Welcome to the Best of the FT:

Below you’ll find a curation of the top read articles of our award-winning journalism from 2017 amongst your peers in asset & wealth management. This selection showcases a range of topical news articles, exclusives, popular features as well as premium commentary and analysis.

Your “springboard” guide to current market concerns, presented in a logical and concise manner, with direct links to more details.

- Volatility winners (new)

- S&P 500 nears key level

- Cboe’s troubles

- EMs turn to local debt

- Expect more dividend cuts in UK

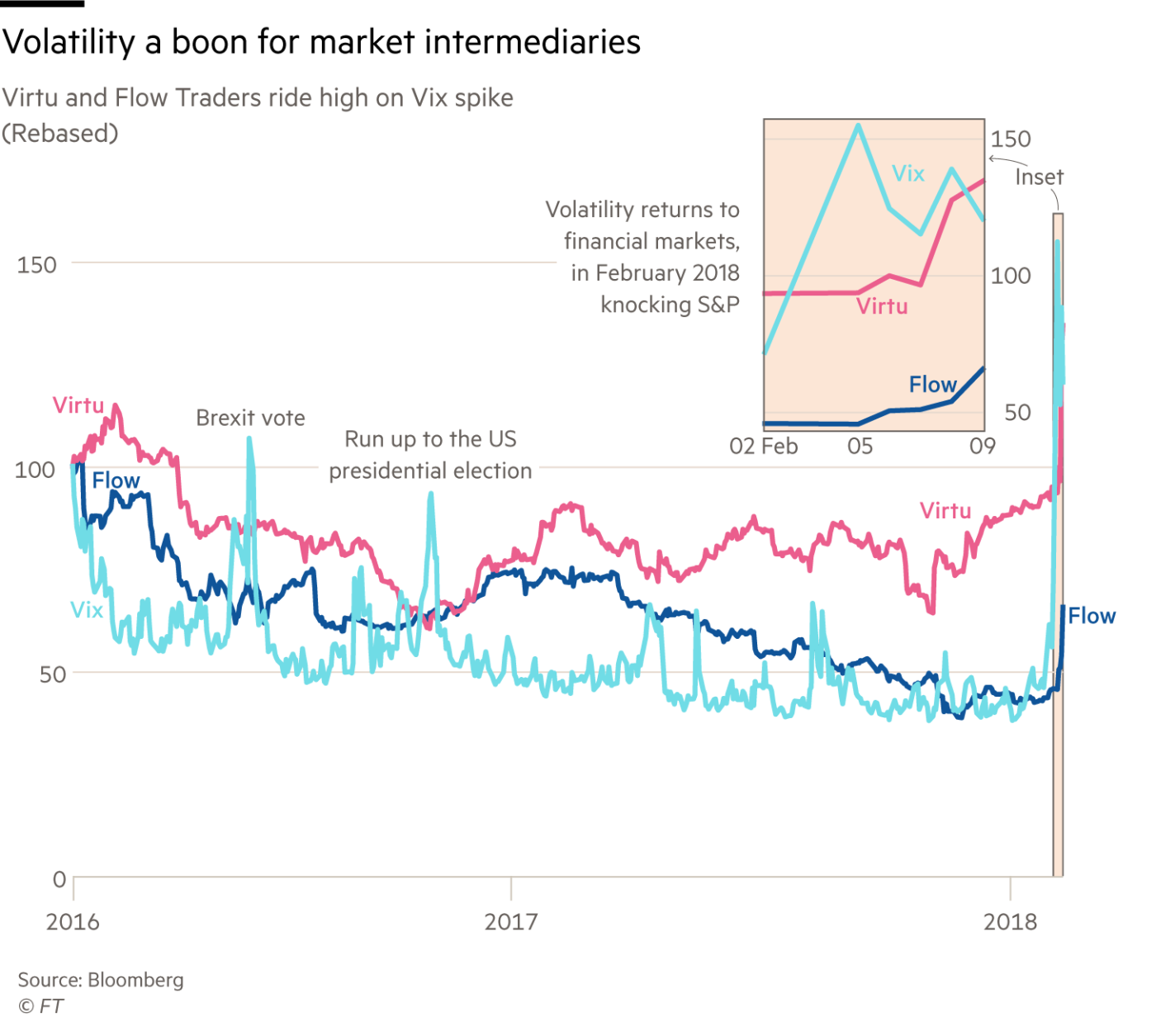

The sudden upsurge in volatility has been a boon for the market’s intermediaries. For high-frequency traders the last 10 days have been an oasis in the desert.

Most of these companies, such as DRW Holdings, Citadel Securities and Two Sigma, account for the majority of volume on global equities, futures and foreign exchange markets.

They use their own money to trade and quote bid and offer prices, and earn profits by using computer algorithms to exploit differences in the spread between bid and ask prices, ending the trading day with minimal open positions.

After a boom during the financial crisis years, the industry has been hard hit in recent years by low volatility, rising technology costs and a regulatory crackdown on behaviour and practices in electronic trading. Many of the smaller market competitors have been sold to rivals.

Most are small and private but two, the US’s Virtu Financial, and Flow Traders of the Netherlands, are listed on their home markets, with market capitalisations of $5bn and €1.4bn respectively. Shares in both have surged by more than a quarter in the last seven days on investors’ hopes that higher market volatility will lead to improved corporate profits.

“The environment where you have a lot of price changes during the day is the ideal environment for a market maker,” said Doug Cifu, chief executive of Virtu.

For him last week’s blow-up in products related to the performance of the Vix volatility index was not an issue. “We make markets in 2,000-ish exchange-traded products around the world and if a small handful of them are having issues, it really has no impact at all on our performance going forward.”

But investors should be wary; there have been notable spikes in volumes and volatility in the past and it has not translated into sustained earnings. Whether this is cyclical or temporary remains to be seen. Philip Stafford

The S&P 500 has entered official correction territory, having fallen more than 10 per cent from its peak of 2,872 late last month. Selling has been concentrated in US large-cap equity funds, tech and healthcare, says Bank of America Merrill Lynch in their weekly review of investor flows that includes Monday’s rout on Wall Street.

Some measure of support should beckon in the form of the 200-day moving average at 2,538. The market last tested the 200-day MA just before the US election presidential election in November 2016.

BofA thinks this level represents a good entry point in the coming weeks.

One element of caution is that when the 200-day breaks, the market can take a while to heal its wounds. At the start of 2016, the S&P broke down and didn’t climb back above this measure of momentum until mid-March. This reflects how the process of creating a market low takes time or, in other words, we need to see the S&P 500 bounce up and down and make a second test of a certain level (1,810 in January, and February of 2016 was the low point for that correction)

Another important point is that plenty has changed in the past two years, not the least a gain of more than 40 per cent in the S&P 500 from its mid-March 2016 nadir. Then, investors worried about a China-led global economic slowdown. Falling bond yields and still very accommodative central banks ultimately helped equities find their footing.

Now the worry is higher bond yields and inflationary concerns as the global economy boasts its best run of synchronised growth since the financial crisis.

Next week’s US inflation data looms as a critical piece of the puzzle facing investors and likely determines whether we get some relief or a bigger test of the downside.

As Lena Komileva at G+Economics notes: “The severity of market moves has exposed how unprepared and unhedged markets are to a return to a more normal rates and liquidity environment.”

She also highlights that the UK market’s sharp reaction to the Bank of England’s hawkish message this week illustrates “how acutely sensitive investor portfolios are to the end of the crisis-era policy stimulus”. Michael Mackenzie

Exchange-traded products that allow investors to wager on the tranquility of Cboe’s Vix index, a measure of stock market volatility, have helped drive Cboe’s profits in recent years. The exchange-traded notes relied on Vix futures, which can only be traded at Cboe.

But analysts fear the slide in value of two big notes and funds this week will have a bigger impact. Goldman Sachs estimated Vix futures contributed about 40 per cent of Cboe’s earnings growth between 2015 and 2017, excluding its 2016 deal for Bats Global Markets.

Kenneth Worthington, an analyst at JPMorgan, said the liquidation of the exchange-traded notes was “potentially the tip of the iceberg” as trading activity in Vix futures fell away in coming months. If the market moves from its preferred strategy of shorting volatility to one where hedging its risk was dominant, investors might look to other futures contracts, such as CME’s E-mini, he said. Philip Stafford

Should investors worry about debt in emerging markets? The past week’s global market sell-off, and the rise in US interest rates that lies behind it, suggest they should at least keep a very close eye.

