If your board is considering the risks associated with environmental, social and governance criteria (ESG) one question may be: “Why have we not addressed this before?”

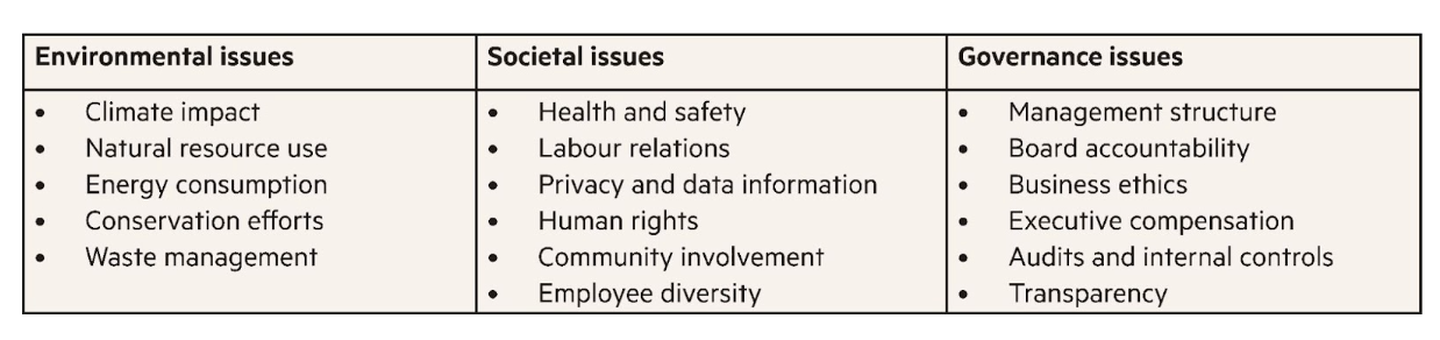

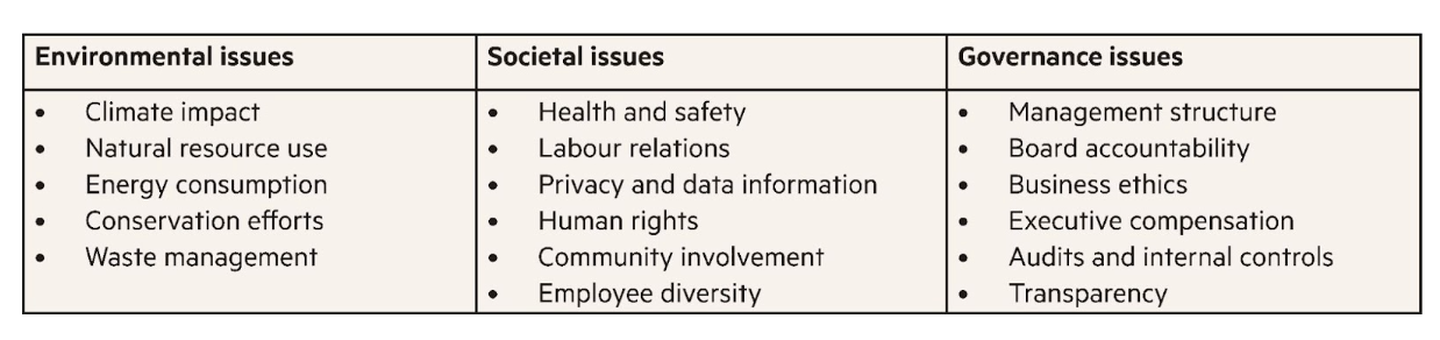

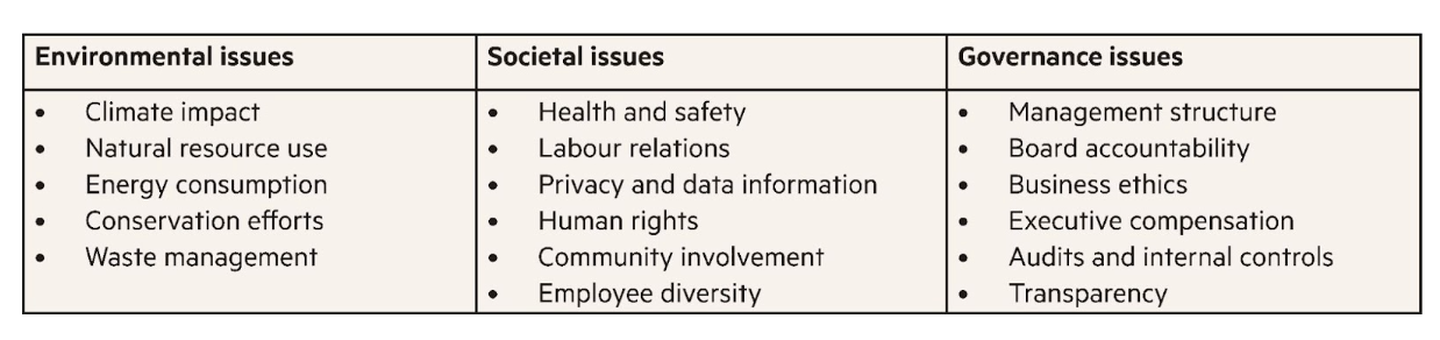

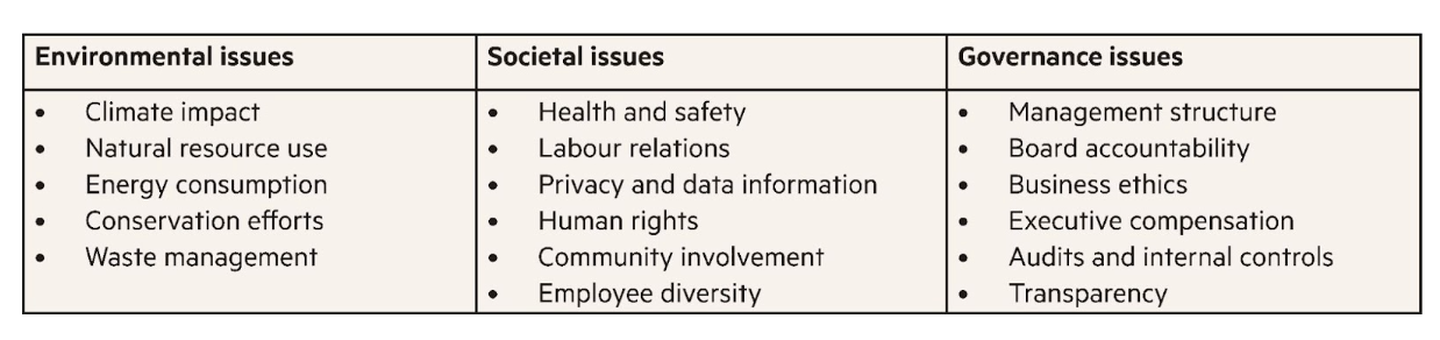

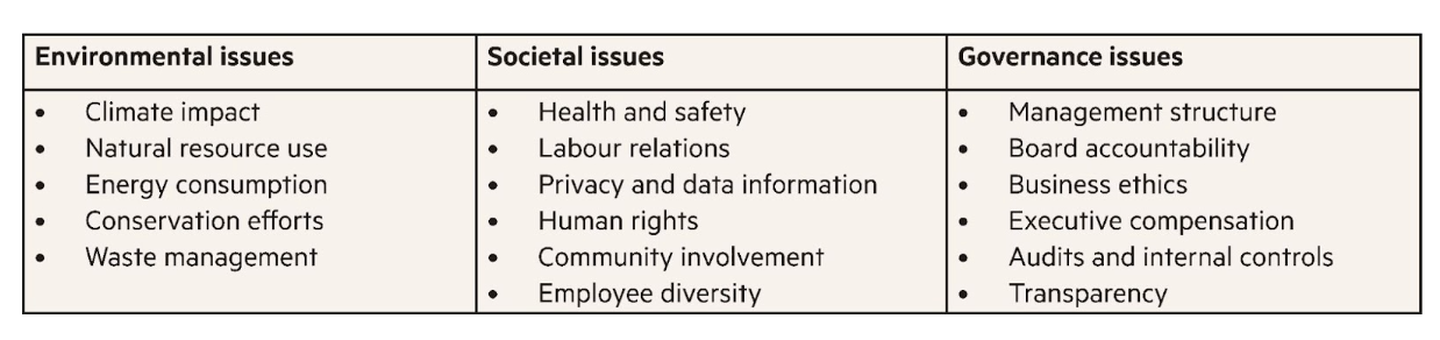

The need to create long-term value is not new. We have known about environmental issues such as sustainability for 50 years, societal and corporate responsibility for 30 years and best practice accountability, or good governance, for more than 10 years.

Now that these are fused into an investor fashion called ESG, boardrooms are under pressure to show that this is about more than planet, pollution and packaging.

The first point a board needs to understand about ESG is: “Why are we looking at this?” Has the investor relations director finally convinced the board to listen to investors? Does the head of customer relations have surveys that show dissatisfaction? Is the head of human resources worried about staff turnover?

What is the itch you are trying to scratch? Is the risk of doing nothing really greater than the risk of doing something? ESG prompts questions on risk appetite.

If you do not know what you are trying to change or improve, you risk making matters worse. One UK retailer concentrated on sustainable packaging and a host of environmental considerations that were important to the customer experience. They were proud of their work on the E of ESG. However, they overlooked equal pay between the sexes. Investors considered that the poor S rating outweighed all the good work on E.

