Welcome to the Best of the Financial Times

Below you’ll find a curated selection of our award-winning journalism, showcasing a range of topical news articles, popular features as well as premium commentary and analysis that are relevant for your everyday role in your organisation.

Patrick Milne likes his gadgets. His four bedroom semi-detached house in north London has door sensors, motion sensors, smoke alarms, leak detectors and an internal camera. All of them, of course, are connected to his phone.

He got these devices for nothing: they came as part of a home insurance policy from a company called Neos, which is backed by, among others, former England footballer Gary Lineker.

The reason they were free is simple. Insurers hope they will help keep claims down and are spending money to try to encourage millions of others to follow Mr Milne’s example.

“The flood detector earned its keep after about a week,” says Mr Milne. “The boiler started dribbling water on to the floor. Within seconds the alarm went off and we got a bucket under it. Rather than a couple of grand’s worth of damage, we had a bit of mopping up to do.”

The market for “smart” internet connected home gadgets is growing rapidly, attracting some of the largest technology groups such as Google and Amazon. According to IHS Markit, the world market for connected home devices will grow from just over 100m units this year to about 600m by 2021.

But some worry that the proliferation of connected devices in the home brings its own problems, increasing, for one thing, the risk that hackers will be able to discover what people have, when they are away and even how to get through the door.

Amazon recently launched a smart lock that homeowners can use to let a courier into the house when they are out.

Neos does not yet offer smart locks. Matt Poll, the company’s founder, says market research suggests customers are not keen. “There’s a barrier,” he says. “Customers have a fear of being hacked. That’s why smart lock penetration is low.”

Apple recently had to fix a problem with its HomeKit system that could have allowed hackers to access smart locks.

Few insurers have decided how to price policies for homes secured by smart locks. “Whenever you connect a device to the internet, there is a risk they’ll be hacked,” says Leigh Calton, a former executive at insurer Ageas who now runs Cerulean Digital Consulting. “There are very few insurers who have practical experience of the data provided by these devices.”

“Insurers would probably price your policy on the basis that you do not have a [standard] five lever lock, not on the basis that you do have a smart lock.”

But insurers also want to use smart technology to change the way they relate to customers: becoming service providers rather than people who collect premiums and make payouts. Success would reduce their dependence on annual renewals.

Sean Ringsted, chief digital officer at insurer Chubb, says: “The technology will fundamentally change the relationship between insurers and homeowners. There’s a big shift from ‘repair and replace’ to ‘predict and prevent’. Now it’s not just risk transfer — the service is the product.”

Chubb is not the only one looking in this direction. In the UK, RSA and Aviva are among those working on smart home insurance. Elsewhere, State Farm, Zurich, Axa and Allianz are getting involved.

The market is also attracting start-ups. As well as Neos, there is Buzzmove, which started life helping people to move house and is now planning to introduce insurance based on connected devices. PolicyCastle, a home insurance start-up, has started offering customers a 15 per cent discount if they install a smart home security system called Cocoon.

Some industry veterans think consumers might not be so keen, though. “One thing insurers misjudge is the concept of customer engagement,” says Mr Calton. “Insurers say they’ll be able to communicate with customers on a weekly or daily basis. But why would customers want that level of contact?”

Connected homes are also susceptible to a different kind of insecurity, with privacy groups warning that people could be unthinkingly opening their doors to surveillance by large tech groups.

Matt Lehman, a managing director at consultancy Accenture, says: “Trust and privacy are a real concern . . . customers have to know how the data are going to be used. Transparency from the insurer to the customer is very important.”

Experience suggests that the roll out of smart home-enabled insurance policies could also be rather slow. “Black-box” car insurance — where insurers put a small box in the car to assess a customer’s driving and give discounts to those who drive safely — has been around for many years but has not been widely adopted.

One of the barriers there, until recently, has been the cost of the devices. The average UK car insurance policy sells for less than £500, so it does not make financial sense for insurers to supply black boxes that, until recently, cost more than £100.

A similar problem could hit smart devices for the home. “The commercial argument at the moment doesn’t stack up,” says Mr Calton.

The devices that Neos offers would sell for about £700 — well above the average £300 cost of a UK home and contents insurance policy. Mr Poll says that the company receives discounts because it buys in bulk and is relying on lower claims, costs and customer loyalty to offset the upfront cost.

Back in north London, Mr Milne says that he would be happy to stay loyal to Neos. “I think if no one comes up with a stunning deal we’ll probably stick with this,” he says. “I like techy toys but nothing too complicated. I’m very good at breaking things, and this is very difficult to break.”

Insurance companies are not known for being fleet of foot but the industry is having to catch up with the fact that customers often no longer need long-term cover in an economy where goods are rented rather than owned.

Three years ago, executives from the industry were called into 10 Downing Street to see David Cameron, then UK prime minister, who was concerned that a lack of insurance cover was holding back new rental-based business models.

Graeme Trudgill, chief executive of the British Insurance Brokers’ Association, which chaired the meeting, said that from an insurance perspective there were very different risks attached to renting compared with ownership — and that insurers did not have much data about these.

Humphrey Bowles, an entrepreneur who used to work for accommodation website onefinestay, says: “Insurance was my bugbear. Seeing hosts try to get access to insurance was ridiculous.”

Some of the industry’s bigger companies are now taking an interest in the move towards rental. Allianz organises insurance for Drivy, which allows people to hire their own cars out to others. UK insurer Admiral, meanwhile, has just launched Veygo, which allows people who do not own a car to insure themselves on other people’s cars.

For Mr Bowles, however, the problem was residential home insurance policies, which were all designed for long-term residents or landlords. None of them was designed for properties that were sometimes lived in, and sometimes rented out.

Mr Bowles now runs Guardhog, one of a number of companies trying to fill that gap. Guardhog’s home insurance is an add-on to traditional policies, covering the homeowner during periods when the property is let out.

“The idea is that we offer on-demand cover to take the uncertainty out of people [renting out] their homes. Insurance has been a big barrier that puts people off,” he said.

Property and car hire are not the only areas insurers are targeting. Others have developed policies for people who want to rent out their possessions or even their pets, or for people who want to earn some extra income with freelance jobs.

Tapoly, a start-up, is about to start offering insurance for freelance workers. Founder Janthana Kaenprakhamroy says: “They only work part-time, or only need work-related insurance for a subset of their contracts, yet the only products available to them are annual policies.”

The rollercoaster ride of the bitcoin price captivated many in the finance industry in 2018, but for Glenn Hutchins, one of the biggest establishment names to venture into the world of cryptocurrencies, this is just noise that distracts from the bigger developments that are taking place.

Mr Hutchins, the co-founder of Silver Lake Partners, a big technology-focused private equity group, is far more excited by the broader cryptocurrency ecosystem than he is by the bitcoin price smashing records.

Indeed, while Mr Hutchins has sprinkled about $5m from his family office North Island on a series of early-stage investments in companies operating in the cryptocurrency world — and is looking to invest more in the embryonic industry — he says he has yet to buy a single bitcoin himself.

“I just really think [people are] missing the point . . . They should be talking about the companies,” he says in an interview with the Financial Times. “Bitcoin could turn out to be the winner; it also could turn out to be Betamax.”

Mr Hutchins is not the biggest or earliest investor in the digital currency world. The Winklevoss twins’ bitcoin bet has now turned into a billion-dollar fortune — at least on paper — while Michael Novogratz, a former Fortress hedge fund manager, has recently become a prominent evangelist. But Mr Hutchins is arguably the most widely known, Establishment-with-a-big-E figure to take a deep dive.

The former private equity tycoon sits on the boards of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, the Brookings Institution, the Economic Club of New York, the Center for American Progress, AT&T and, until this summer, Nasdaq. He is a life member at the Council on Foreign Relations, once advised president Bill Clinton and is co-owner of the Boston Celtics basketball team. Mr Hutchins’ credibility is in contrast to bitcoin’s early popularity as a way to buy and sell narcotics.

He likens it to a railroad, where bitcoin represents the boxcar, the cryptographic bitcoin protocol is the actual rail and the blockchain — the underlying decentralised technology that underpins the digital currency — is the cargo manifest. But instead of moving barrels of paraffin, crates of apples or boxes of widgets, this ecosystem can, in theory, facilitate financial transactions instantaneously and cost-free, he says.

“It’s the biggest opportunity I’ve seen because the two most important things are business information and value. We can now move information around the world at the speed of light at no cost. Why can’t we do that with value in the future?” he asks.

Underlining the experimental, early-stage development of the cryptocurrency industry, Mr Hutchins refers to his investments as his “skunk works”, a nod to Lockheed Martin’s radical tech laboratory founded during second world war. His first foray came in early 2016, when he invested in Digital Currency Group, a venture capital firm set up by early proselyte Barry Silbert.

Mr Hutchins refers to DCG as the “bitcoin primordial soup”, and his primary gateway into other companies attempting to harness the underlying technology. DCG has invested in a further 110 digital currency-based companies. Mr Hutchins, who sits on the board of DCG, has separately invested in about 10 of these.

“It’s like every cognisable company that was coming up in the bitcoin world I got a chance to look at and understand,” he says. “What I’ve done in my mainstream career is invest in companies that use technology for a competitive advantage. That’s what I’m thinking about, I want to make sure I understand how that happens.”

Mr Hutchins points out that Levi Strauss made more money selling jeans in the Klondyke than most prospectors did from finding gold. “I’m the guy who’s thinking about building companies. Not much speculating in currency.”

Among his separate investments are Ripple, a blockchain-based cross-border payments company; Abra, a digital wallet where people can store their cryptocurrencies; Chain, which helps companies build and operate their own blockchain-based networks; and Circle, a mobile payments group.

“I’m trying to put a chip down because, if this thing works, if this thing takes off, one of these will be Google, one of these will be Amazon, one of these will be Yahoo,” he predicts.

Sceptics scoff at this kind of hype, which has become par for the course for the cryptocurrency ecosystem. Enthusiasts argue that the development of bitcoin and the host of related digital currencies are the greatest technological breakthrough since the invention of the internet. Yet the echoes of the dotcom mania are uncanny.

Simply adding blockchain to a company’s name has been enough to send shares soaring, with so far little evidence that all the excitement has led to tangible progress.

