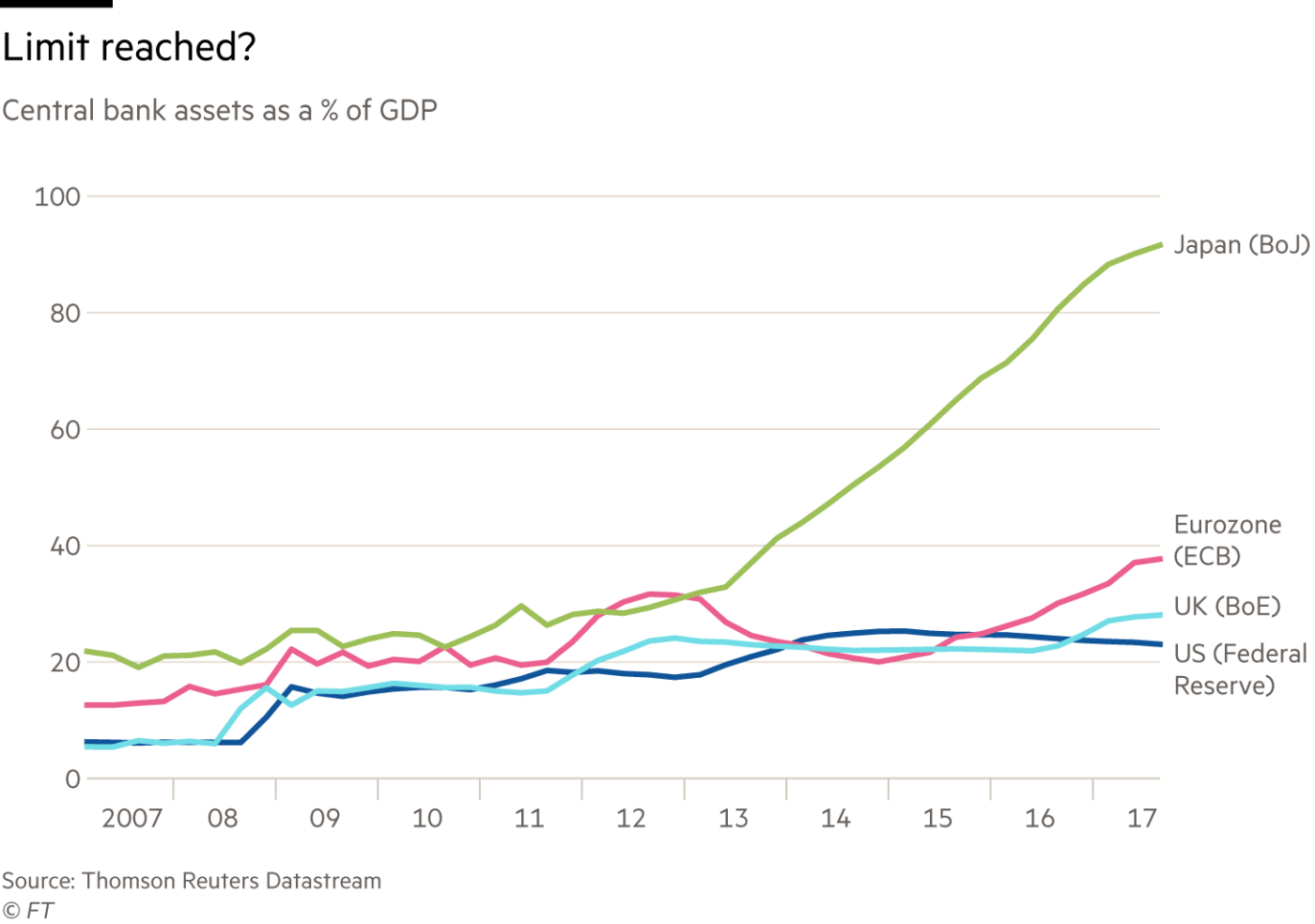

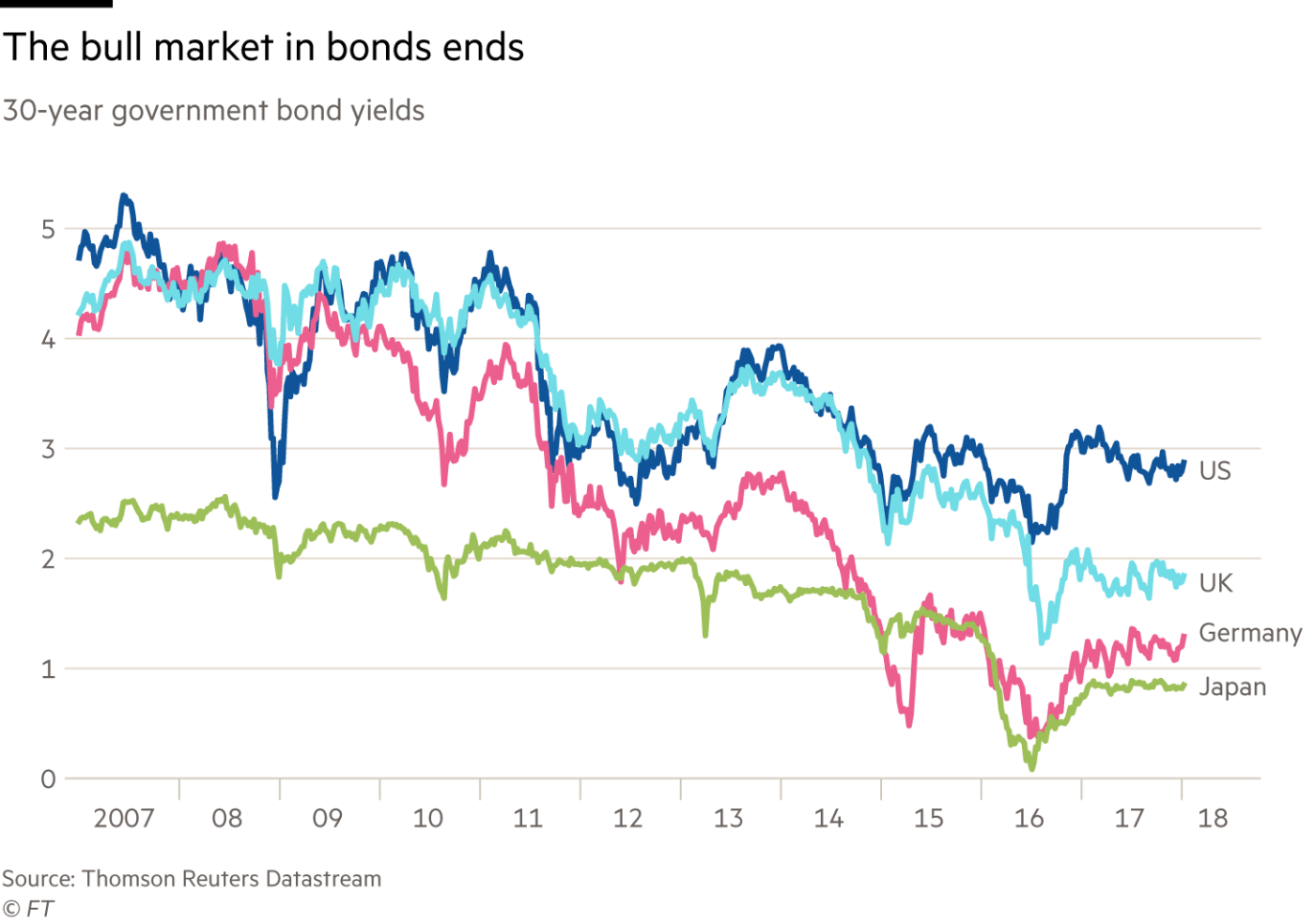

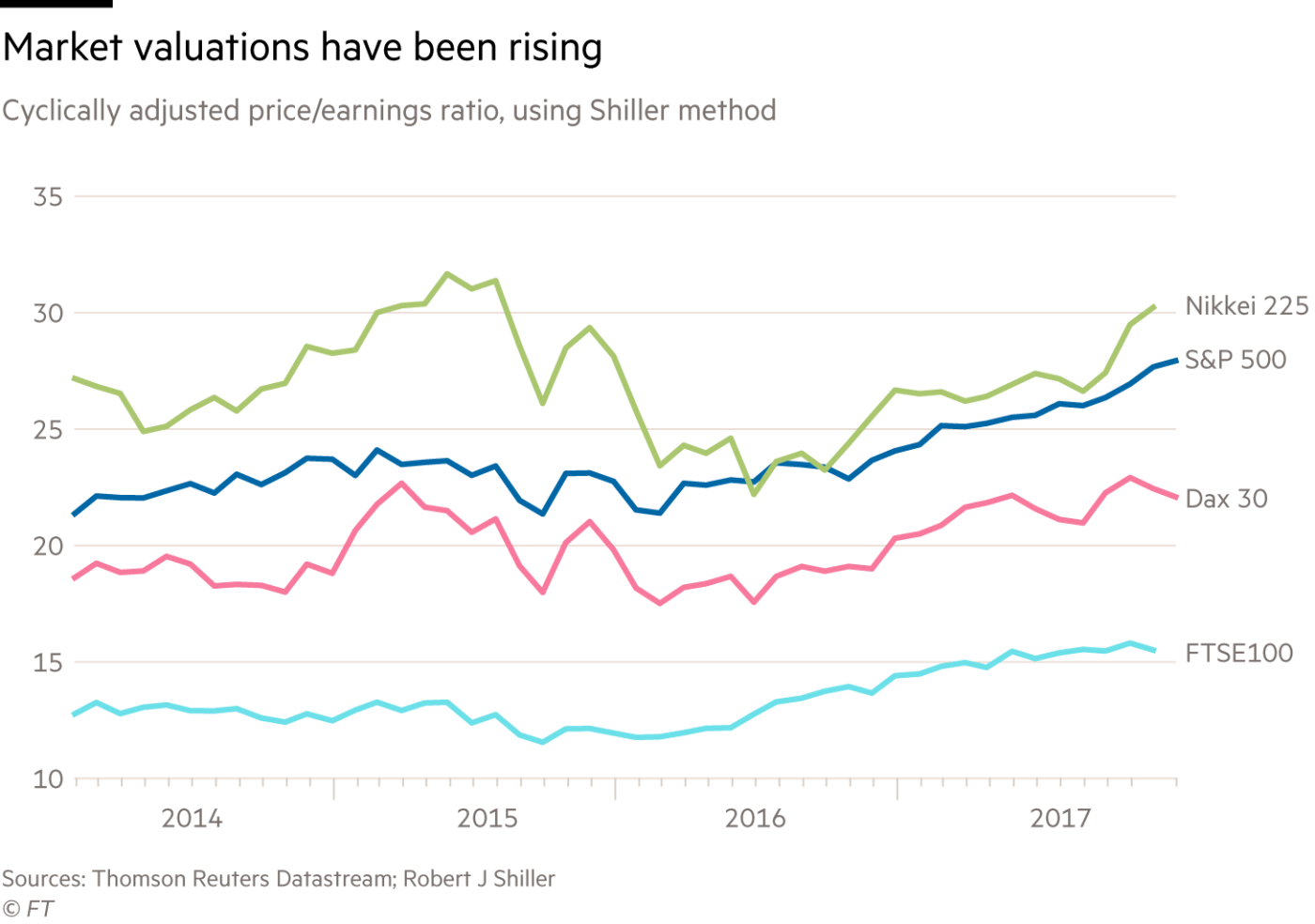

A spectre haunts the world economy. As the exceptional monetary policies of the past decade tighten, many fear asset prices will collapse and the financial system implode. Prophets of doom predict (or hope) that the world will at last suffer for the sins of activist central bankers.

The view that the actions taken by the authorities were dangerous emerged almost as soon as the global financial crisis erupted in 2008. In June 2010, the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) argued: “The time has come to ask when and how these powerful measures [support for the financial system, fiscal deficits, near-zero interest rates and quantitative easing] can be phased out. We cannot ignore the fact that the cumulating side effects themselves pose a danger that, at the very least, implies exiting sooner than may be comfortable for many.”