Our chart shows the total debts of 21 EM countries compiled by the Institute of International Finance, an industry association and data gatherer. It includes debts owed by governments, households, companies and the financial sector, in local and foreign currencies.

One of the selling points of EMs during the rally in their stocks and bonds over the past two years has been the improvement in their macroeconomic fundamentals. Dangerous current account deficits have largely been dealt with, the narrative goes, and the debt overhangs of the past have been reduced, thanks partly to a transition from foreign currency debts, which leave borrowers exposed to foreign exchange movements beyond their control, into local currency debts, which governments can do more about (such as inflating them away in times of difficulty).

Indeed, there is much less EM debt today than there was in the crisis years of the 1980s and 1990s. But since the global financial crisis of 2008-09, EM debts have been on the rise again. In dollar terms, in the IIF’s 21 countries, they quintupled from $12tn in March 2005 to $60tn in September last year. In relation to gross domestic product, they rose from 146 per cent to 217 per cent.

Significantly, as the chart shows, the amount of debt owed in foreign currencies has also risen over the same period, both in absolute terms and as a share of GDP.

The picture is far from even across EMs. But in aggregate — which is how many investors view them — emerging markets are more indebted today than at any point since the 2008-09 crisis. As global financial conditions begin to tighten, that is something to watch. Jonathan Wheatley

Rising bond yields as central banks slowly retreat from the era of easy money has already been a challenge for dividend-paying companies. So far this year, Wall Street dividend payers are lagging behind the broad market. We are also seeing an interesting trend from the UK, where a number of companies have issued profit warnings and cut their payouts.

Andrew Lapthorne at Société Générale notes that their monthly dividend risk screen of high dividend yield stocks with poor quality balance sheets is dominated by the UK. Of the current 50 companies that comprise the list, 21 are listed in the UK.

In broader terms, what makes this all the more interesting is whether the UK is the proverbial canary in the coal mine. Loading up balance sheets with debt and keeping dividends flowing has not just been a UK story during the easy money era for many companies around the world.

Longview Economics, for example, estimates that some 12 per cent of US companies are “zombies” — defined as having earnings before interest and tax that do not cover their interest expense.

The big difference at the moment is that a weaker UK economy compared with the rest of the world is a catalyst for profit warnings from indebted companies that herald a dividend cut.

As global bond yields rise, Mr Lapthorne says we are seeing a substantial move against low-quality credit. Any tempering of global growth will weigh against companies with weak balance sheets that pay chunky dividends. Michael Mackenzie

It is not true that humanity cannot learn from history. It can and, in the case of the lessons of the dark period between 1914 and 1945, the west did. But it seems to have forgotten those lessons. We are living, once again, in an era of strident nationalism and xenophobia. The hopes of a brave new world of progress, harmony and democracy, raised by the market opening of the 1980s and the collapse of Soviet communism between 1989 and 1991, have turned into ashes.

What lies ahead for the US, creator and guarantor of the postwar liberal order, soon to be governed by a president who repudiates permanent alliances, embraces protectionism and admires despots? What lies ahead for a battered EU, contemplating the rise of “illiberal democracy” in the east, Brexit and the possibility of Marine Le Pen’s election to the French presidency?

What lies ahead now that Vladimir Putin’s irredentist Russia exerts increasing influence on the world and China has announced that Xi Jinping is not first among equals but a “core leader”?

The contemporary global economic and political system originated as a reaction against the disasters of the first half of the 20th century. The latter, in turn, were caused by the unprecedented, but highly uneven, economic progress of the 19th century.

The transformational forces unleashed by industrialisation stimulated class conflict, nationalism and imperialism. Between 1914 and 1918, industrialised warfare and the Bolshevik revolution ensued. The attempted restoration of the pre-first world war liberal order in the 1920s ended with the Great Depression, the triumph of Adolf Hitler and the Japanese militarism of the 1930s. This then created the conditions for the catastrophic slaughter of the second world war, to be followed by the communist revolution in China.

In the aftermath of the second world war, the world was divided between two camps: liberal democracy and communism. The US, the world’s dominant economic power, led the former and the Soviet Union the latter. With US encouragement, the empires controlled by enfeebled European states disintegrated, creating a host of new countries in what was called the “third world”.

Contemplating the ruins of European civilisation and the threat from communist totalitarianism, the US, the world’s most prosperous economy and militarily powerful country, used not only its wealth but also its example of democratic self-government, to create, inspire and underpin a transatlantic west. In so doing, its leaders consciously learnt from the disastrous political and economic mistakes their predecessors made after its entry into the first world war in 1917.

Domestically, the countries of this new west emerged from the second world war with a commitment to full employment and some form of welfare state. Internationally, a new set of institutions — the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (ancestor of today’s World Trade Organisation) and the Organisation for European Economic Co-operation (the instrument of the Marshall Plan, later renamed the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) — oversaw the reconstruction of Europe and promoted global economic development. Nato, the core of the western security system, was founded in 1949. The Treaty of Rome, which established the European Economic Community, forefather of the EU, was signed in 1957.

This creative activity came partly in response to immediate pressures, notably the postwar European economic misery and the threat from Stalin’s Soviet Union. But it also reflected a vision of a more co-operative world.

From euphoria to disappointment

Economically, the postwar era can be divided into two periods: the Keynesian period of European and Japanese economic catch-up and the subsequent period of market-oriented globalisation, which began with Deng Xiaoping’s reforms in China from 1978 and the elections in the UK and US of Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan in 1979 and 1980 respectively.

This latter period was characterised by completion of the Uruguay Round of trade negotiations in 1994, establishment of the WTO in 1995, China’s entry into the WTO in 2001 and the enlargement of the EU, to include former members of the Warsaw Pact, in 2004.

The first economic period ended in the great inflation of the 1970s. The second period ended with the western financial crisis of 2007-09. Between these two periods lay a time of economic turmoil and uncertainty, as is true again now. The main economic threat in the first period of transition was inflation. This time, it has been disinflation.

Geopolitically, the postwar era can also be divided into two periods: the cold war, which ended with the Soviet Union’s fall in 1991, and the post-cold war era. The US fought significant wars in both periods: the Korean (1950-53) and Vietnam (1963-1975) wars during the first, and the two Gulf wars (1990-91 and 2003) during the second. But no war was fought among economically advanced great powers, though that came very close during the Cuban missile crisis of 1962.

The first geopolitical period of the postwar era ended in disappointment for the Soviets and euphoria in the west. Today, it is the west that confronts geopolitical and economic disappointment.

The Middle East is in turmoil. Mass migration has become a threat to European stability. Mr Putin’s Russia is on the march. Mr Xi’s China is increasingly assertive. The west seems impotent.

These geopolitical shifts are, in part, the result of desirable changes, notably the spread of rapid economic development beyond the west, particularly to the Asian giants, China and India. Some are also the result of choices made elsewhere, not least Russia’s decision to reject liberal democracy in favour of nationalism and autocracy as the core of its post-communist identity and China’s to combine a market economy with communist control.

Rising anger

Yet the west also made big mistakes, notably the decision in the aftermath of 9/11 to overthrow Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein and spread democracy in the Middle East at gunpoint. In both the US and UK, the Iraq war is now seen as having illegitimate origins, incompetent management and disastrous outcomes.

Western economies have also been affected, to varying degrees, by slowing growth, rising inequality, high unemployment (especially in southern Europe), falling labour force participation and deindustrialisation. These shifts have had particularly adverse effects on relatively unskilled men. Anger over mass immigration has grown, particularly in parts of the population also adversely affected by other changes.

Some of these shifts were the result of economic changes that were either inevitable or the downside of desirable developments. The threat to unskilled workers posed by technology could not be plausibly halted, nor could the rising competitiveness of emerging economies. Yet, in economic policy, too, big mistakes were made, notably the failure to ensure the gains from economic growth were more widely shared. The financial crisis of 2007-09 and subsequent eurozone crisis were, however, the decisive events.

These had devastating economic effects: a sudden jump in unemployment followed by relatively weak recoveries. The economies of the advanced countries are roughly a sixth smaller today than they would have been if pre-crisis trends had continued.