For example, bitcoin’s remarkable price rise has stirred interest, but its volatility renders it practically useless as a traditional means of exchange or store of value, the two traditional gauges of a currency, according to critics.

“It could be a bubble,” Mr Hutchins admits, saying that as a digital currency bitcoin suffers from several “serious issues”, such as how expensive and energy-intensive it is to mine.

“But the underlying companies that I’ve invested in are very serious businesses that are doing very important things, and if they get it right, have the chance to change the way we make payments around the world,” he says.

Even in the context of a global equity rally, India’s financial stocks are expensive. Valuations of the country’s banks are among the world’s highest when measured against their book values. Insurers attract similarly high premia. Yet while banks struggle with bad loans, insurers are poised to benefit from growing market share.

Insurance is a relatively new phenomenon in India, as are quoted insurers. State owned Life Insurance Corporation still dominates the market, but growth from policy renewals is slowing as consumers move to private competitors.

Three factors will determine their success. Efficiency is highest for companies that can make deals to sell policies through bank partners. Scale allows private companies to gain share in businesses that demand strong reputation, such as term life products, as well as low-risk and low-margin products such as unit linked policies.

Rising valuations have been justified by the inflow to financial savings following India’s 2016 demonetisation, a policy shock whose aftermath is beginning to ease according to government GDP forecasts released on Friday. This could, in theory, push up both stock prices and premium income for life insurers.

Robust and diverse product mixes limit risk. HDFC Standard Life Insurance Company looks best placed. Its product mix ensures high margins and it has invested in distribution, although SBI Life’s bank partnership is arguably stronger.

At a ratio of five times embedded value (an insurance-specific measure of net asset value), HDFC looks pricey compared to peers. But its value is less susceptible to fluctuations than rivals’. With a higher share of term life policies it is well placed to benefit from Indian consumers’ expanding coverage. Its return on equity of nearly a quarter beats both rivals and the puffed-up banking sector. If there is anything resembling a bargain in India’s financials, it will be found in insurance.

Australia and New Zealand Banking Group’s domestic life insurance business is following those of competitors — to the chopping block.

The group announced on Tuesday that subject to approvals Zurich Insurance would buy the unit for A$2.85bn ($2.1bn). It says this is to simplify operations and serve customers better. Shareholders should insist their interests are served too.

Together with a related sale two months ago, Tuesday’s disposal should boost the group’s capital ratio by around 80 basis points. The insurance unit’s return on net tangible assets is a third below the group return of 12.45 per cent, so it is an obvious drag on profitability. Competitors already have come to similar conclusions about their domestic life operations.

The question is what to do with the proceeds. Chief executive Shayne Elliott has hinted at capital returns, but not promised them. Two out of three options for using the proceeds are unlikely to improve value for shareholders. Buying back shares valued at 1.5 times book value would dilute earnings, given that the insurance unit is being sold for less than book value. And, as CLSA analysts point out, reinvesting in the core business brings other problems.

Loan loss charges at ANZ exceed those of peers, as do impaired loans arising from new business. ANZ is growing its loan book by buying market share. If loan losses increase to what CLSA estimates to be the average for the mid-point of the credit cycle, earnings could fall up to 12 per cent from their year to June 2018 level.

Simply returning the cash to shareholders would be unimaginative, but would also be neutral for returns on equity. Investing in the core business is only worth it if returns are lifted to peer-group levels. Mr Elliott appears to understand this. The deal will complete by the end of 2018. That gives him a year to convince investors of a viable plan. If he fails to do so, they should demand he hand over the cash.

The investors are now investees. Ping An has emerged as the third-largest shareholder in HSBC. An institution known in Hong Kong simply as “the Bank”, HSBC owned a stake in the insurer until it sold out to a Thai conglomerate in 2013. Now Ping An is the buyer, hoping HSBC’s 5 per cent dividend yield will feed a portfolio held to meet long-term liabilities.

As China’s institutions recycle the country’s vast savings, the old grandees of finance will have to get used to such reversals. Growth of the country’s insurance sector in particular shows no sign of stopping. The main question for investors eyeing Ping An’s meteoric rise this year is simply how much further it might run.

Shares in Ping An, based in China’s technology hub Shenzhen, have doubled on the back of this year’s tech stock boom. It aims to differentiate itself from competitors with its tech savvy. Between them, AIA and Ping An account for a fifth of the gain in Hong Kong’s benchmark Hang Seng index this year. This contribution has been obscured only by the stunning rise for shares of technology group Tencent.

The reasons have more to do with old world development, however, which make Asia’s developing markets a fertile ground for life insurers. Analysts at Nomura expect life insurance premia in China to grow 15 per cent a year in each of the next five years. Growing disposable income, an ageing population, low state welfare benefits and little existing private coverage support their view. Insurance contributions relative to the population size are as low as Japan’s in the late 1970s. Profits at Ping An (a life insurer) and rival AIA (which also offers property and casualty cover) have grown 25 per cent a year, for five years running.

Such growth does not come cheap. The Shenzhen group’s market value is 1.5 times its actuarial embedded value — a measure of net assets and likely future premium income. Yet it is at least less than AIA’s two times valuation, suggesting that Ping An’s rally may have further to run. China’s excess savings, meanwhile, will quietly rewire who owns whom.

One of the most complex professions in the world is at risk of being replaced. By a selfie.

Selling life insurance has traditionally involved an in-depth assessment of the customer by a qualified underwriter using a well-worn set of actuarial models. Not any longer. Lapetus, a US-based start-up, believes a selfie can replace much of that. Customers email their finest self-portraits and the computers do the rest, scanning the picture and analysing thousands of different regions of the face.

They are looking not just for basic information such as gender but for clues about how quickly the person is ageing, their body mass index and whether they smoke. Armed with this and other information from customers, the computers come up with what Lapetus says is a far more accurate prediction of life expectancy than traditional methods can provide. And the whole process takes only a few minutes.

No wonder the insurance industry is worried about the advance of technology and the potential for artificial intelligence to revolutionise the way it works. Last week about 150 young insurance professionals attended a presentation in London entitled, “Our Industrial Revolution: What does it mean for us?”.

They are not the only ones fretting about the future. At Berkshire Hathaway’s annual get-together in Nebraska this month, Warren Buffett warned about the risk of disruption to insurance from AI, in the shape of driverless cars.

“We’ve been going backwards and forwards on AI for 15 to 20 years, but I believe we’re at a tipping point because of the advancement of algorithms, storage in the cloud and computing power,” says Nick Daffan, chief information officer at Verisk Analytics, a data analysis firm.

This provides opportunities for the industry to improve the way it works, but there are also dangers — and not just that industry specialists will be replaced by machines as algorithms become more powerful. In the long run, the bigger challenge is that machines could undermine the industry by giving customers better tools to decide whether insurance is even necessary.

Data analysis is nothing new in insurance, an industry built on the use of statistics to assess risk. But AI expands the amount of data that can be analysed and the way it can be used.

Tech-savvy insurance start-ups are already circling. They see an old-fashioned industry, bloated on fat profits made in the past and complacent about the scale of change required. Some are aiming to work with insurance companies to develop new techniques, but others want to disrupt the industry and grab a slice of the market.

At a recent ceremony in London’s O2 arena, 11 insurance start-ups backed by an organisation called Startupbootcamp pitched their plans to potential investors and customers. Nine of them were basing their business plans on some form of AI or machine learning. They included Aerobotics, which is applying AI to aerial photos of farms to help provide crop insurance, and Emerge, which uses machine learning to help insurers improve efficiency.

Four areas AI could change:

1. Life insurance

Lapetus promises to use facial recognition technology to discover how healthy you are using a selfie. Another potential avenue for the industry is using social media profiles to predict lifestyle habits and risks. But there is controversy over whether genetic data will eventually be used in pricing life and health insurance.

“The start-ups are showing what is possible and what can be done,” says Henrik Naujoks, a partner at Bain & Co, a management consultancy. “A lot of incumbent executives are looking at it — they don’t really understand it but they want to get involved.”

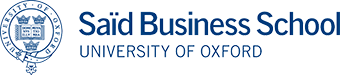

Investors are keen for a piece of the action. According to Accenture, AI was one of the most popular themes in insurance tech investment in 2016, capturing more than $500m of funds.

“The view that AI can have a near-term impact is starting to pick up,” says John Cusano, global head of Accenture’s insurance practice. “Insurance is still a very manual experience.”

***

For now, the impact of AI in insurance has been minimal. “It is definitely a disruptive force, but you could count on the fingers of one hand the number of insurers who have implemented it at scale,” says Nigel Walsh, a partner at Deloitte.

Insurers say that, at the moment, AI is a tool that helps them rather than a disruptive threat. Those using AI are focusing on upgrading their data-processing capabilities, or improving the way that they communicate with customers by using chatbots.

UK insurer Aviva is experimenting with AI. “At its most basic, we absolutely use robots and AI,” says Andrew Brem, Aviva’s chief digital officer. “In our administration teams, there are lots of repetitive tasks which until now were done by humans. Algorithms are typically 15 times more productive.”

Claims handling is another area attracting interest. Insurers say that AI can improve claims processing and help to spot fraud. Japanese insurer Fukoku Mutual Life has started to use an AI system developed by IBM in its claims department, while McKinsey forecasts that between 2015 and 2025 some western European insurers will cut up to a quarter of their staff as automation takes hold.

2. Agricultural insurance

Use of drone technology is revolutionising crop insurance. The start-up Aerobotics says it can map terrain in 3D and check plant health from the air. Use of big data in combination with mapping technologies can also be used to look at issues such as flood risk.

Mr Brem at Aviva admits that the real excitement lies elsewhere. “The interesting area is using data to predict risks better, for example using data to better predict medical risks. We look for relationships that traditional techniques would not necessarily pick up,” he says.

This is where AI and big data are expected to shake insurance up: not in processing and customer service, but in core skills such as underwriting, where the insurers assess — and price — each customer’s risk.

“Where we see machine learning changing the industry is in how the world models and understands risk,” says Henry Burton, who runs Artelligen, a start-up aiming to bring AI into commercial insurance.

Computers, so the argument goes, will be much better than human underwriters at analysing the vast amount of new data created each day. “Without question, machine learning will replace statistical models. The amount of data we create is astonishing. Driverless cars create four terabytes a day of data. Statistical models cannot handle that amount of data,” Mr Burton says.