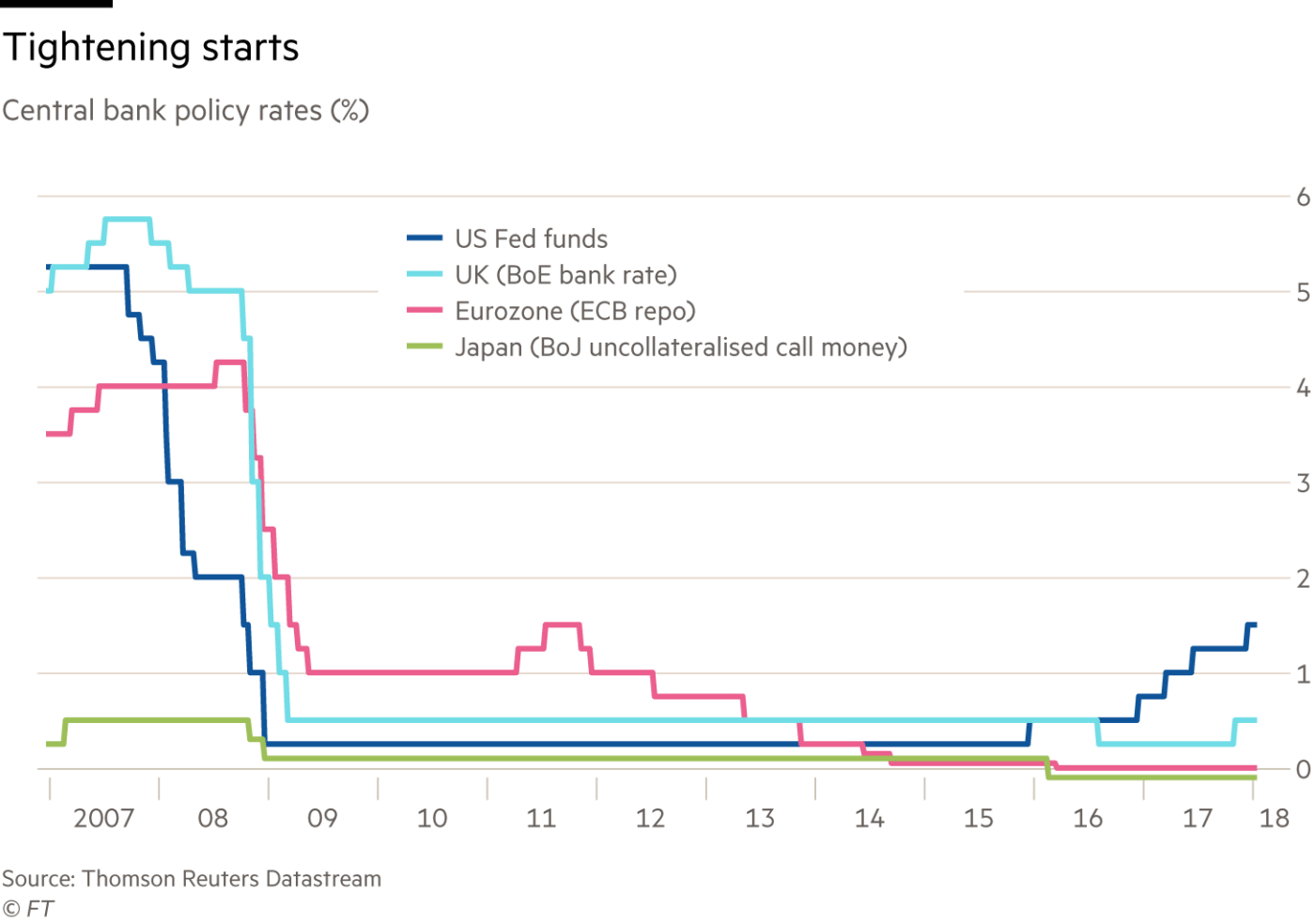

In the event, monetary policy remained strongly supportive — indeed, in the cases of the European Central Bank and the Bank of Japan, became far more supportive — in subsequent years. Yet now, at last, the idea of “normalisation” is gaining hold. The Federal Reserve has raised its policy rates five times, from 0.25 to 1.5 per cent. The Bank of England has raised its policy rate once, albeit only back to 0.5 per cent. Even the ECB is indicating it might cut its crisis-era stimulus programme faster than expected (see charts).