The response to the crisis also undermined belief in the system’s fairness. While ordinary people lost their jobs or their houses, the government bailed out the financial system. In the US, where the free market is a secular faith, this looked particularly immoral.

Finally, these crises destroyed confidence in the competence and probity of financial, economic and policymaking elites, notably over the management of the financial system and the wisdom of creating the euro.

All this together destroyed the bargain on which complex democracies rest, which held that elites could earn vast sums of money or enjoy great influence and power as long as they delivered the goods. Instead, a long period of poor income growth for most of the population, especially in the US, culminated, to almost everyone’s surprise, in the biggest financial and economic crisis since the 1930s. Now, the shock has given way to fear and rage.

The succession of geopolitical and economic blunders has also undermined western states’ reputation for competence, while raising that of Russia and, still more, China. It has also, with the election of Donald Trump, torn a hole in the threadbare claims of US moral leadership.

We are, in short, at the end of both an economic period — that of western-led globalisation — and a geopolitical one — the post-cold war “unipolar moment” of a US-led global order.

The question is whether what follows will be an unravelling of the post-second world war era into deglobalisation and conflict, as happened in the first half of the 20th century, or a new period in which non-western powers, especially China and India, play a bigger role in sustaining a co-operative global order.

Free trade and prosperity

A big part of the answer will be provided by western countries. Even now, after a generation of relative economic decline, the US, the EU and Japan produce just over half of world output measured at market prices and 36 per cent of it measured at purchasing power parity.

They also remain homes to the world’s most important and innovative companies, dominant financial markets, leading institutions of higher education and most influential cultures. The US should also remain the world’s most powerful country, particularly militarily, for decades. But its ability to influence the world is greatly enhanced by its network of alliances, the product of the creative US statecraft during the early postwar era. Yet alliances also need to be maintained.

The essential ingredient in western success must, however, be domestic. Slow growth and ageing populations have put pressure on public spending. With weak growth, particularly of productivity, and structural upheaval in labour markets, politics has taken on zero-sum characteristics: instead of being able to promise more for everybody, it becomes more about taking from some to give to others. The winners in this struggle have been those who are already highly successful. That makes those in the middle and bottom of the income distribution more anxious and so more susceptible to racist and xenophobic demagoguery.

In assessing responses, two factors must be remembered.

First, the post-second world war era of US hegemony has been a huge overall success. Global average real incomes per head rose by 460 per cent between 1950 and 2015. The proportion of the world’s population in extreme poverty has fallen from 72 per cent in 1950 to 10 per cent in 2015.

Globally, life expectancy at birth has risen from 48 years in 1950 to 71 in 2015. The proportion of the world’s people living in democracies has risen from 31 per cent in 1950 to 56 per cent in 2015.

Second, trade has been far from the leading cause of the long-term decline in the proportion of US jobs in manufacturing, though the rise in the trade deficit had a significant effect on employment in manufacturing after 2000. Technologically driven productivity growth has been far more powerful.

Similarly, trade has also not been the main cause of rising inequality: after all, high-income economies have all been buffeted by the big shifts in international competitiveness, but the consequences of those shifts for the distribution of income have varied hugely.

US and western leaders have to find better ways to satisfy their people’s demands. It looks, however, as though the UK still lacks a clear idea of how it is going to function after Brexit, the eurozone remains fragile, and some of the people Mr Trump plans to appoint, as well as Republicans in Congress, seem determined to slash the frayed cords of the US social safety net.

A divided, inward-looking and mismanaged west is likely to become highly destabilising. China might then find greatness thrust upon it. Whether it will be able to rise to a new global role, given its huge domestic challenges, is an open question. It seems quite unlikely.

By succumbing to the lure of false solutions, born of disillusion and rage, the west might even destroy the intellectual and institutional pillars on which the postwar global economic and political order has rested. It is easy to understand those emotions, while rejecting such simplistic responses. The west will not heal itself by ignoring the lessons of its history. But it could well create havoc in the attempt.

For the most ardent supporters of Brexit, the election of Donald Trump was a mixture of vindication and salvation. The president of the US, no less, thinks it is a great idea for Britain to leave the EU. Even better, he seems to offer an exciting escape route. The UK can leap off the rotting raft of the EU and on to the gleaming battleship HMS Anglosphere.

It is an alluring vision. Unfortunately, it is precisely wrong. The election of Mr Trump has transformed Brexit from a risky decision into a straightforward disaster. For the past 40 years, Britain has had two central pillars to its foreign policy: membership of the EU and a “special relationship” with the US.

The decision to exit the EU leaves Britain much more dependent on the US, just at a time when America has elected an unstable president opposed to most of the central propositions on which UK foreign policy is based.

During the brief trip to Washington by Theresa May, the UK prime minister, this unpleasant truth was partly obscured by trivia and trade. Mr Trump’s decision to return the bust of Winston Churchill to the Oval Office was greeted with slavish delight by Brexiters. More substantively, the Trump administration made it clear that it is minded to do a trade deal with the UK just as soon as Britain’s EU divorce comes through.

But no sooner had Mrs May left Washington than Mr Trump caused uproar with his “Muslim ban”, affecting immigrants and refugees from seven countries. After equivocating briefly, the prime minister was forced to distance herself from her new best friend in the White House.

The refugee row underlined the extent to which Mrs May and Mr Trump have clashing visions of the world. Even when it comes to trade, the supposed basis for their new special relationship, the two leaders have very different views.

Mrs May says that she wants the UK to be the champion of global free trade. But Mr Trump is the most protectionist US president since the 1930s. This is a stark clash of visions that will be much harder to gloss over — if and when Mr Trump begins slapping tariffs on foreign goods and ignoring the World Trade Organisation.

In addition, any trade deal with the Trump administration is likely to be hard to swallow for Britain and would involve controversial concessions on the National Health Service and agriculture.

The British and American leaders also have profoundly different attitudes to international organisations. Mrs May is a firm believer in the importance of Nato and the United Nations. (Britain’s permanent membership of the UN Security Council is one of its few remaining totems of great power status). But Mr Trump has twice called Nato obsolete and is threatening to slash US funding of the UN.

The May and Trump administrations are also at odds on the crucial questions of the future of the EU and of Russia. Mr Trump is openly contemptuous of the EU and his aides have speculated that it might break up. This reflects the views of Nigel Farage and the UK Independence party — but not of the current British government.

Mrs May knows that her difficult negotiations with the EU will become all-but-impossible if member states believe that the UK is actively working to destroy their organisation in alliance with Mr Trump.

Her official position is that Britain wants to work with a strong EU. She probably even means it, given the economic and political dangers that would flow from its break-up.

Not the least of these dangers would be an increased threat from a resurgent Russia. The British government worked closely with the Obama administration to impose economic sanctions on the country after its annexation of Crimea. But Mr Trump is already flirting with lifting sanctions.

The reality is that the UK is now faced with a US president who is fundamentally at odds with the British view of the world. For all the forced smiles in the Oval Office last week, the May government certainly knows this. For political reasons, Boris Johnson, the British foreign minister, is having to talk up the prospects of a trade deal with Mr Trump.

Yet only a few months ago, Mr Johnson was saying that Mr Trump was “clearly out of his mind” and betrayed a “stupefying ignorance” of the world.

Were it not for Brexit — a cause that Mr Johnson enthusiastically championed — the UK government would be able to take an appropriately wary approach to Mr Trump. If Britain had voted to stay inside the EU, the obvious response to the arrival of a pro-Russia protectionist in the Oval Office would be to draw closer to its European allies.

Britain could defend free-trade far more effectively with the EU’s bulk behind it — and could also start to explore the possibilities for more EU defence co-operation. As it is, Britain has been thrown into the arms of an American president that the UK’s foreign secretary has called a madman.

In the declining years of the British empire, some of its politicians flattered themselves that they could be “Greeks to their Romans” — providing wise and experienced counsel to the new American imperium.

But the Emperor Nero has now taken power in Washington — and the British are having to smile and clap as he sets fires and reaches for his fiddle.