Last year Admiral, a UK-based car insurer, experimented with using the language in Facebook posts to make predictions about driving behaviour. Excessive use of exclamation marks, for example, could suggest overconfidence.

Facebook got cold feet at the last minute and the project was pulled, but Admiral will not be the last insurer to look for predictive patterns in new and unexpected places. Armed with this vast array of data, experts say computers will be able to assess in far more detail how risky each customer is, and how much they should be charged.

The trends are enough to make human underwriters nervous. Oxford university has published a study of which professions are most susceptible to automation. It examined 702 jobs, asking machine learning and robotics experts to analyse the tasks involved in each one. Insurance underwriting was very near the top of the list, with only four professions seen as more at risk (telemarketers took the top slot).

Underwriters may turn out to be more resilient than that study suggests. Christos Mitas, vice-president of model development at data analytics group RMS, says: “We have not reached the point where it is totally automated. We have not reached an unsupervised state where the algorithm works for itself — it still needs supervision.”

3. Motor insurance

Driverless cars could revolutionise the sector by removing human error and thus cutting accidents. Meanwhile big data and telematics are helping to spot fraudulent claims. Plans to analyse social media to work out who is more prone to risky behaviour have been rejected so far

“The human element will need to be there for the foreseeable future,” he adds. “You need to train the algorithm — what data do you give it? What constraints do you give it? Transparency is important and we need to know why the algorithm behaves the way it does.”

Brian Modesitt, a managing director at Two Sigma, the computer-driven investment manager, says: “In some markets insurance is more bespoke so artificial intelligence will be more of an enabler. Machines won’t replace people everywhere. Some things are too complicated.”

Regulation will also be a factor — insurers have to be able to explain the pricing of policies to their customers. “The computer says so” is not an acceptable answer, the regulators insist.

***

That might provide comfort to worried insurers. At last week’s young professionals event in London, there was a consensus that their jobs would change, rather than disappear entirely.

More concerning for them is the risk that customers take matters into their own hands. The question of whether machines or humans do the underwriting is irrelevant if the clients decide that they do not need their product at all.

And AI could lead to just that as companies develop their own tools to analyse risk. “Where this will have an impact is on the amount of insurance that people buy and the type they buy,” Mr Burton says. “We see this as an opportunity not just to enable insurance companies to build predictive and preventive risk models but to allow businesses to have them as well. If they can model the risk in that way, they can decide what to retain on their own balance sheets and what to transfer [to insurers].”

4: The overall industry

The use of algorithms and big data sets is cutting the number of people the insurance industry needs to employ. Chatbots are being used to take customers through applications. Data analysis and AI can spot fraud patterns quickly

“The promise of AI is quite exciting,” says Deloitte’s Mr Walsh. “In underwriting, you get to a situation where you could create unique policies for each person. It is a different business model if you assess risk person by person.”

This is not science fiction. Driverless cars are one example of how the trend could make a huge difference to the industry. Carmakers, software providers and insurers will collect data from autonomous cars and use it to assess how risky those vehicles are and how much insurance will be needed. The important question is which organisation has the data and the ability to analyse it, and that will not necessarily be the insurers.

“All of a sudden I can have data about risk exposure for a set of cars which is more than any single insurer would have,” says Mr Daffan at Verisk.

Autonomous, a stockbroker, predicts that driverless vehicles will be so successful at reducing accidents that motor insurance premiums in the UK will drop 63 per cent between 2015 and 2060.

Autonomous cars are not the only example of where this could make a big difference to insurance buying. The internet of things, where everyday objects are connected to the web, means everybody will have access to more data about the sort of risks they face. These range from householders monitoring the chance of a leaky pipe to companies analysing their IT networks. If they can better predict problems and fix them before they occur, they can reduce the amount of insurance they need.

Mr Mitas is sceptical about how far that will stretch. “I don’t think we’ll have algorithms sold to insurance buyers,” he says. “You need people who understand the data and the algorithms. You need experts in model building. It’s not just about having the data, it is also about knowing how to use it.”

In any case, say industry participants, AI will not make risks disappear entirely and people will always want to protect themselves against the unexpected. The recent global WannaCry cyber attack, for example, could boost demand for cyber insurance.

“The bespoke risks in society will never go away as there is always innovation in the economy,” says Trevor Maynard, head of innovation at Lloyd’s. “Providing underwriters embrace the new technology they have a very strong future.”

Using the data

The growing use of artificial intelligence does not just create technological challenges for insurers, it creates moral and ethical questions. Traditionally, insurance has been built on the concept of pooling: insurers put large groups of similar people together in a pool. In any given year, some will need a payout while others will not. As long as there is enough money in the pool, the system works for everyone.

AI and big data break that down though. “Insurance is like a bicycle,” says Duncan Minty, a consultant on ethical issues in insurance. “Big data puts a rocket on that bicycle, and the risk is that it gets wobbly. The difficult thing is the extent to which there are unintended consequences.”

By giving insurers more information about each person and their individual risks, AI and big data allow far more accurate pricing. Risky people pay higher premiums; safer people pay less. The need to pool broad groups of similar people disappears.

The problems arise where risks are not preventable or easily avoided, such as floods. Insurers have become much better at predicting which houses are likely to be flooded, and so charge the owners of those properties huge premiums. As home insurance became unaffordable for some people, the UK government created Flood Re, which forces homeowners across the country to subsidise insurance for people in flood-prone areas.

Industry experts say the use of AI could change other types of cover in the same way as flood insurance.

More serious is the question of the use of genetic data in life and health insurance. Advanced analytics could allow insurers to price products based on each customer’s genetic make-up. The result, say critics, is that some people will be priced out of the market because of their genes. For that reason, use of genetic data by insurers is banned in most countries.

However, those curbs might not last. “If customers can use their own genetic data then eventually insurers will have to be allowed to use it too,” says Paul Sharma of consultants Alvarez & Marsal. “Otherwise they will be at a disadvantage.”

Britain’s biggest life assurers have gained billions of pounds of new business as a result of contentious pensions reforms.

In the past two years, about £50bn has been released from corporate pension schemes as tens of thousands of people swap their guaranteed retirement income for a lump sum, according to Mercer, the consultants.

One pensions administrator, Broadstone, said that Standard Life Aberdeen, Royal London, Prudential and Aviva had been among the biggest beneficiaries of the pension transfers it has processed.

Standard Life Aberdeen is one of the few companies to disclose details about the amount of money it is taking in from defined benefit transfers.

In the first half of this year, Standard Life took in about £900m to its drawdown products from the transfers. Standard Life completed its merger with Aberdeen Asset Management in August.

Aviva’s platform business, which allows customers to hold several financial products in the same place, took in about £750m from defined benefit transfers in the same period.

Other companies do not provide similar breakdowns, but their wider pensions businesses are clearly booming.

Royal London’s overall sales of individual pensions and drawdown products jumped 64 per cent in the first half of the year. At Prudential, drawdown sales were up about 30 per cent, while LV’s overall pensions business grew by a similar amount.

Earlier this week, St James’s Place reported £5bn of inflows into its pension business in the first nine months of the year.

A combination of new freedoms on how people spend their pension savings and a sharp rise in transfer values for those in defined benefit plans has led to a boom in transfers, which regulators worry is creating the potential for a new financial mis-selling crisis.

The Financial Conduct Authority is investigating whether independent financial advisers are giving suitable advice on transfers, where savers swap monthly payments guaranteed for life for a lump sum which they then invest in a personal pension plan.

The parliamentary work and pensions committee is also planning an investigation.

The transfers are a lucrative source of long-term income for assurers, which have suffered as sales of traditional pension products, such as annuities, have shrivelled in recent years.

Putting £500,000 into a Standard Life Self-Invested Personal Pension (Sipp) for 20 years, for example, would generate £38,000 in accumulated charges.

“If you get the money, you have 20 years of fees coming through,” said David Brooks at Broadstone.

As a result, the assurers have not been shy in helping financial advisers who provide guidance to pension scheme members.

Commission payments to advisers have been banned since 2013, but the insurers are doing what they can to assist them.

Some companies, including Prudential and Standard Life, pay for valuation reports, called TVAS, which are a vital part of the transfer advice process. These reports can cost hundreds of pounds if bought independently.

Other companies provide advisers with useful information. Scottish Widows, for example, has a dedicated pension transfer website, giving advisers guidance on how the transfers work.

“I see a lot of providers commenting on transfers, providing articles and assistance,” said Mike Morrison, head of platform technical at AJ Bell.

But Alistair Cunningham, financial planning director with Wingate Financial Planning, said the “increasing number of insurers offering training and marketing material is concerning, particularly as some is not as impartial as I would hope”.

“Insurers seem in a unique position where they gain custodian fees for assets transferred on, but may well try to shrug off any responsibility where the advice fails subsequent suitability tests,” he added.

However, assurers say the guidance they provide gives them comfort that advisers are giving good advice.

“We provide a lot of ammunition to help advisers reach the right decision, so we don’t have the same concerns that we might do otherwise,” said Vince Smith-Hughes, head of pensions business development at Prudential.

Ned Cazalet, head of Cazalet Consulting, said assurers were aware of the risks associated with transfers.

“Over the last 30 years, the words life insurance and mis-selling have gone together like horse and carriage,” he said. “The memories of mis-selling have not gone away and the industry has had to pay millions in redress. This is an area where people are treading gingerly.”

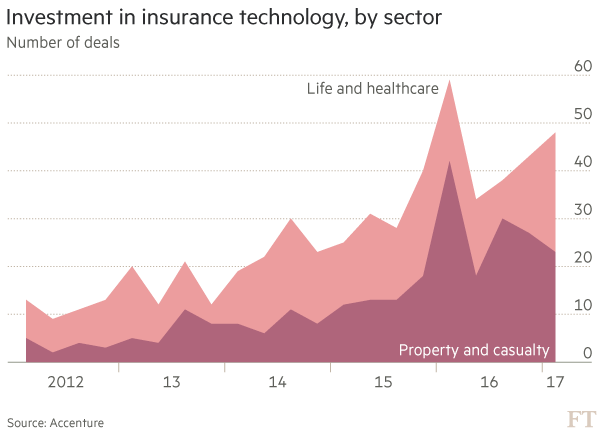

European regulators late on Tuesday abruptly delayed the introduction of Mifid II rules that form a key part of their push for greater transparency in share market trading.