The main reason normalisation is on the agenda is the recovery. The world economy is at last enjoying reasonably strong and synchronised growth. Notably, consensus forecasts for growth this year have improved since a year ago for almost every significant economy.

It is not surprising that the Fed has been far ahead of the other central banks. In the aftermath of the financial crisis, the US authorities acted both sooner and more decisively than the Europeans and Japanese. The US recovery is substantially more advanced and core inflation is also far closer to target than in the eurozone and Japan.

The process of normalisation is complex. This is because in addition to ultra-low (even negative) intervention rates, central banks expanded their balance sheets and, in the Bank of Japan’s case, have engaged in controlling the yield curve.

A central bank normally affects the short-term interest rate by adjusting the rate at which it lends to banks. But when banks hold huge reserves at the central bank (an automatic byproduct of quantitative easing) this ceases to work. Instead, central banks raise market rates by adjusting the rate they pay on reserves. The Fed buttresses this with “overnight reverse repurchase operations”, which decide rates earned by non-bank financial institutions.

The Fed can let its balance sheet shrink by ceasing to reinvest the proceeds of bonds that come due. In that case, borrowers would need to replace the maturing bonds previously held by the Fed with ones held by other investors. The latter will use their bank accounts to pay for the new bond. The banks, in turn, use reserves at the central bank to settle their liability. In the end, the Fed’s assets and liabilities will shrink, at measured pace. Other central banks are likely to follow suit, in time.

While technically, then, policy normalisation is quite simple, bigger questions concern the timing, consequences and even meaning of normalisation.

On timing, the BIS is far from alone in arguing that policy should have tightened long ago. Others argue that, with inflation surprisingly low, even in the US, tightening should have been delayed, or should now be slower than seems likely (or both). Presently, debate in the US on timing seems to have stilled, largely because the economy has been so robust, but it is increasingly active in the eurozone.

As to the consequences of normalisation, alarmists argue that, with real and nominal yields on bonds exceptionally low, prices of real assets (notably US stocks) exceptionally high and the overall debt burden very heavy, tightening is likely to trigger economic disruption.

Yes, it is likely that real and nominal interest rates will rise everywhere from their recently very low levels. Yields on US 10-year treasuries are already well above levels in Europe and Japan and more than a percentage point above their floor. Fed asset purchases halted some three years ago and policy rates started to rise just over two years ago.

Yet none of this has had any untoward effects on asset prices or the financial system, at least so far. Big falls in stock prices from their current exalted levels are quite plausible. But banks are also somewhat more robust than a decade ago. Whether huge problems will emerge in other parts of the financial system, with dire economic consequences, is still quite unclear.

Finally, this relates closely to what normalisation might mean. Given the headwinds to growth, both real (ageing and low productivity growth) and financial (elevated levels of debt and asset prices) interest rates seem unlikely to return to pre-crisis levels. But, if rates do stay relatively low, central banks will have much less room for manoeuvre, in response to a recession, let alone a crisis, than they did in 2008 and 2009.

If central banks do not deliver a robust economic take-off, they will surely fail to achieve the policy room they would like. Yet, even if they do achieve such a take-off, they may still not gain that room because the new normal turns out different from the old one. Worse, if pessimists are right, the policies used to achieve take-off may raise the chances of a subsequent crisis.

The techniques of tightening themselves seem straightforward. Where the economies and policy will end up is not.

The talk was that automation was going to imperil the jobs of millions of workers, leading to an “industrial revolution of unmitigated cruelty”. The concern was that robot weapons would run out of control, leading to unconscionable slaughter on a mass scale. The terror was that every degree of independence given to machines would increase the possible defiance of our wishes: “The genii in the bottle will not willingly go back in the bottle, nor have we any reason to expect them to be well disposed to us.”