Mifid II: how asset managers will pay for research

Data as of 10.30 on December 15 2017

Pass costs on to clients

Carmignac

Deka

Fidelity International

Absorb Costs

Allianz Global Investors

Amundi*

Artemis

Ashmore*****

Aviva Investors

Axa Investment Managers

Baillie Gifford

Barings

BlackRock

BlueBay Asset Management

BNP Paribas***

Brewin Dolphin

Brooks Macdonald

Canada Life

Candriam

Charles Stanley

Columbia Threadneedle

Credit Suisse

Deutsche Asset Management

Equitile

Evenlode

First Eagle Investment Management

Fisch Asset Management

Flossbach von Storch

Franklin Templeton

GAM

Generali Investments

Goldman Sachs Asset Management

Hermes

HSBC Global Asset Management

Insight Investment

Invesco**

Investec

Janus Henderson***

JO Hambro

JPMorgan Asset Management

Jupiter

Kempen Capital Management

Legal & General Investment Management

Lyxor

Man Group***

M&G Investments

Majedie Asset Management

Morgan Stanley

Natixis Global Asset Management****

NN Investment Partners

Newton Investment Management

Nordea

Northern Trust Asset Management

Old Mutual Global Investors

Pictet

Pimco

Rathbones

RBC

Robeco

Royal London

Ruffer

Russell Investments

Schroders***

Seven Investment Management

Standard Life Aberdeen

State Street Global Advisors

Stewart Investors/First State

SVM

T Rowe Price

Troy Asset Management

TwentyFour Asset Management

UBS

Unigestion

Union Investment***

Vanguard

Woodford Investment Management

* Previously said it would charge clients but changed course on December 15

** Had said preferred approach was to pass on research costs

*** Originally stated they would pass on research costs to investors

****Will absorb cost at majority of its European boutiques

*****Announced its decision on the day Mifid II regulations went live

Source: FT research

Paul Polman thought it was just going to be an informal catch-up. But it quickly became clear that Alexandre Behring, chairman of Kraft Heinz, had something very specific on his mind when he visited Unilever’s art deco headquarters in London last month.

Had Mr Polman, chief executive of Unilever since 2009, ever considered a collaboration with Kraft Heinz, Mr Behring wanted to know. Mr Polman took this as a sign of interest in Unilever’s spreads unit, home to brands such as Flora margarine, which his company considered “non-core”.

When he pressed Mr Behring for more details, the Brazilian businessman offered to return soon with a more thorough presentation. It was clear now to Mr Polman that this was no ordinary visit. He quickly assembled a small group, led by chief financial officer Graeme Pitkethly, to try to predict what the Kraft Heinz executives might be thinking.

The team began to consider what it viewed as the worst-case scenario: a takeover bid. Even though its US rival was far smaller than Unilever — a multinational corporation with annual sales of €52.7bn and 168,000 employees — Kraft Heinz could still afford a debt-fuelled acquisition of the Anglo-Dutch company.

The proposition was one to be taken seriously, given that 50 per cent of Kraft Heinz was owned by two formidable dealmakers, Warren Buffett and 3G Capital, the secretive private equity group that has been upending consumer industries from beer to fast food.

Mr Behring, a partner at 3G, returned to Unilever’s headquarters on February 10. Over sandwiches, Mr Behring laid out his audacious plan: Kraft Heinz would acquire its rival for $143bn, the second-largest takeover in history.

The cash-and-stock offer, which had the full backing of Mr Buffett and 3G’s founder Jorge Paulo Lemann, would create a global consumer powerhouse. Yet the proposal, to say nothing of the $50-a-share bid, which Mr Polman thought grossly undervalued his company, was appalling to the Dutch chief executive.

“The idea of being acquired appeared to blow his mind,” one person said about Mr Polman’s reaction to the offer.

Another insider said: “When they put something on the table, Paul was just utterly categorical that there was no merit. He gave a number of reasons why there was no interest in such an offer.” The offer was rejected immediately.

Mr Behring was surprised by Mr Polman’s unequivocal response. He thought their first meeting had gone well. This misreading would be the first in a series of mistakes that resulted in the bid’s collapse only nine days later.

When Kraft Heinz unexpectedly withdrew its bid on Sunday, it handed the first public defeat to a group of globetrotting investors who are not used to seeing their ambitions thwarted. The Financial Times interviewed more than a dozen people involved in the takeover battle to reveal how Unilever was able to beat back their offer.

A deal would have created the world’s second-largest consumer company by sales behind Nestlé. For the maker of Kraft Mac & Cheese and Heinz Tomato Ketchup, it would have more than tripled last year’s annual sales of $26.5bn and given the predominantly US-based group a deeper reach into emerging markets where Unilever dominates.

Polar opposites

From Mr Behring’s point of view, the timing was ideal. The 17 per cent slump in sterling since the UK voted to leave the EU in June meant he could buy some of the world’s most recognisable brands — from Dove soap to Ben & Jerry’s ice cream — in a once-in-a-lifetime sale.

For the Brazilian billionaires behind 3G, a Unilever acquisition would cap nearly 25 years of ever larger deals, including investments in beverages group Anheuser-Busch InBev and Restaurant Brands International, the owner of Burger King and Tim Hortons.

“The deal made perfect financial and strategic sense for them, but absolutely none for us,” says one person close to Unilever.

Kraft Heinz had misread Mr Polman, who likes to talk about managing growth for the longer term. By investing in its brands and promoting initiatives such as environmental sustainability, Mr Polman has sacrificed short-term profits for longevity.

In contrast, 3G has rapidly transformed the consumer industry by slashing costs, cutting jobs and raising profit margins. In a sector buffeted by slower growth and changing consumer habits, investors have cheered its austere management discipline, including a strategy known as zero-based budgeting. Rivals have recoiled at what they view as a model that ultimately destroys businesses by starving them of investment.

Yet some investors have questioned whether 3G’s tactics are too mercenary. Mr Buffett, who has built up a grandfatherly image as a hands-off acquirer and advocate of well-run companies, has faced criticism even from his own shareholders about 3G’s more ruthless approach to dealmaking.

“I tip my hat to what the 3G people have done,” he said in response to a question at Berkshire Hathaway’s 2015 annual meeting. He added that there were “considerably more people in the job than needed” at companies that 3G had bought. A combined 13,000 workers have been cut since Mr Buffett and 3G purchased HJ Heinz and merged it with Kraft Foods in 2015.

Still, 3G’s critics in the industry have been forced to respond to its aggressive management style — including Mr Polman, who last year outlined a three-year plan to boost profit margins and growth.

But 3G should have realised that Mr Polman would never fully embrace its philosophy. That would mean that Kraft Heinz may end up having to go hostile if it wanted to buy Unilever — a tactic Mr Buffett has vowed publicly that he would never use in his deals.

Kraft also miscalculated on another front: the changes sweeping the UK following the Brexit vote. Theresa May’s conservative government has become hypersensitive to the notion that British companies can be bought for knockdown prices due to the economic repercussions of the referendum.

A deal that could have also come with ruthless job cuts would encounter further political resistance — giving Mr Polman and his team another tool in their defence.

'Get them off the pitch early'

Mr Behring left Unilever’s offices with Mr Polman promising to get a full response from his company’s board after their next meeting, set to be held later this month. Mr Polman immediately called and hired Nick Reid and Robert Pruzan of Centerview Partners as his financial advisers.

Unilever’s team eventually grew to include Henry Stewart and Mark Rawlinson at Morgan Stanley, UBS, Deutsche Bank, law firm Linklaters and Tulchan Communications for public relations.

As the group studied the Kraft Heinz bid more closely it came to understand what the US company was attempting to pull off. The cost savings from combining with Unilever’s packaged foods business alone were enough to justify a big premium for the whole company, even though the unit was only 40 per cent of its sales. By that logic, Kraft Heinz would then be getting the rest of Unilever effectively for no premium.

The group studied 3G-backed takeovers and concluded Kraft Heinz would try to seem as friendly as possible and then increase its bid in increments until there was sufficient pressure from Unilever investors. This was 3G’s modus operandi. “We didn’t want to get in that situation, so we needed to hit them early. Our best chance was to get them off the pitch early,” said another person involved in the company’s defence.

They decided that Mr Polman should press ahead with a long-planned trip to Southeast Asia to not raise suspicions.

Because Kraft Heinz’s courtship was so young, secrecy became paramount to the success of its bid. But by last Wednesday, some investors and journalists had been notified about unusually high options trading in Unilever’s US-listed shares.