The sudden development means that share trading across the region will be spared from a shake-up for at least three months, and one that was set to temporarily bar a large number of stocks from being transacted in private venues, known as dark pools.

The European Securities and Markets Authority said it had delayed publication of equities that would be excluded from being transacted via dark pools because a large proportion of trading venues had yet to provide complete data.

Hundreds of European blue-chip stocks were likely to have been caught under the new rules, which aim to limit the amount of business that takes place in dark pools, with the intention of boosting trading on public exchanges.

Publishing the calculations would have resulted in “a biased picture covering only a very limited number of instruments and markets”, Esma said.

The rulings were due to be the first calculations for Mifid II rules aimed at clamping down on the amount of trading in dark pools, where prices are disclosed only after a trade has been completed.

Under Mifid II, dark pools face a twin volume cap. Over a rolling 12-month period, just 4 per cent of the total trading in an individual stock can occur in any one dark pool.

At the same time, trading of any stock across dark pools is limited to 8 per cent of total volume. A breach of either means trading in that security is prohibited for the next six months — either from the individual dark pool that breached the cap, or from all dark pools.

The ban had been due to take effect on Friday morning.

“I suspect that regulators are going to learn that it’s one thing to mandate that everyone reports to them but another to make sense out of everything they get,” said Steve Grob, head of strategy at Fidessa, a trading technology group.

Dark pools have grown popular with fund managers reluctant to sell or buy large blocks of shares via a public stock market, as that can alert other investors of their intentions and push the price against them.

But regulators are concerned that they cannot monitor activity as easily as trading on exchanges and the industry has been tarnished in the US by high-profile punishments for infractions. Regulators have also flagged that some dark pool operators had inadequate controls to prevent potential conflicts of interest.

Esma said that, while it had received files from three-quarters of trading venues, they contained complete data from only 650 instruments or about 2 per cent of the expected total. It had hoped to publish the data in March.

Trading venues had just a few days from the end of 2018 in which to submit the data. Cboe Europe, the largest pan-European exchange, said it complied but it was now unclear how the volume caps would be implemented retrospectively. “We will work closely with the FCA and Esma on this matter,” it said in a statement.

Industry analysts had expected London to be particularly hit by the caps. The majority of daily equity trading in Europe takes place in the UK, home to the London Stock Exchange and Cboe Europe, as well as a dozen alternative trading venues and dark pools.

Rebecca Healey, head of Emea market structure at equities trading venue Liquidnet, said there was little indication the caps would have stopped shares from being traded off-exchange because traders were already seeking out alternatives that are not subject to limits.

“It’s frustrating for the industry but it’s better that Esma resets, as the volumes caps were unlikely to meet the objectives of the European politicians,” she said.

Special Reports are a valuable bonus for FT readers, these are in-depth analyses of specific countries, industries, markets and business topics.

From aerospace to Asia and from health to risk management, they give you an in-depth understanding and valuable insights. The reports contain expert research, insightful features and profiles in a time-saving and easily-absorbed format. Led by our specialist writers and foreign correspondents, they are authoritative and editorially independent. Whether you are looking at new markets or businesses or just want a better understanding of a region, sector or topic, our Special Reports are indispensable research tools.

- Although China has achieved nominal universal healthcare, the state offering is too underfunded and too overburdened to meet the growing demands of urban consumers.

- We expect premiums to recover in 2018 after the collapse in sales growth on the back of a wider crackdown on abuses in the domestic insurance industry.

China may have achieved nominal universal healthcare coverage but the chronic inadequacies of the state system, coupled with rising incomes, are driving urban consumers towards private insurers.

Among the 2,000 consumers nationwide surveyed by FTCR, 21.7 per cent said they had some private cover in addition to the state programmes (see chart).

Coverage was greatest among high-income households — 42.5 per cent of this group said they were privately covered — and among residents of first-tier cities, where 25.8 per cent of respondents said they paid, versus 17.4 per cent in third-tier cities.

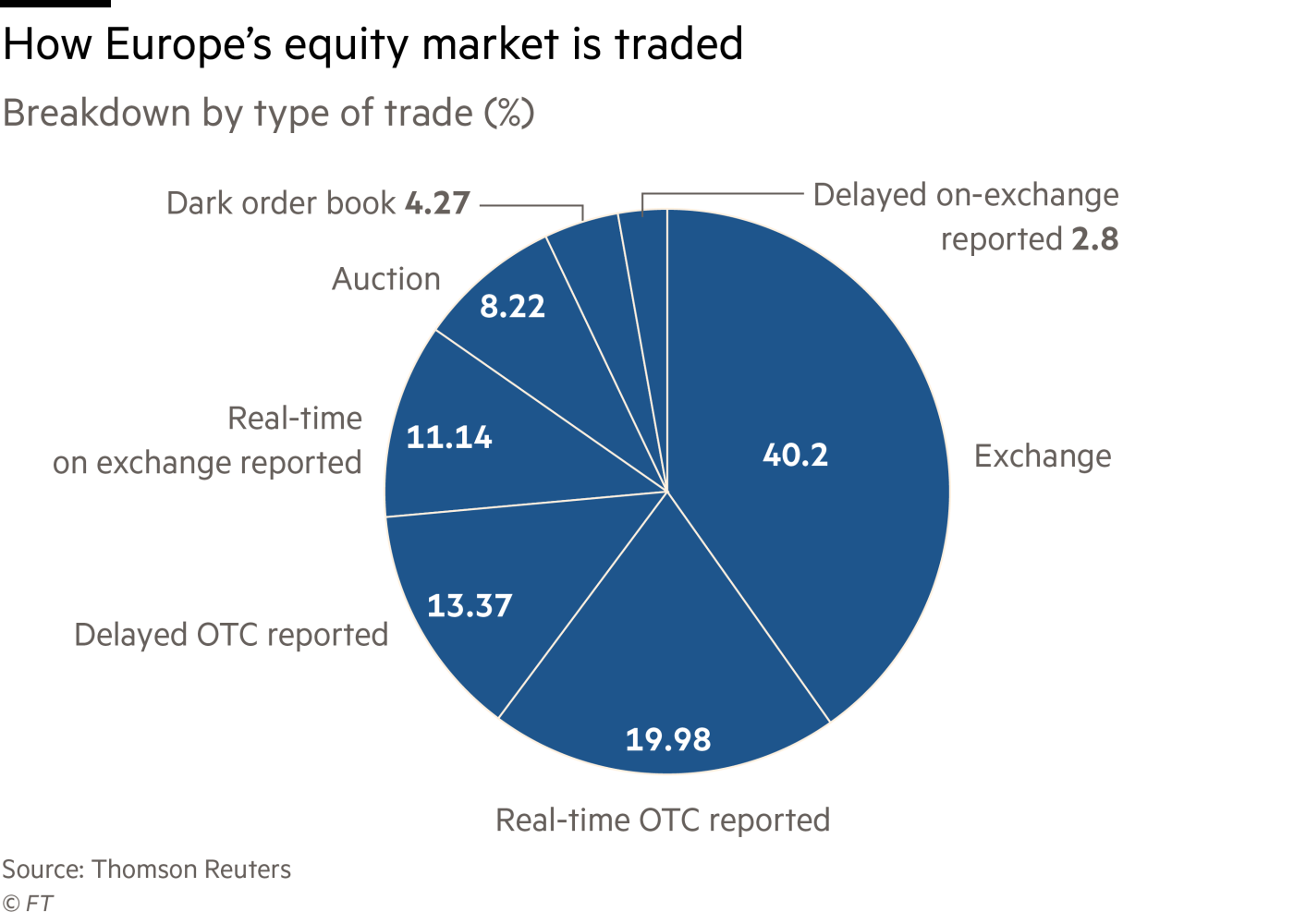

Official data show that sales growth fell sharply this year as a result of a crackdown on policies with investment components, used by insurers to leverage asset purchases at home and abroad. Sales of health insurance premiums surged 67.7 per cent last year to Rmb404.2bn ($60.9bn), partially inflated by this business, but growth slowed to just 3 per cent in the year to August 2018.

However, we believe premiums are poised to return to faster growth as the government forces the industry to get back to the business of insuring. We expect premiums to rise by around 30 per cent next year (see chart).

Insurers around the country told FTCR that sales of health policies have been brisk this year, despite the restriction on sales of investment-linked policies. Zhang Lei, a manager with the Chengdu branch of Ping An, China’s largest health insurance provider, said sales have risen by more than 80 per cent a year for the past two years.

Among urban respondents with private cover, 43.5 per cent said they pay directly (see chart). In the US, by comparison, just 16.2 per cent buy directly. Chinese employers already pay a low percentage of employee salaries into the state programme and are loath to pick up the additional cost of private cover. Although more companies are expected to offer cover to win or retain talent — Starbucks this year extended coverage to the parents of its mainland employees, for example — we expect self-financed premiums to remain the big driver of growth.

A shallow system

In 2011, the Chinese government said it achieved universal healthcare, with more than 95 per cent of the population covered by at least one of three programmes. Public spending on healthcare was ramped up following the outbreak of Sars virus in 2003, but the state offering is as shallow as it is broad (see charts).

The public system requires either large co-payments or excludes more expensive drugs and treatments altogether. We estimate the Urban Employee Basic Medical Insurance, the best funded of the three programmes, covers just 65 per cent of medical costs, while Beijing Normal University estimates the state programmes cover just 40 per cent of costs related to treating children’s leukaemia.

When Wuhan native Zhuang Longzhang’s six-year-old son Yumin was diagnosed with acute leukaemia, the state agreed to cover just 30 per cent of the family’s first Rmb15,000 bill. After a year, co-payments totalled Rmb100,000 — equivalent to 18 months of the Zhuangs’ household income. Mr Zhuang wound up borrowing from friends to make payments. His son was given the all-clear earlier this year but Mr Zhuang still owes more than Rmb200,000.