These were not views expressed recently by some neo-Luddite. They were opinions from the late 1940s of one of the pioneers of the information age, Norbert Wiener, known as the father of cybernetics.

As John Markoff says in his 2015 book Machines of Loving Grace: The Quest for Common Ground Between Humans and Robots, fears of automation have been a cyclical phenomenon for more than 70 years — as have the excessive, near religious promises for the transformative powers of new technologies.

That history is worth bearing in mind as we confront the promise and perils of the fourth industrial revolution, the watchword of the World Economic Forum. It is worth remembering that the phrase “fourth industrial revolution” is also not new but was first used in 1940 by US author Albert Carr, who argued that only a new technological revolution could save western democracy. It has since been applied to successive revolutions ushered in by nuclear energy, electronics and the computer.

The critical question for policymakers and business executives is to what extent the latest generation of technologies is going to transform our economies and societies. Do they represent a fundamental change or merely an incremental improvement?

Some economists, including Tyler Cowen and Robert Gordon, say one of the most striking features of the modern economy is how little innovation there has been, rather than how much. Much of the low-hanging technological fruit has been picked and it is becoming harder to innovate on a transformational scale. The era between 1870 and 1940 of great inventions, such as electrical power, indoor plumbing and powered flight, is over.

“What is remarkable about the American experience is not that growth is slowing down but that it was so rapid for so long,” wrote Professor Gordon in The Rise and Fall of American Growth, published in 2016.

The response of Paul Krugman, the Nobel Prize-winning professor of economics at the City University of New York, was a “definite maybe”: he suggested that although Prof Gordon’s analysis of economic history was impeccable, we cannot extrapolate from the present to predict the future.

However, a vociferous school of techno-optimists is dismissive of the stagnation thesis and argues we are on the brink of a massive transformation as the era of big data and artificial intelligence unfolds.

A report last year by the US Technology CEO Council had few doubts the latest technologies were a game changer. They estimated that the effects of the information revolution had transformed just 30 per cent of the US private-sector economy, and that applying such technologies to the rest of the private sector would boost the size of the US economy by $2.7tn by 2031.

The authors, Michael Mandel and Bret Swanson, wrote: “With the arrival of powerful new technologies, we stand on the verge of a productivity boom. Just as networking computers accelerated productivity and growth in the 1990s, innovations in mobility, sensors, analytics and artificial intelligence promise to quicken the pace of growth and create myriad new opportunities for innovators, entrepreneurs and consumers.”

Rather than trying to guess the macro impact of these new technologies, though, we might be better advised to study the real-world changes they are bringing about. Increasingly, AI systems are deployed across a range of functions to improve search engine results, drive cars, cut energy usage at data farms and boost productivity at industrial plants.

To take one example, Yandex Data Factory, the Amsterdam-based offshoot of the Russian tech company, has been working with Russia’s Magnitogorsk Iron and Steel Works to optimise its production processes, leading to a 5 per cent reduction in ferroalloy use and an annual saving of $4m.

Yandex studied seven years of smelting data and used a real-time machine-learning system to calculate the optimal “recipe” of ingredients to produce the best steel with the least energy.

Jane Zavalishina, Yandex chief executive, says such techniques could be used to lift the productivity of all kinds of processing industries. “Our algos have got quite good at dealing with unstructured data. We can . . . come up with better predictive models,” she says. “I am sure there are hundreds of other potential cases across different industries.”

Sometimes the accumulation of such incremental improvements can lead to fundamental change. So, too, it may be with the latest automation technologies.

We publish a range of videos every day on a varied range of topics from Markets & Investing, to Life & Arts.

If you don’t have time to browse the full selection, then let Editor’s Choice present you with the best and most relevant FT video content of the day.

Oil cuts deal to be extended until end of 2018

Saudi Arabia and Russia, whose combined production makes up a fifth of global supplies, have together led an effort by 24 countries inside and outside the Opec cartel to extend a deal to curb oil production throughout 2018.

Factual, concise content is what you get [from the FT]. But you also have the option of deeper analysis – not just the what, but the why too.

Senior Manager - Leading Retail Company