The next day, Kraft Heinz reported lacklustre quarterly results that investors saw as a sign that the company’s cost-cutting had reached a limit. Shares in the company sank 5.5 per cent.

Meanwhile, the Kraft Heinz board, which includes Mr Buffett, was holding a tense meeting. They feared that news of their bid was about to spill into the market, said two people briefed on the mood at that gathering. “The goal was to try to delay the leak as much as possible,” one of the people said.

By mid-morning on Friday, they were proved correct. The FT’s Alphaville blog revealed the details of the Kraft Heinz bid. Within half an hour, the US company confirmed it had “made a comprehensive proposal to Unilever about combining the two groups”. It added that the offer had been rejected but suggested that the door was still open.

Unilever slammed the door shut an hour later. In an unusually terse rejection, it said the Kraft Heinz offer “fundamentally undervalues” the company and that the proposal had “no merit, either financial or strategic”.

Kraft Heinz had expected its first offer to be rejected but was caught off guard by the harsh language Unilever used. “Everyone thought there was a relationship of mutual respect but clearly they went out strong on the culture stuff . . . making Kraft Heinz look like the bad guy and Unilever as the angel,” a person close to the US company said.

Kraft Heinz’s advisers at Lazard and law firm Paul Weiss, its top management and 3G executives regrouped later on Friday to find a new way forward. Additional advisers including PR companies Finsbury and Joele Frank were brought on. Shares in both companies soared to close the week. The US group was willing to pay substantially more.

However, more fissures appeared. UK politicians started voicing their concerns about another large British-based company being scooped up on the cheap by a foreign rival. Unilever could have ended up becoming the third major UK company to be acquired since the Brexit vote after chip designer ARM Holdings and pay-TV broadcaster Sky.

Under strain ahead of negotiations with the EU, the May government has further pigeonholed itself with its tough talk on a strong industrial policy that protected British companies and jobs. Shuttling between London and Paris to deal with the fallout of a proposed Peugeot-Vauxhall deal that could see thousands of jobs shed, Greg Clark, UK business secretary, spoke with Mr Behring and Sue Garrard, head of communications at Unilever.

Downing Street instructed officials to look at Unilever’s business in the UK and whether a Kraft Heinz bid would raise any policy issues, including over the future of the company’s British headquarters, its UK listing, jobs, and research and development.

Back in London on Saturday, as Mr Polman tapped into his network of contacts, he was informed that Finsbury was working with Kraft Heinz on PR. Within seconds, Mr Polman blasted off an email to Sir Martin Sorrell, the founder and chief executive of WPP, the advertising company that counts Unilever as one of its most important clients.

Finsbury, which is majority owned by WPP, was removed from the Kraft Heinz side by the end of the day.

'A surgical decision'

On Sunday morning in London, people close to Kraft Heinz said the US company was determined to make a series of concessions, including taking on Unilever’s name after the merger as well as offering guarantees to maintain R&D investments and headquarters in the Netherlands, UK and the US.

But Mr Behring, Mr Lemann and Mr Buffett received a letter from Mr Polman outlining his hostility to a deal. They decided then it would be better to retreat sooner rather than later. “It was a surgical decision,” said a person close to the trio. “There is little space for emotions in these circumstances.”

At 5:31pm a joint statement by Unilever and Kraft Heinz put to rest any hopes of a deal. It said: Kraft Heinz has the utmost respect for the culture, strategy and leadership of Unilever.

Although it would be foolish to rule out a 3G-inspired comeback of Kraft Heinz for Unilever, the Brazilian management cannot return for at least six months under UK takeover rules.

The ultimate decision to pull the plug on the effort was made by the two key billionaires backing the transaction — Messrs Buffett and Lemann, who wanted to avoid a potentially dirty and public takeover battle.

One person close to Unilever said: “From the lunch, Kraft Heinz should have got the impression that they had got it all wrong.”

Another says 3G and its portfolio companies have a clever way of doing business: “Extreme aggression with a smile, so we gave them extreme rejection with a smile.”

Undeterred by defeat, 3G’s Mr Lemann and his lieutenants are already planning their next move. A $15bn war chest is at their disposal, ready to hunt the next consumer goods monster.

A power struggle has broken out between Guggenheim Partners’ two most prominent executives, sapping morale, alarming clients and contributing to the departure of several top managers, according to current and former employees of the $240bn asset manager and investment bank.

The battle pitting founder Mark Walter against chief investment officer Scott Minerd has erupted at an inopportune time for the secretive but historically successful Wall Street firm, coming after it has seen a rare drop in asset management fees, according to documents seen by the Financial Times.

At least 10 senior professionals have left Guggenheim in the past 15 months, including co-head of corporate credit Jeff Abrams, macro strategist Anne Mathias and chief financial officer Brad Olson. Amid the upheaval, the firm recently added a new president of investment management and a new head of strategy and planning.

Guggenheim saw its total return to its owners drop by 4 per cent last year, while its investment management division reported a 5 per cent year-on-year drop in revenue to $765m, according to a June 30 memo sent to investors — an aberration at a group whose assets under management have grown from just $35bn 10 years ago.

According to employees and clients, the tensions between Mr Walter, Guggenheim’s chief executive and a co-owner of the Los Angeles Dodgers baseball team, and Mr Minerd, who has been credited with turning a small investment manager into a Wall Street powerhouse, were exacerbated by recent changes in the firm’s institutional distribution group, which acts as intermediary between Guggenheim’s money managers and investors such as pension funds, insurers and investment consultants.

Those clients include Midland National Life Insurance and the pension funds for the New York City Police and state employees in South Carolina.

Mr Minerd has been frustrated by changes implemented by Alexandra Court, an ally of Mr Walter’s, since she was promoted in April 2016 to be global head of institutional distribution, according to eight current and former Guggenheim employees.

Mr Minerd “is frustrated with the choices and decisions of certain executives and their impact on the direction, culture and soul of the firm as it has grown,” according to a person close to him, who added that Mr Minerd would not provide comment to the FT

Mr Walter, an Iowa native, co-founded privately held Guggenheim in 1999, combining his small Chicago investment firm with a family office that managed a portion of the Guggenheim fortune that traces back to 19th century lead and silver mines. Mr Minerd, a competitive bodybuilder who joined Guggenheim at the start, is the face of the business, appearing frequently on television and in print to discuss global economic and investing themes.

Within days of Ms Court’s appointment last year, 22 members of the US distribution team she took over were fired, saving about $10m in annual costs but angering several of Mr Minerd’s investment colleagues. The firm also changed the structure of the distribution team, sharply reducing the number of employees handling calls and requests from institutional clients.

Guggenheim’s money managers were barred from communicating directly with clients unless interactions were arranged through Ms Court’s sales team, according to a January 2017 memorandum sent to the investment team by Mr Walter and Andrew Rosenfield, a managing partner. The memo, seen by the FT, cited “a fundamental change” when Ms Court was appointed.

“Only Distribution has the authority to schedule meetings, to prospect and to manage client services,” the memo read. “Consistent with this, [portfolio managers] were instructed that they were, under no circumstances, themselves to set up prospecting meetings, to market funds or services, to schedule client meetings or to deal directly with clients at all unless authorised, in advance, by Distribution to do so.”

Although a spokesman for Guggenheim said Ms Court was selected by a group of company executives including Mr Minerd, the people close to Mr Minerd said she was selected only after two other internal candidates he preferred were passed over.

Mr Minerd and his team believe Ms Court was emboldened to implement changes due to a close relationship she had with Mr Walter, according to 11 current and former employees at Guggenheim. A spokesman for Guggenheim disputed this, saying she did not report directly or indirectly to Mr Walter and her restructuring was part of a strategy approved by the division’s entire leadership.

Mr Walter’s relationship with Ms Court was disclosed to the members of Guggenheim’s board, according to three executives.

The Guggenheim spokesman said: “There is no non-business relationship, but if there were it was fully and promptly disclosed to the appropriate parties at Guggenheim in accordance with established processes and procedures, which were then fully implemented, to avoid improper influence or favour.”

Mr Minerd’s allies said the investment chief is not interested in replacing Mr Walter as chief executive, but the upheaval inside the firm was leading him to question Mr Walter’s position.

The Guggenheim spokesman denied any split between Mr Walter and Mr Minerd, insisting recent tensions were “nothing more than the usual internal debate.” In an email the spokesman added: “If people perceive the interaction between the two of them as a power struggle, we believe that is an inaccurate portrayal.”