The government recognises the inadequacies of its system. In 2015, the State Council set a plan for the government to cover at least 50 per cent of the expenses related to critical illness. However, funding has fallen short as more advanced but costly treatments are developed. In Xi’an, the capital of Shaanxi province, for example, just 49 per cent of urban areas and 41 per cent of rural areas are covered by this increased critical illness cover, even though the city’s insurance fund is already running at a loss.

Hospitals are the front line of Chinese medical treatment. The top-rated hospitals are clustered in China’s biggest urban centres, so patients bypass local options — losing state insurance coverage in the process — resulting in overcrowding and brisk consultations.

Most respondents to our survey said they bought commercial health insurance to guarantee more complete coverage versus factors such as the level of service on offer or the availability of consultants. Most private plans cover at least 90 per cent of the costs for treating critical illness, while some cover overseas inpatient treatment. In contrast, the state programmes are intended to cover 70 per cent of critical illness costs, although the experience of Zhuang Yumin shows how short they can fall. Among respondents to our survey with private plans, 37.3 per cent said they intend to purchase additional critical illness cover in the coming 12 months.

Regulatory regime change

A 2016 World Bank-Chinese government study warned that, without adequate reforms, official spending on health could nearly double to more than 9 per cent of GDP by 2035, an increase the country will struggle to meet as the economy slows.

As China ages, the government has recognised the role private health insurance can play in taking the strain off state funding. The government this year allowed tax deductions of up to Rmb2,400 on employer-provided health cover, a small but meaningful step to get more workers covered.

Regime change at the insurance regulator will also encourage the take-up of commercial health cover. The commission’s chairman was sacked this year after the speculative excesses wrought by his attempts to open the industry up to private domestic firms. The commission met with foreign insurers in September and pledged to open the market up further, which could mean equity ownership caps are lifted, along with other rules on how these providers are permitted to operate in China.

This will not immediately challenge the overwhelming dominance of the state-owned giants (see chart), but greater engagement signals the government’s eagerness to deepen and broaden the health insurance market.

- Trust lending has surged in the first half of 2018 on the back of increased demand for credit from developers, companies in overcapacity industries and local government firms reeling from the bond market sell-off.

- We suspect the growth reflects banks withdrawing their business from less regulated parts of the shadow finance system and channelling it back through the trust sector, under the oversight of the China Banking Regulatory Committee (CBRC).

- We expect this pace of lending to slow; the jump in real estate borrowing is at odds with government policy while bond financing conditions are improving for local governments.

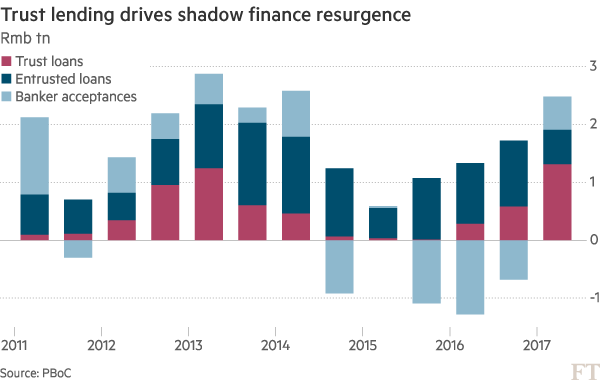

This year’s surge in trust loans confirms our earlier expectation that this channel of shadow finance would become popular again after bond financing costs increased and as the authorities cracked down on less regulated parts of the financial system (see chart). Trust lending may cool in the months ahead but for now we suspect regulators will allow this flow of credit as they concentrate on deleveraging in riskier areas.

Even if trust loan growth does slow, struggling firms will still want funding and the shadow finance system may again have to get creative in coming up with a channel for lending that bypasses regulatory scrutiny.

In trusts we trust

Net new lending by trusts — 68 licensed non-bank lenders subject to less stringent regulations than mainstream banks — hit Rmb1.31tn ($195bn) in the first half versus Rmb902.5bn over the whole of 2015 and 2016 (see chart).

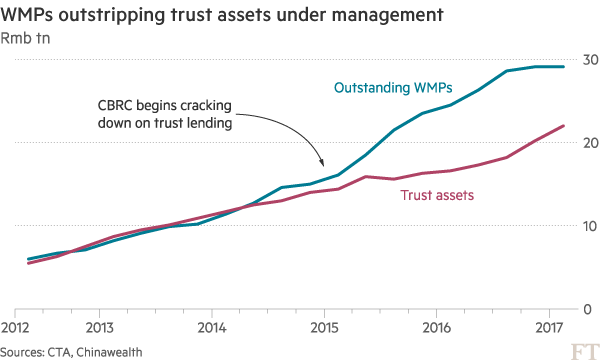

The growth of trust assets and outstanding wealth management products (WMPs) decoupled after a crackdown on the former in 2014, but the gap is narrowing again as trust assets increase once more and as the growth of outstanding WMPs slows on the back of government deleveraging (see chart). Although we believe asset growth has continued into the third quarter, we do not think this pace can continue.

The surge in trust lending this year has been the result of increased demand from:

Property developers

Since 2016, they have been restricted from the bond and stock markets and from obtaining bank loans as part

of a clampdown on housing market speculation. They sold just Rmb36.4bn in bonds in the first half of this

year, down from Rmb500bn during the same period last year. Funds raised through private stock placements

dropped 80.5 per cent in that time.

In this constrained environment, developers have turned again to trust companies for credit. Newly issued property-related trusts hit a record high of Rmb233.5bn in the fourth quarter, while trusts outstanding were up 21.7 per cent year-on-year in the first quarter at Rmb1.58tn. We believe trust exposure to the real estate market is considerably more than these data suggest.

Companies in overcapacity sectors

The end of the bond market rally closed off a source of cheap financing for companies in overcapacity industries,

such as coal and steel. Net bond financing by these firms was negative last year, in part down to the default

of state-owned China Shanshui Cement. Since the start of 2018, such companies have sold fewer bonds and at

shorter maturities, while trust loans have stepped into the breach (see chart). Industrial and commercial

trust assets grew 34 per cent year-on-year to Rmb4.7tn as of the end of March, accounting for 25.3 per cent

of total trust assets, and growth probably continued into the second quarter.

Local governments

Local government financing vehicles (LGFVs) used to be big business for trust companies, which were a large

source of loans for infrastructure projects. Tighter regulation and the opening of sanctioned channels —

such as direct bond sales and public-private partnerships — reduced this reliance.

But infrastructure trust financing growth jumped at the start of 2018 as local government bond issuance contracted on the back of the bond market sell-off (see chart).

This pace will not continue

We expect this scale of lending to slow through the remainder of 2018 and into next year. The increase in property-related trust lending looks increasingly out of kilter with the prevailing government line on controlling financial risks associated with the housing market.

We also expect reduced demand for trust lending from local governments as bond financing channels clear; local governments issued bonds worth Rmb845.3bn in July, a significant amount that bodes well for the pipeline through the remainder of the year. Finally, to the extent that the surge in trust lending reflects a shift in the shadow finance system away from less regulated credit sources, this is a process which may run its course as riskier shadow finance assets mature and are not renewed.

This is not to suggest an outright drop in credit activity in China. Companies such as those in overcapacity sectors are struggling to roll over outstanding obligations and the government has failed to clearly articulate how their reliance on debt is to be managed. Shadow finance channels will continue to play a central role in delivering loans to riskier borrowers.

Where’s the deleveraging?

The authorities consider the shadow finance system as an important source of credit for the economy but are clearly worried about its less regulated, more shadowy areas. Despite its intolerance for off-balance-sheet lending, we believe the government does not want to move too abruptly and risk destabilising the financial system — as happened in mid-2013 when the People’s Bank of China tried to put the interbank market on a crash diet.

This surge in trust lending may therefore reflect a government-sanctioned transfer of loans from the riskier parts of the shadow finance system back to a trust sector that is comparatively transparent.

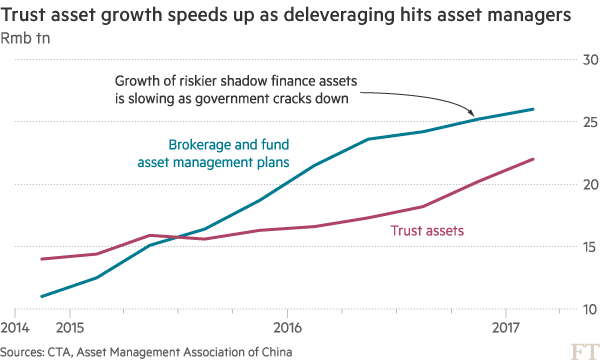

Even as trust lending is increasing, deleveraging is apparent in the fall in outstanding interbank WMPs and the slowing growth of more complex structures, such as directional asset management plans (DAMPs) and trust beneficiary rights (TBRs), which are channelled through brokerages and fund management companies and are loans by another name (see chart).

Reliance on trusts would make sense from a regulatory standpoint. The CBRC has oversight for trusts and banks, and has arguably shown greater competence in recent years than its counterparts in the insurance and securities industries.

This shift of business around the shadow finance system would also explain why the pricing of trust products does not reflect prevailing market conditions. Just two years ago, such products were offering close to 9 per cent, versus less than 7 per cent now. Yields have risen slightly amid the broader market sell-off, but nowhere near the extent of corporate bonds or returns on WMPs (see chart).

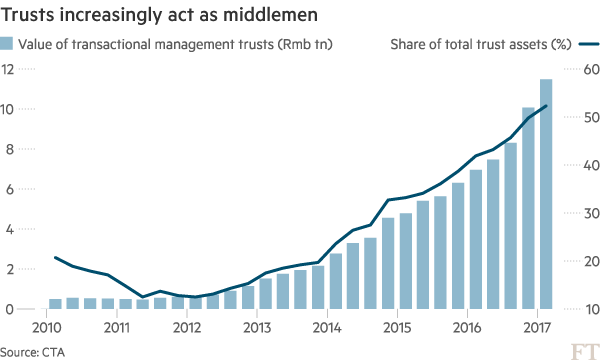

Banks may be pushing for below-market returns on instruction from regulators to ensure the successful transfer of shadow finance money from other channels back to the trust sector. Much of the increase in trust lending this year has been from those trusts that act as middlemen for banks in exchange for a fee, the so-called “channel business”. These trusts account for 52.3 per cent of trust assets under management and the pricing of their products would be enough to influence the returns on other trust product categories (see chart).