The second issue a board needs to consider is consensus on the two fundamental axes: sustainability and responsibility.

Can directors agree on what sustainability means, and how the business can improve? Can they also agree on responsibility, for example is their first duty to shareholders or are there other critical stakeholders?

Extractive industries such as oil, gas and coal deplete finite resources and will never qualify as sustainable, but a board can act responsibly towards the local population and its employees, so it could be more important to emphasise S or G rather than E.

The third point a board has to consider is: “Is the pain worth the gain?” The cost of improving ESG performance can be overwhelming. Although the purpose is to cement long-term value, some investors will not look kindly on the share price falling in consecutive quarters.

You may lose those investors who judge you on the short-term. A new ESG strategy may mean that you lose the shareholders who don’t buy into your values. In trying to improve long-term value you jeopardise a proven model.

Steelmakers have had to be creative in sourcing nickel after the Ukraine war led to sanctions on Russia, a major supplier. Operationally a steel producer has to adapt its supply chain but investors will worry over repercussions if there is a chance of being seen to be complicit in sanctions-busting.

The fourth issue a board needs to consider is the cost of getting it wrong. Is there a forgiveness factor in the learning process?

It is possible for a company to make a few mistakes with environmental or societal issues because investor confidence or reputational damage usually erodes slowly – and can be corrected.

Conversely, any mistake with governance tends to have a sudden effect, such as the resignation of a non-executive director or being forced to issue an unforeseen profit warning. These can dent investor confidence catastrophically.

One UK wine retailer saw its share price plummet after the sudden resignation of a NED who had been appointed to the board only recently by a major investor. The director found a governance issue with which he could not risk being associated, and other investors took flight, driving down the share price by 40 per cent in days.

The final point for any board is to appreciate that ESG is an investor fashion. There is enormous granularity and no agreed measurements: you can design your strategy to suit your audience.

There are few rules and the people who have been driving ESG as a topic are those who profit from the creation and measurement of fund performance.

Some investors like to see a link with one or more of the 17 UN goals for sustainable development, but this is only a guide. Create a dialogue with investors and discover the performance measurements they value. Do not assume you know what they want. Double check that these will mean something to your business and provide strategic goals: you don’t want a distraction.

The author is Garry Honey, visiting professor at Headspring, a joint venture between the Financial Times and IE Business School.