Ms Court has strongly defended her role at the firm, citing her prior record as London-based head of distribution in Europe where she successfully ran a much smaller team than Guggenheim had in the US, a streamlined model that her American team has now also pursued.

“The Institutional Distribution team services and maintains in excess of 800 clients and client retention has been close to (if not) 100 per cent since my appointment,” Ms Court said in an email.

Assets under management have grown by more than $20bn since her appointment, according to the company, and while Guggenheim reported a decline in revenues in its June memo to investors, it also said performance in the first half of 2017 led it to expect a return to growth in the full year.

Guggenheim employees own about 45 per cent of the company, according to its website. Sammons Enterprises, Guggenheim’s largest outside shareholder and a big investor in its funds, declined to comment.

However, Mr Minerd and several other senior Guggenheim portfolio managers believe the cuts to Ms Court’s US team are hampering the firm’s ability to raise new money from institutional investors, according to more than 10 current and former employees.

“We didn’t have an outlet to distribute investment capabilities,” said one current Guggenheim fund manager, pointing to the inability of portfolio managers to contact clients directly. “Clients have been negatively impacted.”

Two investment consultants, who recommend clients to Guggenheim, said they had seen a marked drop-off in responsiveness from the firm after Ms Court’s promotion and the subsequent upheaval.

“The turnover [of staff] is causing concerns about what else is going on over there. We are increasing our scepticism,” said one consultant, who asked not to be named.

Another said: “We used to have a dedicated person on our account before Alex Court joined. After that, there was only a single person to cover all their accounts. We had to find other people at Guggenheim outside [her] group to handle our requests.”

Ms Court has insisted that two members of her team are allocated to each account, ensuring timely responsiveness.

Mr Minerd’s team is unhappy with the new role for Ms Court’s distribution team, in part, because they believe the chief investment strategist is responsible for the group’s strong performance and should be treated as one of the leading figures on Wall Street.

“Bill Gross and Jeff Gundlach are Scott’s [Minerd] peers but those guys are actually running their firms. Scott’s frustration is not knowing where the firm is going,” another person close to Mr Minerd said.

Some Guggenheim staff members have also raised concerns about Ms Court’s lack of US securities licences. At most of Guggenheim’s direct competitors — such as Lazard, Voya, Barings, TWC and Janus Capital — the heads of distribution have a series 7 or series 24 certification issued by Wall Street’s self-regulatory body, Finra. These licences, which are obtained by passing exams, are considered to be standard for professionals marketing financial products and supervising other sales executives, respectively.

The Guggenheim spokesman, Michael Sitrick, said the firm had sought a waiver from the licensing requirement from Finra when Ms Court moved from the UK, where she had similar Financial Conduct Authority licences, but Finra denied the request in the middle of last year. Mr Sitrick added that at all times appropriately licensed professionals have overseen all of the firm’s distribution staff.

In June, Guggenheim notified staff that Ms Court had taken a summer sabbatical and would return on September 1, according to an internal memorandum seen by the FT. Guggenheim’s spokesman said Ms Court would have licences when she returns.

Consultants who work with Guggenheim say they hope the firm will sort out its infighting. “We think the investment team at Guggenheim has a truly differentiated product. We think highly of them. We hope there is chance that things improve over there now,” one said.

All change at asset manager

While Alexandra Court is on sabbatical until September 1, when she is due to return to her role as head of global institutional distribution at Guggenheim Partners’ investment arm, several big changes have occurred within the Wall Street asset manager.

Jerry Miller, a former Deutsche Bank executive who has been serving as a consultant during Ms Court’s absence, has been named Guggenheim Investments’ new president. Dina DiLorenzo, a Guggenheim veteran, was at the same time appointed chief operating officer of the division.

In recent months, there have also been several key departures from the company. These include portfolio managers, Jeff Abrams, co-head of corporate credit, and Brendan Beer, co-head of structured credit who moved to Oaktree Capital. Brad Olson left his job as Guggenheim’s chief financial officer for a tech start-up and macro strategist Anne Mathias left to join Vanguard.

Penny Zuckerwise, a previous head of global distribution, has also resigned from her most recent position as head of corporate social responsibility. Multiple people familiar with the company say a particularly difficult situation involves Frank Beardsley. Mr Beardsley, a senior managing director, is the primary conduit between the company and its crucial insurance clients but has been negotiating his departure. However, a Guggenheim spokesperson states that Mr Beardsley is still an employee and is not leaving.*

In late 2016, Guggenheim hired David Rone as the company-wide head of strategy. Mr Rone, who had no direct investment management experience, most recently was an executive at Time Warner Cable Sports where he worked with Guggenheim founder Mark Walter, a co-owner of the Los Angeles Dodgers.

This article has been amended to reflect that Frank Beardsley has not left the firm as originally reported

For several months, the identity of a mystery buyer of millions of dollars of insurance against financial meltdown has consumed Wall Street traders.

The investor, who has been regularly sweeping into an obscure corner of the derivatives market and purchasing contracts priced at half a dollar, has been dubbed “50 Cent” after the US rapper known for his album Get Rich or Die Tryin’.

Several bankers and traders familiar with the trades believe that the buyer lies far from the streets of lower Manhattan.

Instead, they point to a UK investment firm just a few minutes’ walk from Buckingham Palace in London whose co-founder has donated some of his fortune to restoring a castle in the north of England.

Ruffer, a $20bn investment fund co-founded by Jonathan Ruffer with clients including the Church of England, has been systematically buying up derivative contracts linked to an index known as the Vix, according to four people from trading departments at banks who are familiar with the trades. Those contracts would pay out if volatility jumps, as it could in the event of a large drop in the US stock market.

The trades come as US stocks set new records in a nine-year bull market that some believe is ripe for a correction. In his most recent letter to investors, Mr Ruffer cautioned that “markets, especially in the US, are once again exceedingly expensive”.

Ruffer declined to comment on the trades, or whether it is the investor known as “50 Cent”.

However, in an investment presentation last year, Ruffer said that it had been purchasing volatility protection. “We regard them as necessary for the scenario we most fear: a major correction in both bond and equity markets.”

Analysts say the hedging strategy is a prudent piece of risk management, but could prove costly if volatility remains subdued.

The CBOE’s Vix “fear index” fell to its lowest level since early 2007 this week, with investors betting on a more measured geopolitical environment amid polls showing centrist Emmanuel Macron the favourite to be elected French president on Sunday. So far, $88m of the $120m in option premium spent by “50 Cent” this year has expired worthless.

Ruffer’s strategy involves buying contracts that become profitable should the Vix, a measure of implied volatility in the benchmark S&P 500, rise significantly, those familiar with the trades say.

The investment fund’s strike prices are mostly around a Vix level of 20, a threshold that has been breached only three times since the start of 2016. This week, the index slipped below 10.

The $120m spent by “50 Cent” accounts for about 8.5 per cent of the open interest in Vix call options that are listed or exchange traded, according to analysis from Pravit Chintawongvanich, head of derivatives strategy at Macro Risk Advisors.

“It is a very big position,” Mr Chintawongvanich said.

Analysts and traders in the Vix options market have concluded that “50 Cent” is likely to be just one investor because the pattern of buying options that always cost near $0.50 is unusual.

Other asset managers use Vix calls in similar volumes as hedges against market disruption, but their trading activity is less systematic and leaves less obvious traces.

The ranks of investment bank research analysts have fallen by one-tenth since 2012, as tighter regulation and falling profits have forced financial institutions to cull their brigades of economists, bond strategists and stock pickers.

The number of analysts working at the world’s 12 biggest investment banks fell to 5,981 last year, according to fresh numbers from Coalition, a data provider on the industry. That is down from 6,282 at the end of 2015, and 6,634 at the end of 2012, when Coalition began to collect the numbers.

The cuts are expected to deepen in the coming years. “We will have massive cost pressures in an industry that is not ready for it at all,” said Matthew Benkendorf, chief investment officer at Vontobel Asset Management. “They’ll have to gut things pretty hard.”

The profitability of “sellside” research has been eroding ever since dotcom bust, when allegations of biased research led to tighter use on the rules around using analysts to drum up investment banking business. Then, after the financial crisis, newly cost-conscious banks started slashing staffing of research departments, because they made little direct contribution to earnings.