These moves could mark an improvement in governance even if they fail to answer the question of how companies are to break their reliance on debt to stay afloat.

As the provision of private health insurance grows from a low base across the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Asean) one trend stands out: the dominance of foreign providers.

The three biggest foreign players — Hong Kong-based AIA, Sun Life of Canada and the UK’s Prudential — appear to have benefited from a decades-long presence in key Asean markets, coming top in our latest quarterly survey of preferred health insurance providers.

In Thailand AIA enjoys a significant advantage, using its almost 80-year life insurance presence to cross-sell health insurance products. Similarly, Prudential’s presence in Malaysia since 1924 partly helps to explain its second-ranked position in Asean’s third-largest economy.

Under-developed public healthcare systems and increasing healthcare demand across the region are key drivers of the business. This means there is likely still to be plenty of room for domestic players to grow.

In Vietnam, the dominance of state-controlled Bao Viet — which a third of respondents cited as their preferred health insurance provider — is likely to continue given its extensive branch network. The insurer last year launched the country’s first cancer insurance policy.

— Ben Heubl, Data Visualisation Analyst

The advertisement on the London Underground this summer told the story. Next to a map of the Metropolitan Line and a sales pitch for a herbal remedy for stress was a solicitation for an investment fund giving punters a chance to bet on bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies. “Crypto needn’t be cryptic,” it informed commuters.

The mass-market campaign made sense because bitcoin — a digital currency created by geeks that very few people understand — has become the investment nearly everyone is talking about. Worth little more than $300 at the start of 2015, the price of one bitcoin rocketed past the $10,000 mark and then $11,000 this week before settling around $10,550 on Friday in roller-coaster trading that tested the capacity of dealing platforms in the nascent asset class and stoked fears of a bubble.

The dramatic price action — at a time of low volatility in stocks and bonds — has proved impossible for the financial world to ignore. Nasdaq, the US exchanges operator, said on Wednesday it planned to launch bitcoin futures contracts next year, which would make it easier for investors to profit from losses as well as gains in the cryptocurrency. The move followed similar decisions by rivals Chicago Mercantile Exchange and Chicago Board Options Exchange.

Big banks that serve as intermediaries in such markets — enabling them to make money from price swings in either direction — have considered joining the futures trade, despite doubts about the underlying product both as a store of value or a means of payment. JPMorgan Chase — headed by Jamie Dimon, who has called bitcoin a “fraud” — is thinking about helping clients trade bitcoin futures, according to a person familiar with the matter. Goldman Sachs said it is exploring a similar market-making role, in response to client demand.

“It’s not for me, but there’s a lot of things that weren’t for me in the past that worked out very well,” Lloyd Blankfein, Goldman’s chief executive, said this week. “Based on everything I know, I’m not guessing that it will work out. But I can’t say . . . it’s a fraud, it can’t [work out], because it might.”

The prominence of bitcoin marks an unlikely outcome for a product born in 2009 as an open-source computing project inspired by the mysterious Satoshi Nakamoto. That was the name used by the person or people who wrote the paper describing the digital currency. No one has been able to establish whether there really is a Mr Nakamoto.

Bitcoin itself is a string of computer code. New bitcoins can be created — up to an agreed limit — by computers that gain the right to do so by solving complex puzzles. Transactions are recorded in a database called a blockchain.

The identity of those behind the transactions is hidden. Cryptographic techniques are used to prevent fraud — which is why bitcoin and its imitators such as ethereum are called cryptocurrencies. Neither governments nor banks play a role.

The result has been an investment mania made for the times. Futurists, libertarians and computer nerds turned to blockchain as a way to bring people together (there is even one recent project, called Thrive, using “wisdom of crowds” technology to “eradicate fake news”). Their cryptocurrencies found support among investors who have lost faith in people and their institutions — most notably, governments and banks.

Robert Shiller, the Yale economist who wrote Irrational Exuberance, sees the demand for bitcoin arising from the same sort of anxieties about modern life that helped elect Donald Trump as US president.

“Somehow bitcoin fits into that and it gives a sense of empowerment: I understand what’s happening! I can speculate and I can be rich from understanding this! That kind of is a solution to the fundamental angst,” he told Quartz.

The secrecy afforded by bitcoin and its cryptocurrency imitators provides a refuge for actors in the darker corners of the global economy.

“Bitcoin just shows you how much demand for money laundering there is in the world,” says Larry Fink, chief executive of BlackRock, the world’s largest money manager.

Joseph Stiglitz, the Nobel Prize-winning US economist, has said it ought to be outlawed. “Bitcoin is successful only because of its potential for circumvention, lack of oversight,” he said this week. “It doesn’t serve any socially useful function.”

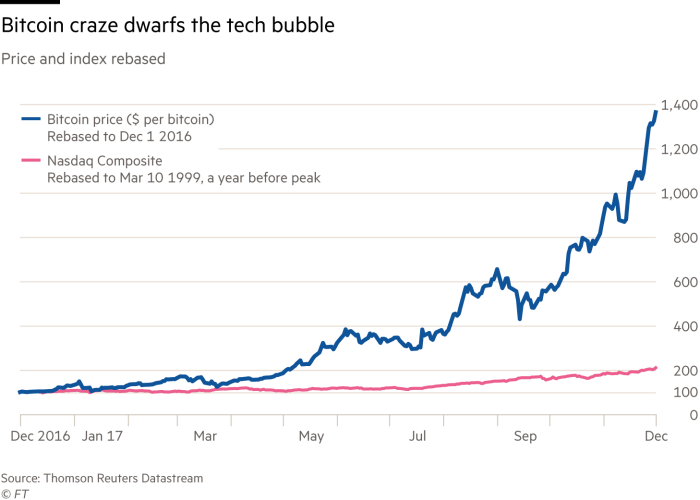

The surge in Bitcoin’s value is arguably unprecedented. In the 12 months to November 30, the bitcoin price rose 1,773 per cent, bringing its value to nearly $170bn, around the market capitalisation of General Electric. By comparison, the Nasdaq Composite barely doubled during the final year of the dotcom boom. Other stock market bubbles, such as in the US in 1929, Japan in 1989 or China in 2007, were of much the same magnitude as the tech sector’s.

Bitcoin satisfies most of the classic conditions for an investment mania. In his seminal 1978 work, Manias, Panics and Crashes, Charles Kindleberger said such episodes could start with “the widespread adoption of an invention with pervasive effects” that lie in the future and are hard to value.

Loose monetary policy — of the kind that followed the 2008 financial crisis — can provide additional fuel for investment crazes. As prices increase, peer pressure takes over. The number of hedge funds that invest in cryptocurrencies rose from 55 at the end of August to 169 by this week, according to research firm Autonomous NEXT.

“There are massive similarities between the dotcom bubble and bitcoin,” says Clare Nicholls, senior partner at Invenio Corporate Finance. “The dotcom bubble was driven largely by ‘fear of missing out’. Many people acted without really understanding what they were doing or the real truth behind it. As a result, prices skyrocketed and now, over a decade later, we are looking at the same volatile situation.”

The action was more than some participants could handle. Coinbase, one of the largest exchanges, said on Wednesday that its traffic was at an “all-time high”, resulting in “slower performance” for users. Gemini, another large exchange, suffered intermittent outages on Wednesday and Thursday as it dealt with an “enormous influx of traffic”.

“Some exchanges are dealing with tens of thousands of accounts being opened,” says Javier Paz, analyst at consultancy Aite Group in New York. “That’s when you are getting a bottleneck and operational issues. Their middle and back offices are clogged up.”

London’s IG Group, the UK’s largest online trading platform by market share, suspended trading of some bitcoin derivatives contracts on Monday. It offers punters a chance to play in the market using a “contract for difference”, in which participants exchange the difference between the price at the time of the trade and at settlement. Mr Paz says derivatives dealers were “sensing the fragility of liquidity” in the market.

The rapid turnover introduced a new risk factor — newcomers with less of an ideological commitment to bitcoin. As the $10,000 threshold neared, many long-term holders sold, says Gavin Brown, senior lecturer in financial economics at Manchester Metropolitan University and director of cryptocurrency hedge fund Blockchain Capital.

“For years, on the [online discussion] forums, $10,000 was the psychological barrier, it was the dream number,” Mr Brown says. “People who have been in the market for four years are now cashing out . . . with life-changing returns.”

As they did, regulators expressed fresh concerns. Randal Quarles, the Federal Reserve official who oversees banks, warned on Thursday that digital currencies are a “niche product” that have yet to prove themselves in a time of crisis. His words came only weeks after Chinese officials moved to shut down public bitcoin exchanges.

“Without the backing of a central bank asset and institutional support, it is not clear how a private digital currency at the centre of a large-scale payment system would behave, or whether the payment system would be able to function, in times of stress,” he said.

Ultimately, it is hard to say what exactly investors are buying. Bitcoin is as odd a duck as its supposed creator, Mr Nakamoto. Unlike stocks or bonds, bitcoin has no income stream. Unlike industrial or agricultural commodities, it has no practical use that can help to calculate an intrinsic value. While described as a currency, it may make most sense to compare it to precious metals. Gold’s price rose 314 per cent in the final year before its 1970s bull market peaked in 1980, while silver rallied by 720 per cent.

“Bitcoin is an electronic commodity used for payment that has become a vehicle for speculation,” says William Goetzmann, a Yale economist. “It does not have future dividends. Its value is set by expectations of future demand and/or expectations of future resale value. There is no way to value it fundamentally.”

None of this means the boom will end any time soon. Mike Novogratz, the hedge fund manager who last week forecast a value of $10,000 for bitcoin by the end of this year, says it could reach $40,000 by the end of 2018. But, by the same token, this week’s market gyrations suggest that punters who have just climbed aboard the bitcoin train can expect, at the minimum, a bumpy ride.

Sohan Lal, a 52-year-old sharecropper in India’s heartland state of Madhya Pradesh, has long faced the typical problems of the country’s 120m farmers, from the vagaries of the weather to fluctuating commodity prices. But these days, Mr Lal, who cultivates wheat and soyabean on 3 acres in Pipaliya Mira village, is confronting a new menace that is causing havoc across India’s rural economy: stray cows that intrude on his fields and eat his crops.