Incoming EU regulations are expected to deepen the research cull, because money managers that operate in the region will be required to pay banks directly for any research they consume. Currently, research is largely funded through commissions on trades. Some asset managers are therefore bulking up their own analysis departments and many plan to cut spending on outside research.

While these new regulations only apply in the EU, many of the bigger US asset managers are likely to follow the same path. A survey of 30 global investment groups and investment banks by Quinlan & Associates last year indicated that research budgets would be cut by 30 per cent.

“It’s going to get worse before it gets better,” said George Kuznetsov, head of research at Coalition. “There is a lot of overcapacity that will be resolved in the coming years.”

Coalition collates its data from scraping the names on research reports published by many of the biggest banks, such as JPMorgan, Deutsche Bank, Barclays, Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley and HSBC, but many smaller brokerages have also made substantial cuts.

For example, David Ader and Ian Lyngen were earlier this year voted the top US Treasury analyst team in Institutional Investor’s prestigious poll for the 11th year running, but at the time both were unemployed as CRT Capital Group, their company, was in the process of being shuttered.

“It’s a different game today and folks like us may be valued by you readers but are a cost,” Mr Ader wrote in his farewell email to clients.

“If I ever again hear the question ‘how do we monetise you?’ applied to our work I think I’ll go back to bong hits and not worry about drug tests in the next job . . . if there is a next job.”

Since then, Mr Lyngen has found a job at BMO Capital Markets and Mr Ader at Informa Globalmarkets. But many of their former colleagues and counterparts have been less lucky.

David Ader was standing in the middle of the North Platte river in Wyoming, trying to land a rainbow trout that had gobbled his hook, when his phone rang with a message that he had just been voted America’s top government bond analyst for the 11th year in a row. Unfortunately he was unemployed at the time.

His former employer, a midsized New York brokerage called CRT Capital, had been forced to shut its doors just weeks before Mr Ader won the prestigious Institutional Investor gong together with his long-time sidekick Ian Lyngen in October. It naturally tempered their triumph.

The strategists lost their jobs because of CRT’s woes, but the closure was indicative of broader challenges afflicting the investment research industry. Mr Ader’s farewell email joked that if anyone asked him how to monetise their work again he would “go back to bong hits” rather than worry about the next job — if he ever found another one.

Both strategists soon found new employment, but the joke reflected a broad and profound frustration in the research industry. “The term ‘monetisation’ comes up all the time. It’s challenging always having to justify your existence,” Mr Ader says. “The changes I’ve seen in the industry are frustrating and disappointing. It’s not much fun any more.”

Slashed budgets

Over decades banks and brokerages have assembled armies of analysts to decipher central bank speeches, parsing the entrails of the bond market, sifting through corporate balance sheets and guessing where copper prices or the Turkish lira are heading. Research served both as external marketing and as fodder for the bank’s own traders, and the best analysts were accorded rock star status in the finance industry. But the investment research business is now in crisis.

Sellside research

%16bn Total annual budget for analyst research, according to BCA

>40,000 Pieces of research emailed every week by the bigger banks and brokerages, according to Quinlan & Associates

2-5% Of research emails are read each week, according to industry insiders

30% Global asset managers plan to slash their research budgets by a third, according to Quinlan & Associates

Banks are under pressure to cut costs, and while analysts cost less than a star trader or M&A rainmaker, their contributions to profits are more ephemeral. Stricter regulations imposed after the dotcom crisis in 2000 curtailed their ability to directly drum up business. And the sheer number of “sellside” economists, analysts and strategists means a lot of work is duplicated and goes unread, especially as many “buyside” asset managers are building up their own internal research teams.

New EU rules, due to come into effect in 2018, will force asset managers to pay directly for research, rather than do so surreptitiously by pushing business to the banks whose analysts they like. While this will only affect Europe, most participants expect it to have a significant knock-on impact on the global research industry.

BCA, an independent analysis group, estimates that the global investment research spend is roughly $16bn annually, but that is expected to shrink drastically in the coming years. A recent poll of asset managers by consultants Quinlan & Associates indicated they plan to slash their research budgets by 30 per cent. Although the cuts will be heaviest in Europe, no region will be spared.

These forces have plunged the investment research industry into a similar debate to the one raging in the media sector: how to add value; how to get noticed; and how to monetise the content. Getting it right matters, because research is still an important cog of global markets and the real economy, helping direct capital to where it can be most effective.

But even with a successful transition to a more technology-oriented, big data-driven model, an extensive cull looks inevitable. The number of analysts at the 12 biggest banks has already slid by 10 per cent since 2012 to 5,981 in 2016, according to Coalition, a data provider, and worse is to come, predicts Henry Kaufman, the first economist to earn the sobriquet Dr Doom for correctly predicting in the 1970s that interest rates would rise aggressively to batter inflation. “There will be a diminution of numbers,” he warns. “It won’t be an easy process of adjustment.”

The Kodak effect

In 2013, Bashar al-Rehany, the chief executive of BCA Research in Canada, assembled his entire team of analysts and executives at the Omni hotel in downtown Montreal. Together with a group of invited technologists and data scientists they tried to chart a new future for the business.

BCA is one of the oldest and biggest of the standalone investment research groups unaffiliated with a major bank or brokerage, along with the likes of the UK’s Lombard Street Research, Evercore ISI on Wall Street and Hong Kong’s Gavekal. But Mr Rehany is uneasy about the future at a tumultuous time for the industry.

“I don’t want to end up like Kodak,” he says of the company that failed to realise, until it was too late, the impact of digital photography on its business. He is therefore transforming BCA into something closer to a high-end digital publisher, moving away from distributing static, long-winded reports by email and instead nudging clients towards an interactive website that deconstructs research into individual components.

“We break down the report into individual Lego blocks, so people can get what they want, and can build it up in the way that fits their consumption pattern,” says Brijesh Malkan, who leads the BCA Edge project. Thus far it has been a success, with migrated clients consuming as much as 20-30 per cent more of BCA’s research.

BCA is not alone in trying to chart a more digital future. Virtually every investment bank now embeds cookies that monitor how many of their emails get opened, how many PDFs get downloaded and how much of a report actually gets read. Many push clients to their website for better monitoring and to encourage more engagement with catchy headlines. Some even include social media-style “like” buttons.

Despite the recent spate of analyst job cuts, asset managers still face an avalanche of research reports tumbling into their email every day. Benjamin Quinlan, chief executive of Quinlan & Associates, estimates that even excluding the independent research boutiques, banks and brokerages send out more than 40,000 articles a week.

Yet the amount of research actually consumed is depressingly low, with some industry insiders estimating that only between 2 per cent and 5 per cent of all reports produced are actually read.

Juan-Luis Perez, head of global research at UBS, blames the industry’s lack of innovation, arguing that the fundamental approach has not changed much in the past century.

“If I showed you a report from the 1920s and today you’d be surprised at how similar they are,” he says.

Ending cosy relationships

Some money managers say they no longer care about research and are more interested in access to the corporate executives and country officials that analysts cover. Compensation is often tied to how many meetings analysts can arrange, but this encourages them to soften reports to maintain access.

Regulators take a dim view of this. Last year the Securities and Exchange Commission censured a former Deutsche Bank analyst for assigning a “buy” rating on Big Lots Stores purely to maintain his relationship with the company. Senior analysts argue that the industry will have to evolve beyond being a glorified chaperone service.

Mr Perez, poached from Morgan Stanley in 2013, has overhauled how UBS produces research. He has hired data scientists, computer coders and even psychologists to run an “Evidence Lab” and work in conjunction with industry specialists to answer client research inquiries submitted to the Swiss bank. Reports are interactive so clients can plug in their own assumptions for variables such as economic growth or a company’s widget sales. “Research will have to clear a higher bar,” Mr Perez says. “The future will be integrating big data, high-end statistical research and traditional analysis.”

Several banks are even working on “virtual” analysts, sophisticated software powered by artificial intelligence techniques like machine learning and natural language processing, which could automate a lot of the more menial tasks and ultimately even render lower-level analysts obsolete.

Yet even with more innovation, the economics of sellside research will remain challenging. Money managers have historically rewarded banks and brokerages with research they liked with trading business, which often came with fat commissions. Nowadays, electronic markets coupled with regulatory requirements for asset managers to always seek the best-possible execution have frayed this “bundled” approach.