In 2004 the state government, controlled by the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata party whose orthodox Hindu supporters revere cows as near deities, passed a new law banning all cattle slaughter. The legislation — which also prohibits taking aged cows out of the state for slaughter — was amended in 2012 to extend prison sentences and to shift the burden of proof on to suspects, who are now presumed guilty unless they can prove their innocence.

With patrols of aggressive youth acting as enforcers, the ban upended the economics of keeping dairy cattle, destroying a thriving market for aged cows or male calves, which were previously valued for meat and hides. Today, unwanted bovines are just dumped, under cover of darkness, along highways or in other villages, resulting in a sharp surge in feral cattle.

“People can’t afford to feed them so they just abandon them at night,” Mr Lal says. “Crops are being destroyed by both bulls and abandoned cows. If we are awake, we chase them away from the fields. Otherwise, they just destroy everything.”

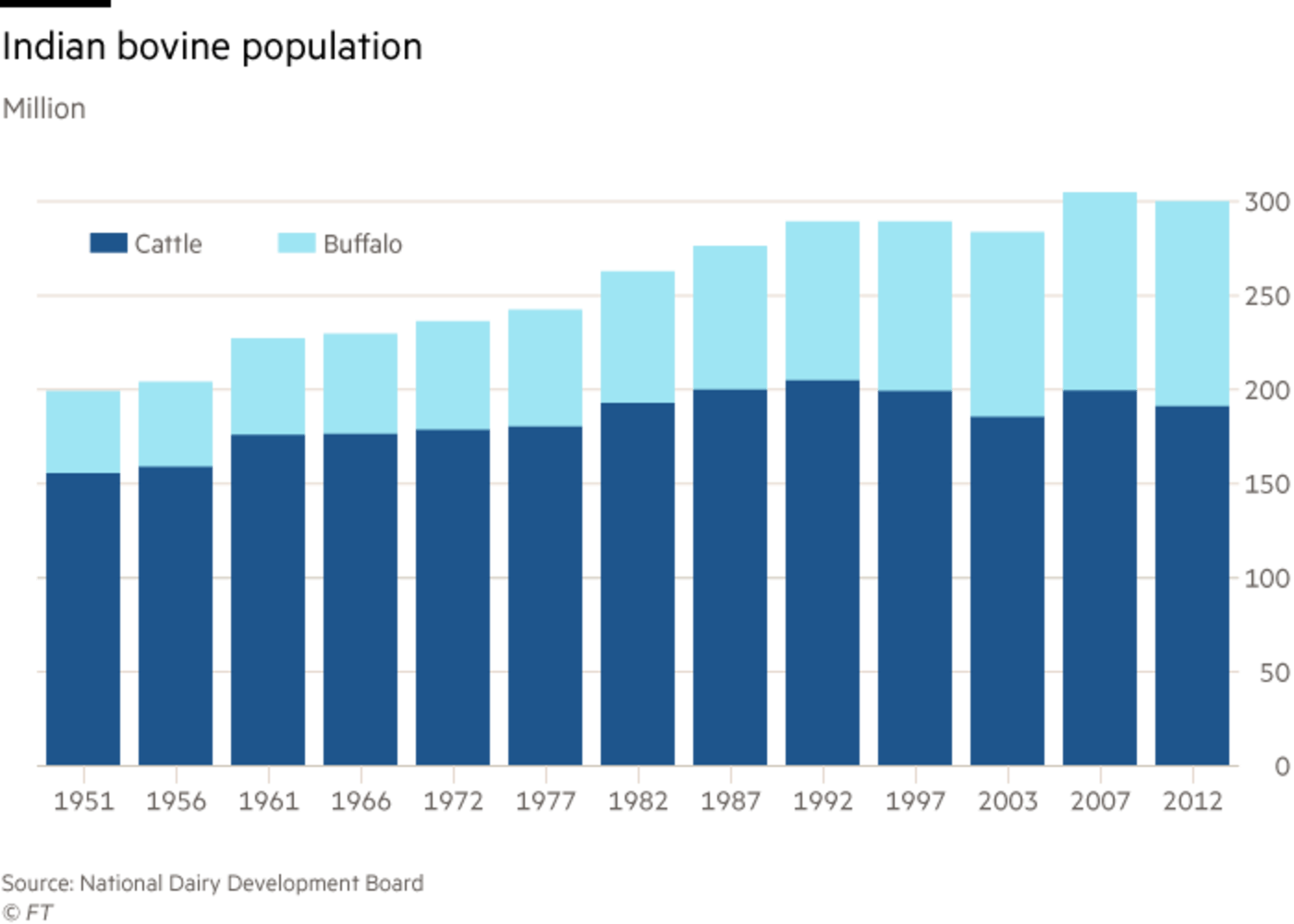

Already the world’s largest milk producer, India is struggling to keep pace with the demands of a more affluent population for nutritious food. But stray cattle are a growing problem as an ascendant BJP, led by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, uses its expanding power to strengthen cow protection laws and restrict the bovine trade, fulfilling its longstanding pledge to defend the gau mata, or “cow mother”.

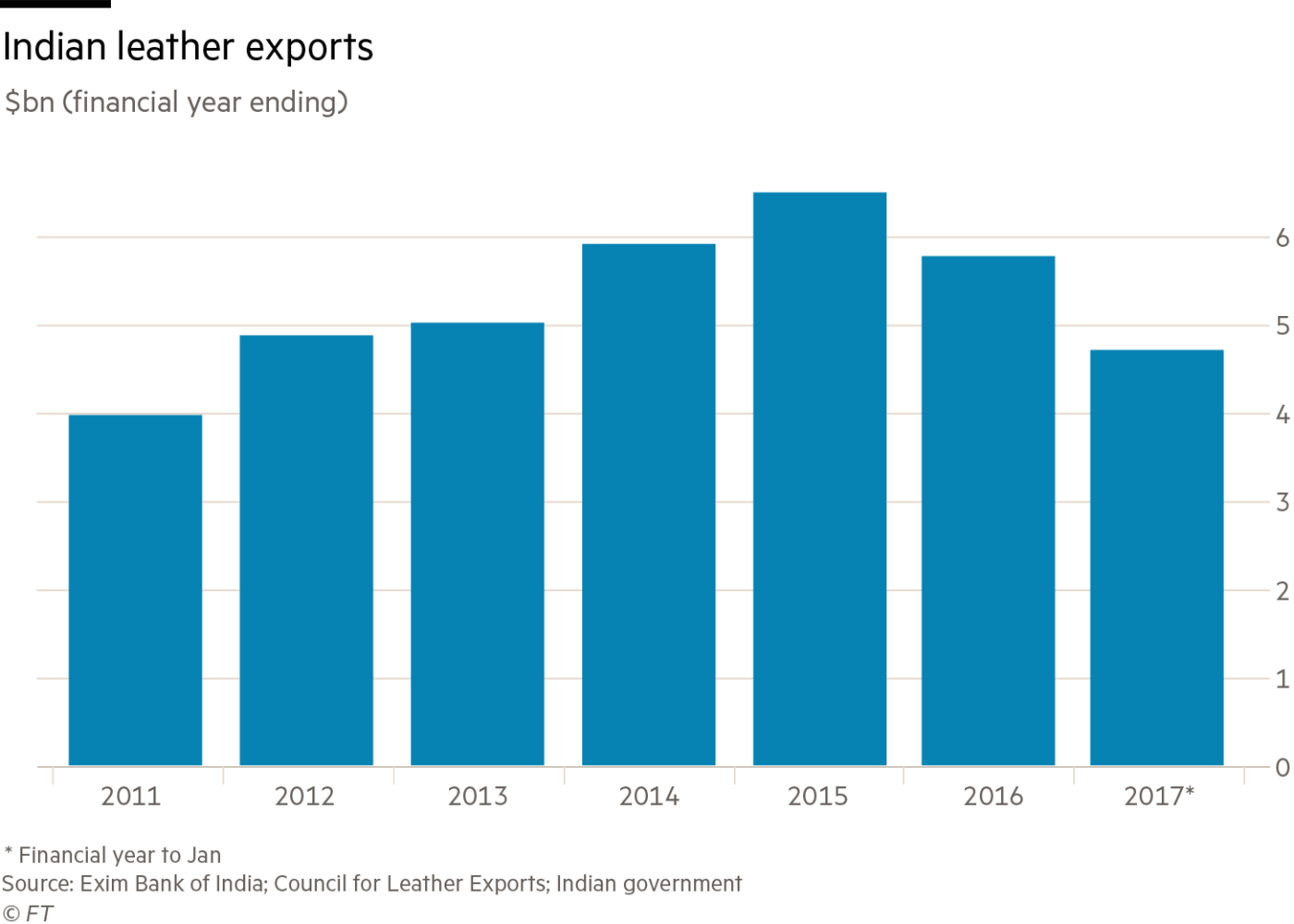

The disruption of complex supply chains that had linked Indian dairy farmers to leather and meat exports worth about $11bn in 2016, highlighted a fundamental contradiction at the heart of Mr Modi’s administration.

In 2014, the prime minister was swept to power on a promise to accelerate economic growth and create new opportunities for the 12m young Indians entering the job market each year. But his promise of economic revival was laced with an undercurrent of Hindu nationalism, which seeks to privilege the religious sensibilities of India’s Hindu majority in public policy.

In its pursuit of stronger cow protection laws — at the expense of industries that together employ at least 5.5m people — Mr Modi’s BJP has signalled that the Hindu nationalist cultural agenda trumps economic interests, including the urgent need for job creation.

“Cow protection has been a core issue that has defined the Hindu nationalist movement since its inception,” says Gilles Verniers, a political science professor at New Delhi’s Ashoka University. “It’s not something that can be ditched easily for the sake of an economic argument. They are ready to bear the cost. And politically, they think it’s more rewarding. The gains outweigh the cost.”

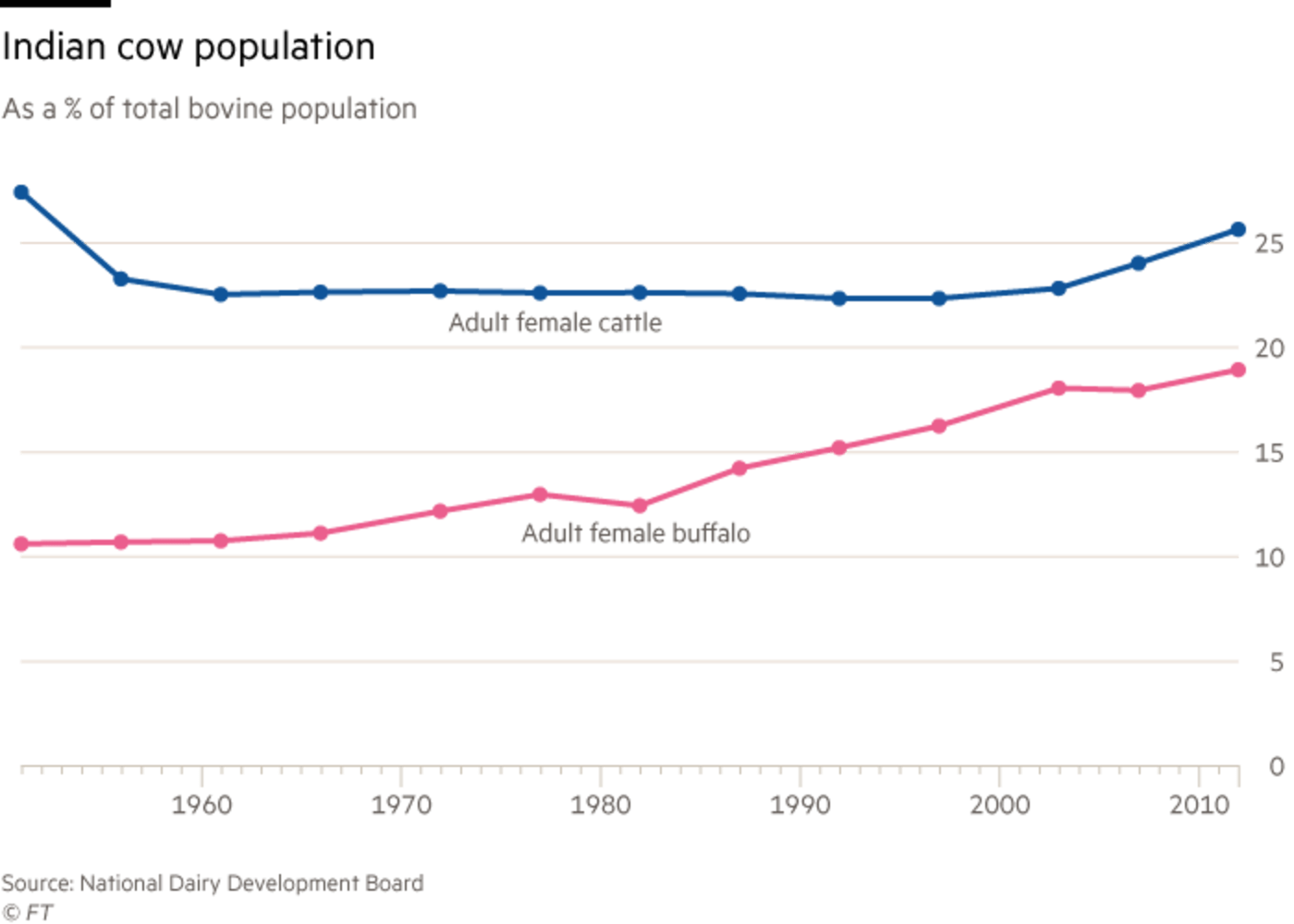

Economists say the tough cow protection policies are a blow to rural households, half of which keep bovines, both as a source of milk for their own consumption and to generate income. Experts warn of stagnating milk production, and sharp increases in price.

“It’s bizarre that the macro implications of this haven’t been considered,” says Ravi Srivastava, an economics professor at Jawaharlal Nehru University’s Centre for the Study of Regional Development in Delhi. “You are turning an asset into a liability.”

“If farmers are not able to sell their redundant cattle, the cost per unit of milk would have to go up horrendously for the rest of the dairy economy to be viable,” he adds. “More and more farmers are very disinclined to keep cattle.”

The country’s cow protection movement began in north India in the late 19th century, as upper-caste Hindus sought to resist western influence and spur nationalist sentiment. The cow, the heart of rural economies, was elevated to the symbolic “mother of the Hindu nation” — an idea propagated in posters, pamphlets and public meetings.

Cow protection societies sprang up across north India and in big cities, pushing — unsuccessfully — to criminalise cow slaughter. “The cow was always an essential companion of everyday life in rural India,” says Mr Verniers. “It essentially became a symbol of Hindu national identity, which was not so much centred around religion, but around cultural symbols that are evocative of the motherland.”

The elevation of the cow to a sacred national symbol also fuelled tensions, dividing Hindus from Muslims, who had no taboo on eating beef and sometimes sacrificed the animals for their own festivals. Communal riots over cow slaughter erupted in 1893, and recurred in the following decades.

After India’s independence in 1947, conservative Hindu leaders pushed for a national cow slaughter ban in the constitution. That demand was rejected, though a “directive principle” urged individual states to prohibit slaughter of cows or draught animals that could pull ploughs or carts.

Since the 1950s, many states have banned the killing of productive cattle. But the killing of aged animals was often allowed, creating a robust rural market for animals that could no longer give milk or pull ploughs, many of which were sold to traders in neighbouring Bangladesh.

As India’s milk production has risen in the past two decades, so too have meat and leather exports, driven by the natural rotation of milk-producing animals and growing mechanisation of agriculture, which has seen a sharp rise in the use of tractors and reduced demand for bulls.

But on the campaign trail in 2014, Mr Modi publicly decried India’s rising meat exports, which he described repeatedly in emotive terms as a “pink revolution” — a reference to flesh and blood — destroying the local cattle population. “People who slaughter cows, who slaughter animals, are destroying our rivers of milk,” he told a large rally.

Since then, the BJP has pushed to quash the cattle trade. BJP-ruled states widened their cow protection laws to stop the slaughter of even aged, unproductive animals, ban the interstate transport of cattle and impose tougher penalties on the guilty — up to life imprisonment for killing a cow in Mr Modi’s home state of Gujarat.

This summer, New Delhi issued a national order making it a criminal offence to buy or sell any bovines — including buffaloes — for slaughter in any cattle markets, though the rules were set aside by the Supreme Court in response to legal challenges.

North India has also seen the rise of violent “cow defenders”, responsible for a series of lethal attacks on Muslim farmers and livestock traders, killings that have created a climate of fear and severely depressed once-active markets for cattle, both young and old. “The supply chain has been completely disrupted because there are no traders coming into the villages,” says Mr Srivastava. “They are very, very afraid.”

The most immediate hit has been felt by India’s leather industry, especially established leather hubs in BJP-ruled Uttar Pradesh in northern India, where the supply of hides has become highly erratic, due to the vigilantism.

“People are afraid to move the hides because the vigilantes can stop the leather movement on the ground,” says M Rafeeque Ahmed, former chairman of the Council for Leather Exports.

The domestic hide supply, he says, is “on and off. It’s OK for a while, until something happens, then it gets disturbed for a few weeks. Then it gets back to normal. But factories cannot function like that. We should have assured supply all the time.”

Given this, many Indian leather goods producers — including those making shoes and other products — have started importing hides from abroad. “People that have been using Indian leather want to be sure that their factories run, so they are importing more,” Mr Ahmed says.

But the cow protection movement has also cast a long shadow over milk production.

“Dairying is totally tied in with the freedom of the farmer to sell your animal and replace your stock,” says Sagari Ramdas, a veterinarian affiliated with the Food Sovereignty Alliance. “If the farmer is no longer going to have that freedom, it could have severe implications for the production of milk.”

The prosperous agricultural state of Punjab — where Nestlé has its largest Indian milk packing and processing plant — is at the forefront of India’s efforts to increase its milk output.

With supply still lagging behind demand, rising milk prices have been big drivers of food price inflation over the past decade.

“We do need more milk,” says Amarjit Singh Nanda, vice-chancellor of Ludhiana’s Guru Angad Dev Veterinary and Animal Sciences University. “Our animals are not having the best productivity compared to the developed world.”

Punjab’s enterprising farmers have largely turned their back on India’s indigenous cattle, instead raising foreign cross-breeds like the Holstein-Friesian, regarded as the world’s highest-producing dairy cows. As a result, Punjab produces 8 per cent of India’s milk, from just 2 per cent of its dairy animals.

Punjabi farmers have also been breeding the high-yielding Holstein-Friesian cows — which are worth nearly Rs100,000 ($1,500) each — and selling them to farmers across north India, helping to raise the nation’s milk output.

But restrictions on cattle sales and cow protection vigilantism in BJP-ruled states have led to a collapse in demand for the expensive animals, with farmers reluctant to make such purchases any longer, due to uncertainty over whether they can recoup their costs.

Vigilantes in Punjab’s neighbouring states often demand that transporters pay Rs15,000 ($230) or Rs20,000 per cow before they will permit the trucks to proceed to their destination.

“The cow I was selling for Rs90,000, now I’m selling for Rs50,000,” says Avtar Singh, a cattle breeder who says his only sales are now to farmers in Punjab. “People are humiliating the traders, saying these animals are their mothers.”

Mr Nanda warns that “India will face a milk crisis” if such trends continue. “The growth in dairying will stop.”

Ajay Vir Jakhar, chairman of Punjab Farmers Commission, agrees that the disruption to the livestock trade will have significant repercussions for the production of milk. “People will stop keeping dairy animals because it’s not viable any more,” he says.

“India will become a net importer of milk in 10 years’ time,” he adds. “We will be completely dependent on buying milk from abroad.”

Cost of care: states step in to stem the rise of stray cows

As stray cow numbers grow with the tightening of controls on their slaughter, the government led by the Bharatiya Janata party is supporting the establishment of “gaushalas” or cow shelters, which are intended to provide shelter to elderly, unwanted cattle.

In Madhya Pradesh, the state government has provided land for setting up village gaushalas, as well as a Rs500 annual subsidy for each resident bovine. But Lalit Tyagi, who helps his grandfather run a community gaushala in Titora village, says the state funds are insufficient as the cost of feeding a cow for one year is nearly Rs6,000.