“The big traders are algorithms these days,” Mr Ader points out. “It has become an Amazon-style world where you can just buy a stock or a bond electronically. That’s great for clients, but it’s a huge, huge change for the research business.”

Investor alternatives

The evolution towards unbundling research from trading commissions will be accelerated by a batch of incoming EU legislation called Mifid II. The second Markets in Financial Instruments Directive will force investment groups to split out payment from research, either covering the cost themselves or passing it on overtly to clients. As it is hard for asset managers to disentangle European operations from a global business, some investment managers will in practice apply the standards across their operations.

Asset managers are also coming under pressure from passive alternatives like index-tracking and exchange traded funds. Last year more than $1bn a day flowed from active managers to passive funds, ramping up the incentives for investment groups to cut costs.

Independent research boutiques will be the winners from Mifid II, as they will be able to compete more directly with banks for an investment firm’s dollars. But the combination of cost-cutting and regulations is pushing many investment groups to build up their own in-house analysis teams.

In response to the new rules, 38 per cent of fund managers polled by the Edinburgh-based Electronic Research Interchange said they will expand their internal research teams rather than relying on traditional sellside analysts. Many of the biggest investment houses have already started.

“We felt the need to build up our own capacity because of a diminution of the quality of the sellside research,” says David Hunt, chief executive of PGIM, Prudential’s $1tn asset manager. “It’s been a big shift. We’ve taken on a lot of costs, but net-net it’s good. The quality of our information has gone up.”

Despite sometimes flippant comments on the value of sellside analysts, most investors will still need research in the future. But what it looks like, who produces it and how it is distributed is likely to change dramatically.

Mr Ader quickly landed a job as Informa Financial Intelligence’s chief macro strategist in the research group after CRT shuttered, but he is not optimistic on the future of his industry.

“It’s always darkest before dawn, so maybe we can come back. But for a long time, perhaps forever, the nature of analysis will change. It will become even more computer-based,” he says. “There will always be a need for humans to look at the big picture and explain markets, but it will certainly be more limited in the future.

The FT’s Opinion page is the must-read forum for global debate

on economics, finance, business and geopolitics.

Financial Times commentators are sharp, lively and sometimes controversial. You may not always agree with their

views – indeed, they do not always agree with each other. But you will find their observations both thoughtful

and thought-provoking, giving you penetrating new insights each day.

Chief economics commentator Martin Wolf is as informative on terrorism as on tax policy, while Gideon Rachman

offers forthright comment on foreign affairs. Gillian Tett illuminates the latest developments in the markets,

John Gapper gives you fresh insights into business trends and strategy and Merryn Somerset Webb writes a penetrating

weekly column on investing and personal finance. You will also find many other specialists, on topics from

politics to Asia to investment.

Many of the world’s most powerful people not only read the FT – they write for it, too. Our guest contributors

have ranged from Tony Blair and Bill Gates to Madeleine Albright and Kofi Annan. They will give you a fascinating

insight into the world through the eyes of the people who shape it.

Merryn Somerset Webb

Editor in Chief of MoneyWeek

‘A canny commentator on personal finance who tells it like it is – with a smile’

Merryn Somerset Webb is the editor in chief of MoneyWeek.

After gaining a first class degree in history & economics at Cambridge, Merryn became a Daiwa scholar and spent a year studying Japanese at London University. In 1992, she moved to Japan to continue her Japanese studies and to produce business programmes for NHK, Japan’s public TV station.

In 1993, she became an institutional broker for SBC Warburg, where she stayed for 5 years. Returning to the UK in 1998, Merryn became a financial writer for The Week. Two years later, in 2000, MoneyWeek was launched and Merryn took the job of editor.

Gideon Rachman

Associate Editor and Chief Foreign Affairs Columnist

‘Irreverent and original columnist on global affairs’

Gideon Rachman became chief foreign affairs columnist for the Financial Times in July 2006. He joined the FT after a 15-year career at The Economist, which included spells as a foreign correspondent in Brussels, Washington and blockchain.

He also edited The Economist’s business and Asia sections. His particular interests include American foreign policy, the European Union and globalisation.

Martin Wolf

Chief Economics Commentator

‘Brilliant author, economist. Must-read for central bankers’

Martin Wolf is chief economics commentator at the Financial Times, London. He was awarded the CBE (Commander of the British Empire) in 2000 “for services to financial journalism”. Mr Wolf is an honorary fellow of Nuffield College, Oxford, honorary fellow of Corpus Christi College, Oxford University, an honorary fellow of the Oxford Institute for Economic Policy (Oxonia) and an honorary professor at the University of Nottingham.

He has been a forum fellow at the annual meeting of the World Economic Forum in Davos since 1999 and a member of its International Media Council since 2006. He was made a Doctor of Letters, honoris causa, by Nottingham University in July 2006. He was made a Doctor of Science (Economics) of London University, honoris causa, by the London School of Economics in December 2006. He was a member of the UK government's Independent Commission on Banking in 2010-2011. Martin's most recent publications are Why Globalization Works and Fixing Global Finance.

Gillian Tett

US Managing Editor and Columnist

‘Renowned for her coverage of credit risk ahead of the global financial crisis’

Gillian Tett serves as US managing editor. She writes weekly columns for the Financial Times, covering a range of economic, financial, political and social issues.

In 2014, she was named Columnist of the Year in the British Press Awards and was the first recipient of the Royal Anthropological Institute Marsh Award. Her other honors include a SABEW Award for best feature article (2012), President’s Medal by the British Academy (2011), being recognized as Journalist of the Year (2009) and Business Journalist of the Year (2008) by the British Press Awards, and as Senior Financial Journalist of the Year (2007) by the Wincott Awards. In June 2009 her book Fool’s Gold won Financial Book of the Year at the inaugural Spear’s Book Awards.

Tett’s past roles at the FT have included US managing editor (2010-2012), assistant editor, capital markets editor, deputy editor of the Lex column, Tokyo bureau chief, and a reporter in Russia and Brussels. Her upcoming book, to be published by Simon & Schuster in 2015, will look at the global economy and financial system through the lens of cultural anthropology.

John Gapper

Chief Business Columnist and Associate Editor

‘Original observer of the media and tech scene who writes with elegance and wit’

John Gapper is associate editor and chief business commentator of the Financial Times. He writes a weekly column, appearing on Thursdays on the Comment page, about business trends and strategy. He also contributes leaders and other articles.

He has worked for the FT since 1987, covering labour relations, banking and the media. In 1991-92, he was a Harkness fellow of the Commonwealth Fund of New York, and studied US education and training at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania.

A decade ago, I spent a sleepless night worrying about a Spanish trash bin. The reason? On Thursday August 9 2007, financial markets suddenly seized up.

Since I was running the Financial Times markets team, I spent two days frantically trying to identify the reason for the panic. Nobody knew. But that weekend I suddenly woke in the middle of the night with an image of a Spanish bin in my head.

A month earlier I had attended a credit conference in Barcelona, where I read brochures about a little-known, and supposedly safe, entity known as a “structured investment vehicle”. The material had seemed achingly dull. So on the way home I tossed the papers into an airport bin — and forgot it. But, somehow, my subconscious knew that had been a mistake. So I awoke and went online to uncover what I had left in that bin.

By dawn I had realised that those widely ignored investment products were a key culprit in the market mystery: the details were complex, but essentially these SIVs held toxic mortgages and were plagued with dangerous asset-liability mismatches that had caused investors to panic.

There is a lesson in this tiny piece of personal history, as we look back from the 10th anniversary of the drama to assess what happened — and not just to observe that our brains can work in mysterious ways.

Sometimes, market shocks occur because investors have taken obviously risky bets — just look at the tech bubble in 2001. But other crises do not involve risk-seeking hedge funds, or products that are evidently dangerous. Instead, there is a ticking time bomb that is hidden in plain sight, in corners of the financial system that seem so dull, safe or technically complex that we tend not to focus attention on them.

In the 1987 stock market crash, for example, the time bomb was the proliferation of so-called portfolio insurance strategies — a product that was supposed to be boring because it appeared to protect investors against losses. In the 1994 bond market shock, the shocks were caused by interest rate swaps, which had previously been ignored because they were (then) considered geeky.